Chapter IV

From Network-Source AI to Broad Listening

Chapter Summary

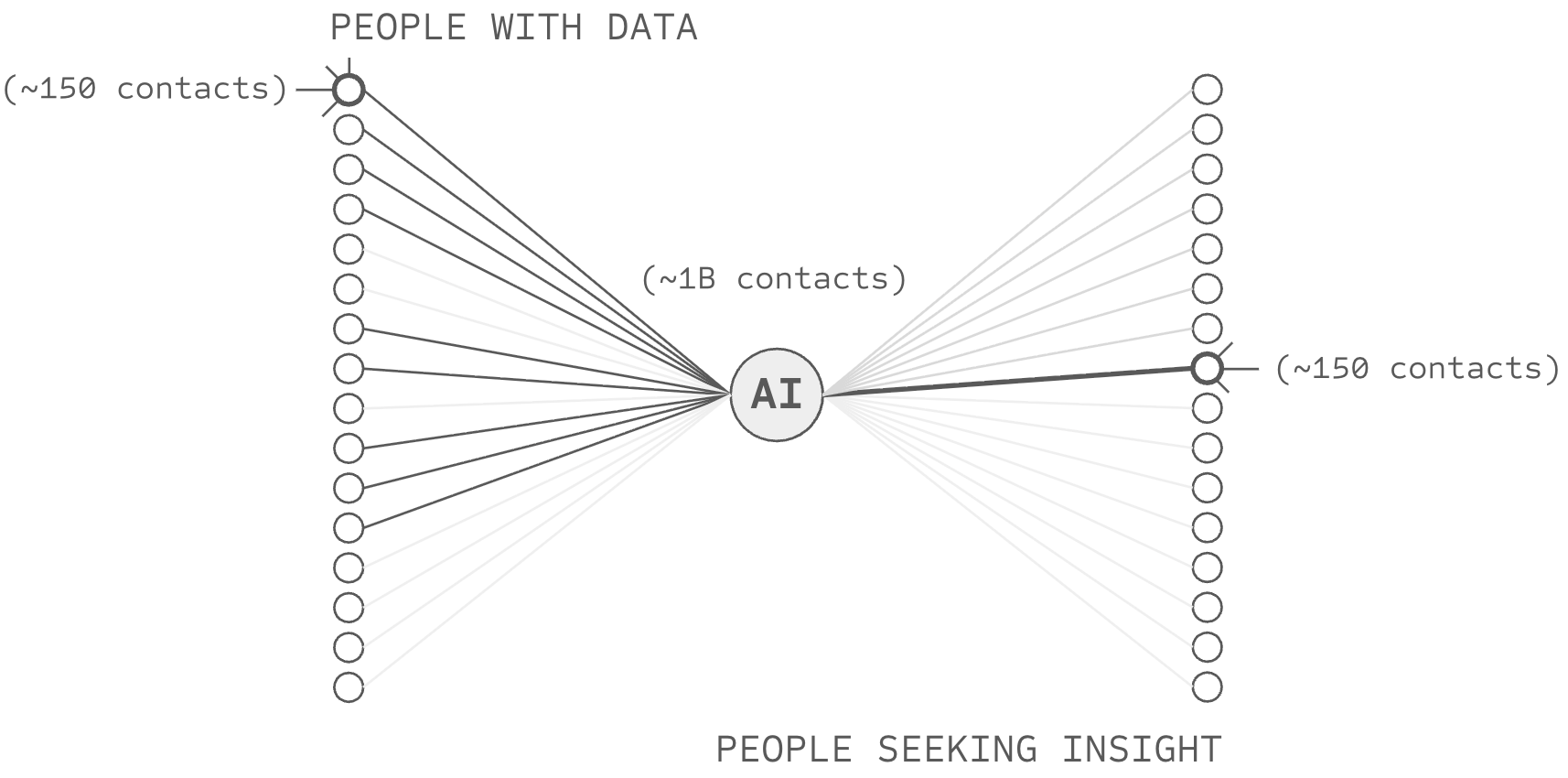

Chapters 2 and 3 developed the technical machinery to deliver ABC, but a close reading will surface that the machinery has a flaw which must be addressed: trust at scale. As individuals, AI users and data sources can evaluate perhaps 150 counter-parties by cultivating strong-tie relationships with them. Yet, owing to scaling laws, NSAI requires evaluating millions of data sources in order to curate as much data as standard AI systems.

