Chapter III

From Deep Voting to Network-Source AI

Chapter Summary