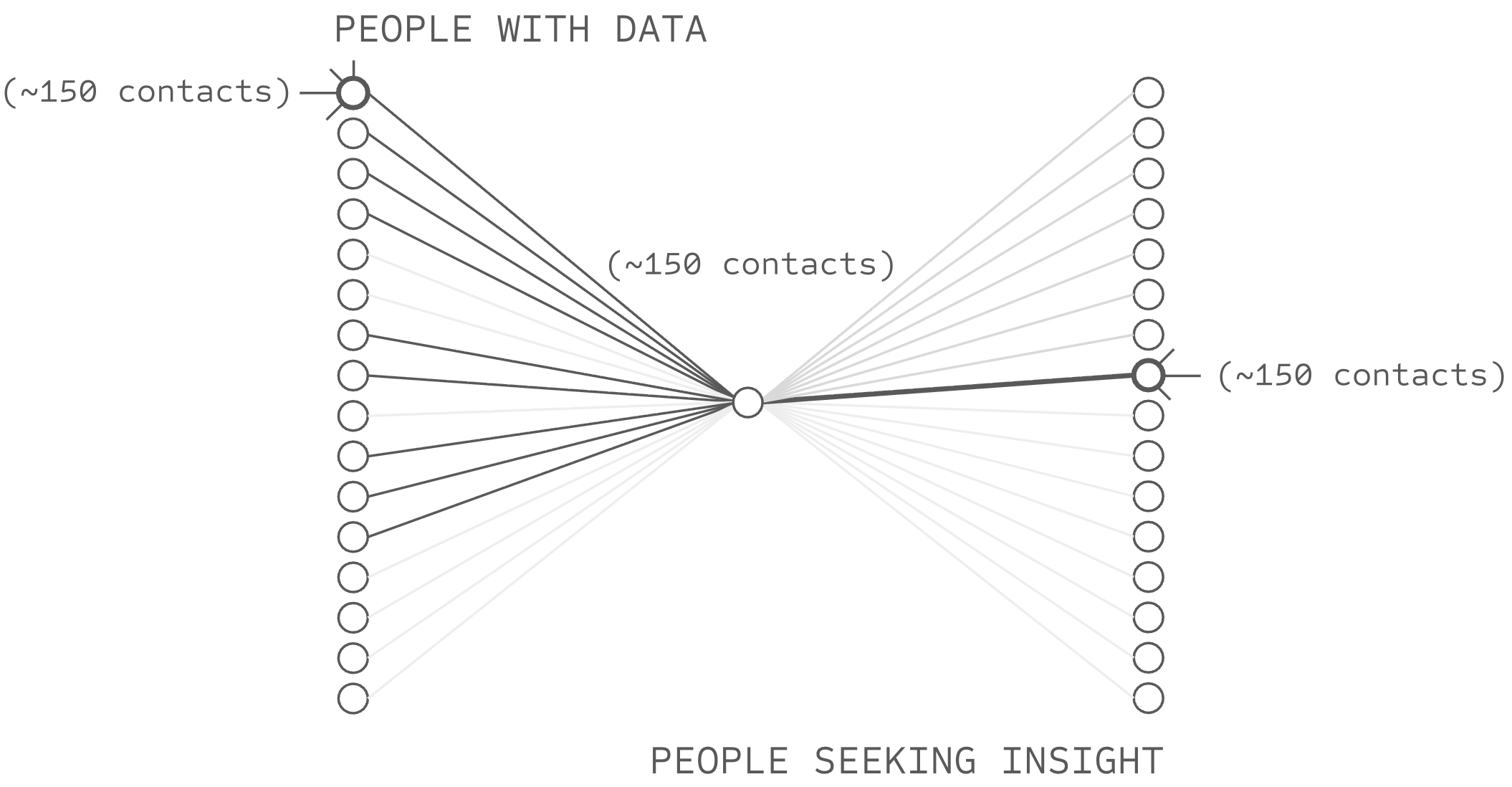

Delegation of trust evaluation is therefore necessary, but it too has a fatal flaw: if AI users and data sources delegate trust evaluation to a small collection of central parties, NSAI collapses back into the system it was meant to replace. This chapter identifies the root issue as high-branching nodes; any node connecting to millions cannot cultivate the strong-tie relationships that trust evaluation requires. The chapter then prescribes recursive delegation through low-branching networks as the remedy, yielding a new paradigm: broad listening.

The Problem of ABC in Network-source AI

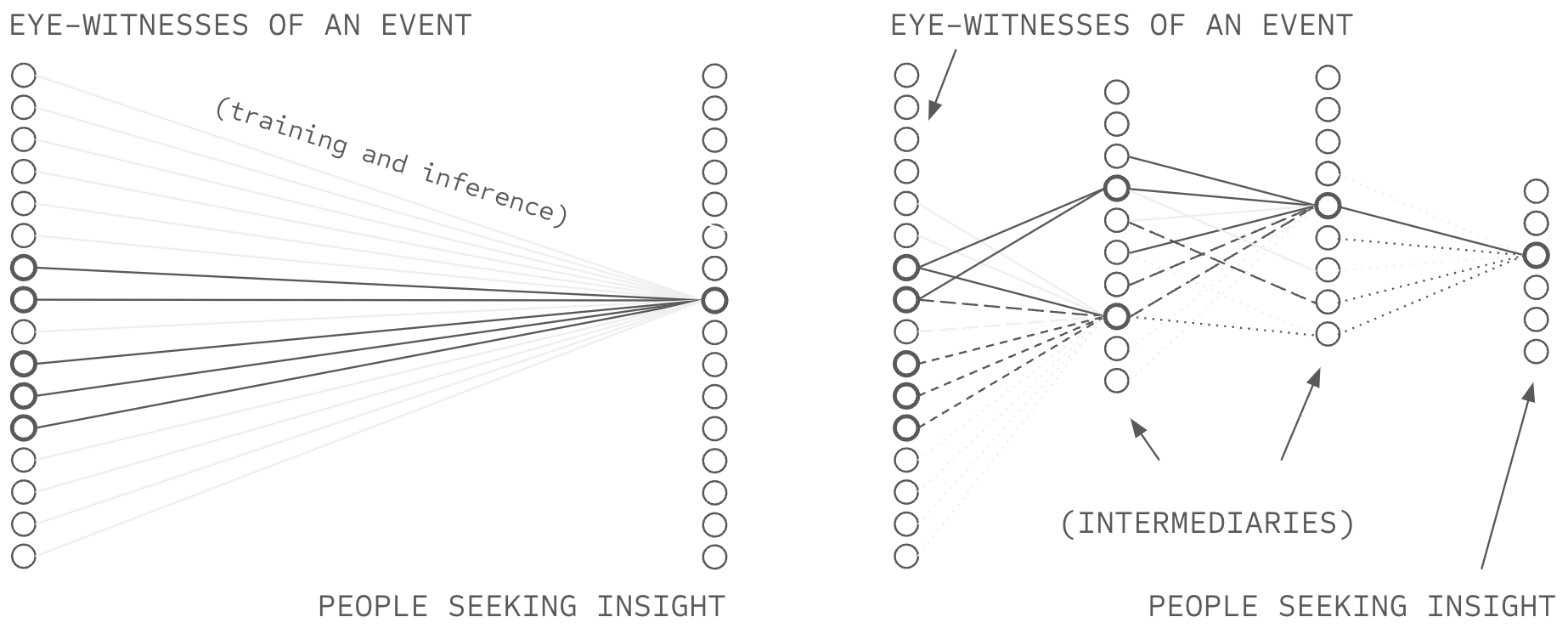

Standard AI is trained on a curated dataset and can only leverage information obtained by the AI owning entity to make predictions. In this way, standard AI is like a rudimentary, button-less, hot-line telephone where users can only call the telephone provider for information, and the telephone provider can only reply based on information they have gathered. Network-source AI (NSAI) is like a modern telephone, giving users the ability to dial anyone in the world directly, circumventing the data collection processes and opinions of the telephone provider.

But while NSAI offers a technical capability for ABC, a subtle problem undermines it in practice: the ability to dial is not the same as knowing whom to call, and the ability to reply is not the same as knowing who to support with AI capability. Deep voting aggregates contributions according to trust weights (the intelligence budget), and structured transparency protects those weights, but neither chapter specifies where the weights come from. The system is incomplete in precisely the way a combustion engine is incomplete without fuel: the machinery is specified, but the input that makes it run is not.

The Diagnosis

Let's say you receive a problematic test and need an oncologist to follow up. Using your phone, you can theoretically dial any oncologist on earth, but your phone contains near-zero oncologists whose judgment you have personally evaluated. Let's say your city has hundreds of oncologists, your country has tens of thousands, and in theory you could contact them one by one. Each would probably answer, but each answer would contain what the oncologist chooses to share, something like "yes I'm a great doctor... what is your insurance and when can you come in for an evaluation?"

In a way... the oncologist is not really who you want to call. You want to call the patients, people who trusted each oncologist with their life and learned whether that trust was warranted. The patients have information beyond what the typical oncologist is likely to disclose, such as whether the doctor listens, whether they rush, whether their diagnoses prove correct, and whether their patients are cured.

However, you cannot collectively dial all the patients of the world's oncologists; even if you had a team of people to help you make thousands of phone calls, you do not know the names or numbers of each oncologist's patients. They are not listed anywhere you can find. Some of them are almost certainly friends of friends of friends of yours... so the path to an introduction might exist... but you cannot see or traverse it. Indeed, the information is almost certainly there.

But you have no way to ask.

First Why: Why Individuals Cannot Evaluate at Scale

Trust requires observation. If no one has ever observed a party perform, no one can trust that party to perform well, one can only hope. One might be tempted to argue that everyday life involves trusting many people one has not directly observed (e.g., taxi drivers, baristas) because they are credentialed in some way. But credentials, ratings, and recommendations do not create trust; they transfer it. At the origin of every trust chain, someone watched.

Consider the CV of the oncologist from the example above. It represents layers of transferred trust from medical schools that observed her learn, residency programs that observed her practice, and credentialing boards that reviewed her record. Patients who trust the CV are trusting these institutions to have done the observation on their behalf. But after treatment, successful patients hold something stronger: trust built through their own time with her, perhaps through diagnoses that proved correct or through her listening when they were afraid. While the CV offers borrowed trust, the relationship offers earned trust.

Sociologists call these high-trust relationships "strong ties": relationships characterized by sustained interaction, emotional investment, and mutual obligation. The last element is crucial. Mutual obligation means both parties have stakes in the relationship's continuation... and therefore both bear costs if they betray it. This is what makes strong-tie trust enforceable rather than merely hopeful.

The problem is that building strong-tie relationships requires attention, and attention is finite. Dunbar's research establishes the constraint as universal across humans: approximately 150 stable relationships... a limit traced to neocortex size itself.

Meanwhile, NSAI requires trust assessments for millions of sources. If competitive systems require data at thirty-trillion-token scale from millions of sources, and individuals can maintain at most 150 strong ties, the gap spans 4+ orders of magnitude. That gap will not close through individual effort, and delegation is therefore necessary.

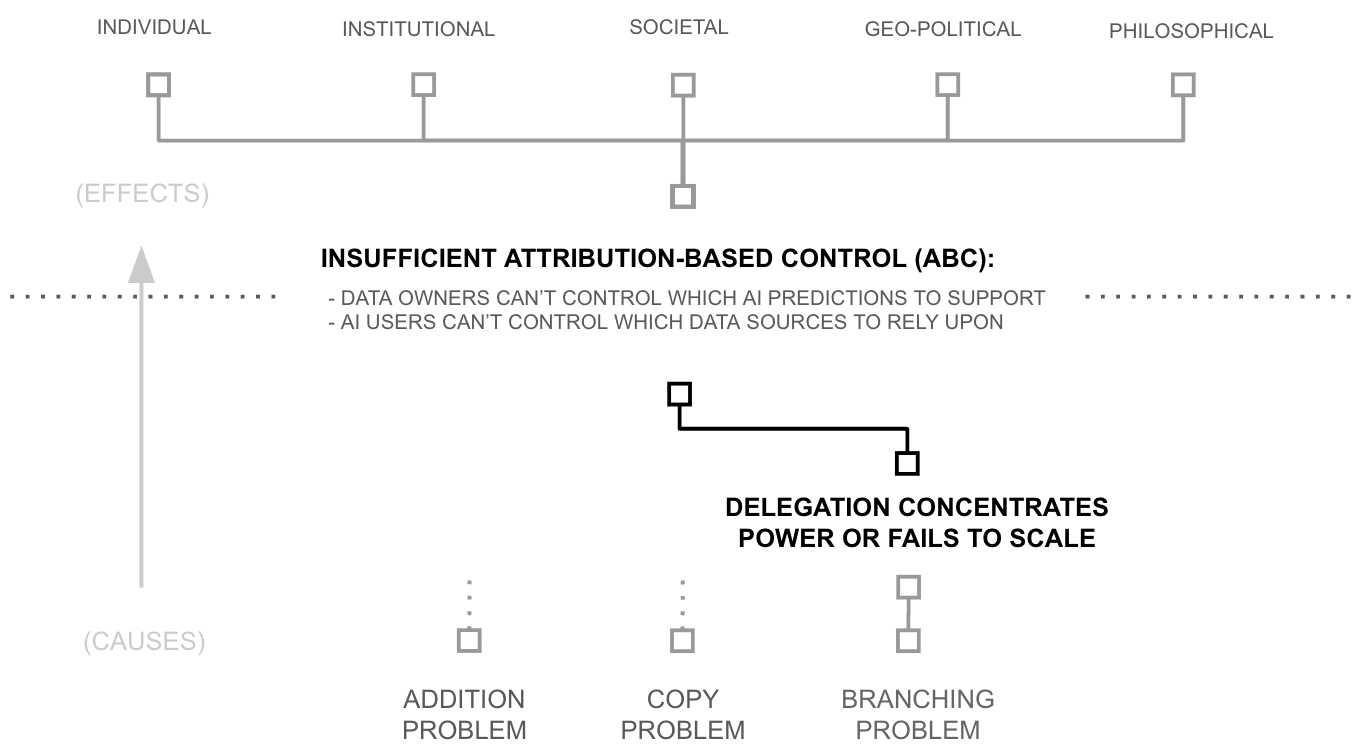

Second Why: Delegation Centralizes or Fails to Scale

Two paths exist: delegate through individuals, or delegate through groups of individuals organized as institutions. One might propose a third path, delegate to technology (to algorithms), but this merely relocates the question; trusting an algorithm means trusting whoever built it and deployed it. The choice reduces to individuals or institutions.

The Institutional Path

The institutional path appears elegant: delegate trust evaluation to AI platforms, let them aggregate signals from billions of sources. But this recreates the architecture NSAI was designed to escape. If users delegate trust evaluation to Google or OpenAI, those institutions decide which sources are trustworthy. Control has not been distributed; it has been relocated. Central institutions cannot deliver ABC by definition.

Consider data owners. As Chapter 2 documented, 6+ orders of magnitude of data remains siloed because data owners do not trust institutional intermediaries with their information. This resistance is rational. Data owners are one of millions; the institution has no particular stake in protecting any single owner's interests. Without mutual stakes, data owners have no mechanism to hold institutions accountable, only the hope that the institution will behave well.

Consider governments. The company Klout processed forty-five billion social interactions daily to score 750 million users, attracted $200 million in acquisition value, and served over two thousand business partners. Western society shut it down anyway... the day GDPR took effect. Privacy regulation made Klout's level of trust evaluation illegal by making its level of surveillance illegal. Yet, GDPR is not a local legislation targeted at specific companies like Klout, it is a European wide paradigm shift in privacy expectations, inspiring similar legislation around the world.

Or consider accountability generally within western society. General trust evaluation at scale requires significant surveillance and likely a significant power imbalance between the surveiller and surveilled. Yet, democratic values prohibit comprehensive surveillance. There is no policy that satisfies both constraints, or a widely deployed technology that circumvents them. Caught between these imperatives, Western societies pay the costs of both while achieving the full benefits of neither.

The result is visible in current online infrastructure. A handful of social media platforms observe approximately 8.5% of all waking human experience on earth... four trillion hours annually. This is surveillance at civilizational scale, yet the online trust verification problem remains woefully unsolved: half of web traffic is bots, up to 30% of online reviews remain fraudulent, and state actors operate troll factories at scale.

The Individual Path

The alternative is delegation through individuals: trust your friends and colleagues to evaluate sources on your behalf. This preserves what institutions cannot offer: strong-ties. Your friend has 150 relationships, not two billion; you are one of 150, not one of millions; and your friend depends on your continued relationship for support, reciprocity, and reputation within your shared community. If your friend misleads you, they lose something they value. The mutual stakes that make trust enforceable remain intact.

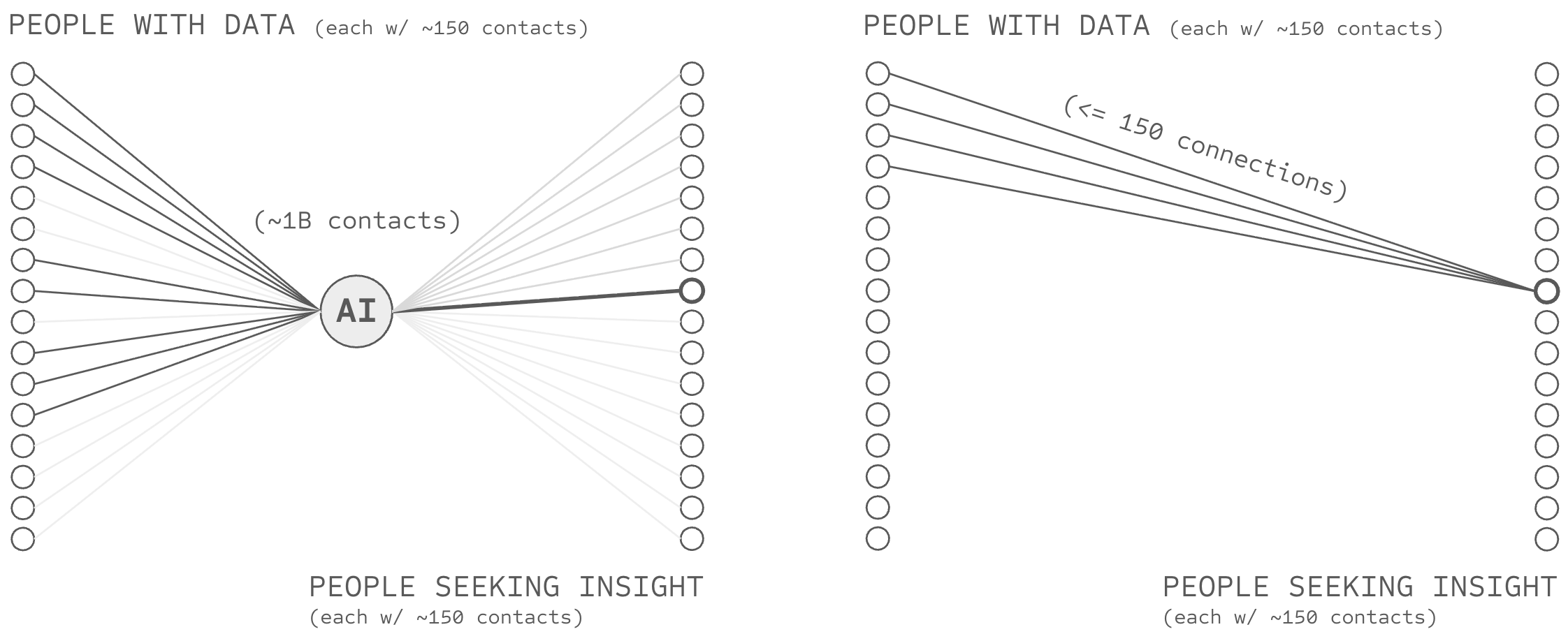

But individual delegation cannot reach the scale that competitive AI platforms require. The Dunbar limit applies to delegated relationships as surely as direct ones. If each friend evaluates within their limit of 150, and you have 150 friends, your network reaches at most 22,500 sources, at best 2+ orders of magnitude short of the millions of sources that competitive AI systems require.

Taken together, institutions fail because they struggle to secure a public mandate for sufficient surveillance, and because they cannot sustain mutual stakes at scale. Individuals preserve mutual stakes but cannot reach AI-level scale. Both paths appear closed.

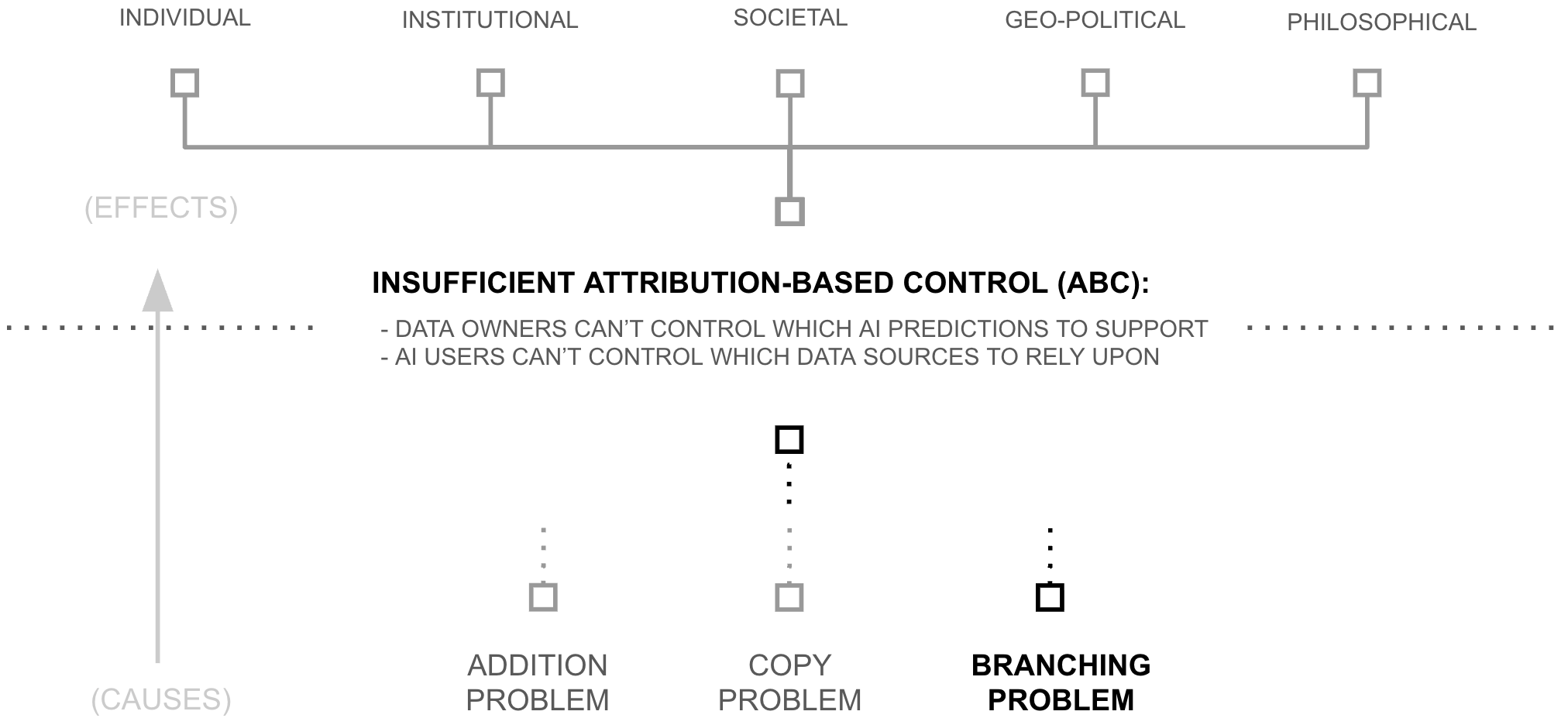

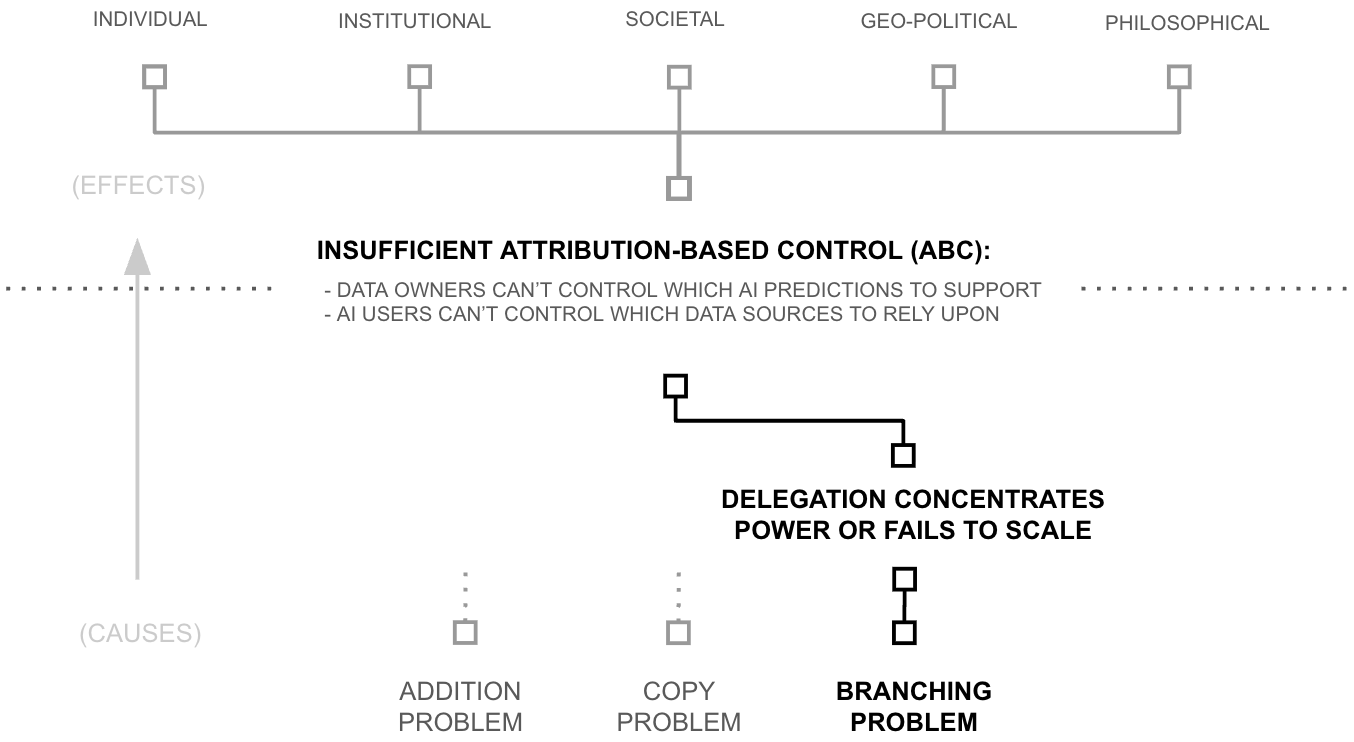

Third Why (Root Cause): The Branching Problem

Consider what happens when nodes of vastly different cardinality connect. One institution sits in the middle, billions of sources connect on one side, billions of users on the other. Now ask: what stake does each party have in the relationship? The institution has two billion connections; if it loses one, it loses one two-billionth of its network. But a user has perhaps 150 relationships, constrained by the same cognitive limits that necessitated delegation in the first place.

The stakes are asymmetric. The institution can betray counterparties at negligible cost; their departure costs it nothing it would notice. Mutual stakes require that both parties in each relationship lose something meaningful if the relationship fails. When one side of an edge has two billion connections and the other side has 150, the asymmetry is structural, and accountability cannot survive it.

The Branching Problem

Trust cannot traverse non-Dunbar-scale nodes. Nodes operating above Dunbar scale (k >> 150) cannot sustain strong-tie relationships with any counterparty. Nodes operating below it (k << 150) underutilise capacity and concentrate dependency. Imbalance between connected nodes creates asymmetric stakes that undermine accountability. Trust breaks wherever nodes deviate from Dunbar-scale operation.

The Branching Puzzle

Competitive AI systems require trust paths to billions of sources, yet the branching problem prohibits any node from connecting to more than ~150 counterparties. Short paths to billions require high-branching nodes; high-branching nodes break trust. The branching puzzle: how can trust delegation reach global scale when trust fails at any node exceeding Dunbar-scale operation?

The Oncologist and the Branching Puzzle

A patient receives a troubling test result and needs an oncologist. Two paths exist.

The platform path. The patient consults a review platform with two billion users and tens of thousands of oncologist reviews. The platform's algorithm surfaces a five-star physician. The patient books an appointment, receives treatment, and dies eighteen months later from a cancer that a competent oncologist would have caught. The review was fake... posted by a marketing firm working for the oncologist and undetected by the platform. The patient is dead, but what does the platform lose? One two-billionth of its user base. The loss is invisible to the platform; the accountability is virtually nonexistent.

The friend path. The patient asks their 150 friends whether anyone knows a good oncologist. No one does—oncology is specialised, and the patient's immediate network lacks relevant experience. The patient asks friends to ask their friends: 150 times 150 yields 22,500 people, still no oncologist referral with direct experience. The information exists somewhere in the social fabric, but three hops away, four hops away, beyond the reach of the patient's strong-tie network. The patient gives up and returns to the platform.

Both paths fail. One has reach without accountability. The other has accountability without reach. The branching puzzle: is there a third path that offers both?

Third Hypothesis: Reach via Recursion

There is a third path: recursion. If each node maintains k connections and trust propagates through chains of depth H, theoretical reach scales as O(kH). Fifty connections across six hops has the theoretical potential to reach fifteen billion sources:

Reach = kH = 506 = 15,625,000,000

This is mathematical possibility, not a claim about actual social networks, but the pattern has precedent. Word of mouth has operated this way for thousands of years; the spread of fire-making, agriculture, and religious ideas all propagated through peer networks without central coordination. Academic citation networks, PageRank, and Wikipedia exhibit similar structure: researchers cite dozens of sources, pages link to dozens of others, editors assess within their capacity, and no central node determines outcomes.

Reframing the Problem

This perspective reframes the problems documented in the three Whys as one of scaling existing word-of-mouth mechanisms. Word of mouth involves several operations: sharing information with contacts, filtering what to pass along, aggregating responses, and weighting sources by trust. Communication infrastructure has upgraded word of mouth's mechanisms unevenly for centuries. The printing press scaled sharing while leaving filtering and aggregation at human speed. Digital infrastructure continued it... sharing now operates instantly, but filtering, aggregating, and trust-weighting still require human attention at each hop.

And when sharing scales but aggregation does not, bottlenecks form at whoever can aggregate, concentrating power into an attention economy. The branching problem and the corresponding collapse of mutual stakes trace to the uneven development of communication infrastructure.

Second Hypothesis: Delegation Without Concentration

The Third Hypothesis established that recursive networks can achieve global reach without high-branching nodes, but mathematical possibility does not guarantee practical implementation. The question is whether recursive trust propagation can avoid centralizing under competitive pressure.

The Propagation Mechanism

Each participant maintains trust assessments $w_{u,v}^d \in [0,1]$ for direct contacts, where $d$ indexes the domain. Trust propagates via iterated computation. Let $T_h(n)$ denote participant $n$'s trust score at hop $h$. Trust originates with the querying user and propagates as each participant distributes to contacts:

$$\text{Map}_n(T_h(n)) = \{(v, T_h(n) \cdot w_{n,v}^d) : v \in \text{contacts}(n)\}$$

Recipients aggregate incoming trust via probabilistic OR:

$$T_{h+1}(m) = 1 - \prod_{i=1}^{k}(1 - T_h(n_i) \cdot w_{n_i,m}^d)$$

After $H$ iterations, trust scores determine how much each source influences the response. The final budget allocation normalizes these scores:

$$B(s) = \frac{T_H(s)}{\sum_{s'} T_H(s')}$$

Why It Scales

The mechanism requires O(k · H) operations per participant per query, where k is the number of contacts and H is the number of hops. With k ≈ 50 and H ≈ 6, each participant performs roughly 300 operations regardless of total network size. The computational cost of reaching billions of sources through recursive propagation does not require any participant to perform billions of operations.

Why It Decentralizes

Each participant controls only their own weights (the assessments they maintain about their own contacts) and no participant controls anyone else's. When trust propagates through a chain, each node applies its own assessments, but those assessments affect only the next hop. No node observes the full chain from query to response, and no node substitutes its judgment for the judgment of other participants in the network.

First Hypothesis: The Machinery Exists

The Second Hypothesis showed that recursive delegation scales and decentralizes in principle. Whether anyone uses it depends on two requirements: participation must be cheap enough to compete with platforms, and secure enough that honest participation is rational.

What Deep Voting Provides

Recursive consultation through social networks presently requires human effort at every hop: formulating requests, providing context, waiting for responses, following up when people forget. A chain that could theoretically reach a relevant expert in four hops might take days or weeks in practice. Meanwhile, platform queries from frontier AI systems can return results in seconds.

Deep voting addresses this gap by describing how this analog process could be done digitally, plausibly giving a path towards a significant reduction in cost and latency. It did this in part by separating weight specification from query-time coordination. Participants record trust assessments in advance, specifying which contacts they trust for which domains. When a query arrives, the system propagates trust according to these pre-recorded weights without requiring human attention.

What Structured Transparency Provides

Recording trust assessments in a digital system creates vulnerability that face-to-face word of mouth does not. If assessments are observable, employers could identify employees who distrust company sources, governments could identify citizens who trust opposition voices, and commercial actors could infer relationships for targeted manipulation. Rational participants facing these risks would either decline to participate or provide strategically dishonest assessments.

Structured transparency addresses this by enabling something analogous to end-to-end encryption for the trust propagation process. Information flows from participants to intended recipients without requiring any central intermediary to observe unencrypted weights or messages.

The Gap Closes

The First Why identified a gap between cognitive capacity for trust evaluation—approximately 150 relationships—and the number of sources requiring evaluation—approximately 109. Seven orders of magnitude.

Recursive depth addresses the gap structurally. Deep voting replaces human coordination with computation, making recursive consultation plausibly fast enough to compete with platforms. Structured transparency protects assessments from observation, making honest participation possible without exposure.

The contribution is not the pattern of recursive trust propagation, which has operated in human societies for as long as those societies have existed. The contribution is identifying the infrastructure barriers—coordination cost and privacy risk—and providing machinery that addresses them.

Conclusion

This chapter asked whether the problems documented in the three Whys admit a solution. The Third Hypothesis established that recursive networks can achieve global reach without requiring any node to exceed Dunbar-scale operation. The Second Hypothesis showed that a specific propagation mechanism scales computationally and distributes authority structurally. The First Hypothesis showed that deep voting addresses coordination cost and structured transparency addresses privacy risk.

What the chapter establishes is architectural possibility, not guaranteed outcome. Whether the machinery proves sufficient to motivate adoption, and whether the architectural properties prove robust against competitive dynamics, remain empirical questions.

The chapter also proposed a reframe. The three Whys traced concentration not to any fundamental constraint on distributed trust, but to uneven development of communication infrastructure—sharing scaled while filtering, aggregating, and trust-weighting remained at human speed. The contribution of this thesis is not the pattern of recursive trust propagation, which is ancient. The contribution is identifying the infrastructure gaps that prevented the pattern from operating at scale, and surveying and re-framing recently proposed machinery that addresses them.

References

- (1993). Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16(4), 681–735.

- (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380.

- (1985). Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510.

- (2007). Complex Contagions and the Weakness of Long Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 113(3), 702–734.

- (1988). Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120.

- (2012). Four Degrees of Separation. ACM Web Science 2012, 33–42.

- (1997). The Attention Economy and the Net. First Monday, 2(4).

- (2024). Digital 2024: Global Overview Report. Hootsuite & We Are Social.

- (2024). 2024 Bad Bot Report. Imperva Research Labs.

- (2022). The GDPR and Its Influence on Global Data Privacy Legislation. Journal of Data Protection & Privacy.

- (2015). Klout and Social Scoring. Wired.

- (1981). The Evolution of Cooperation. Science, 211(4489), 1390–1396.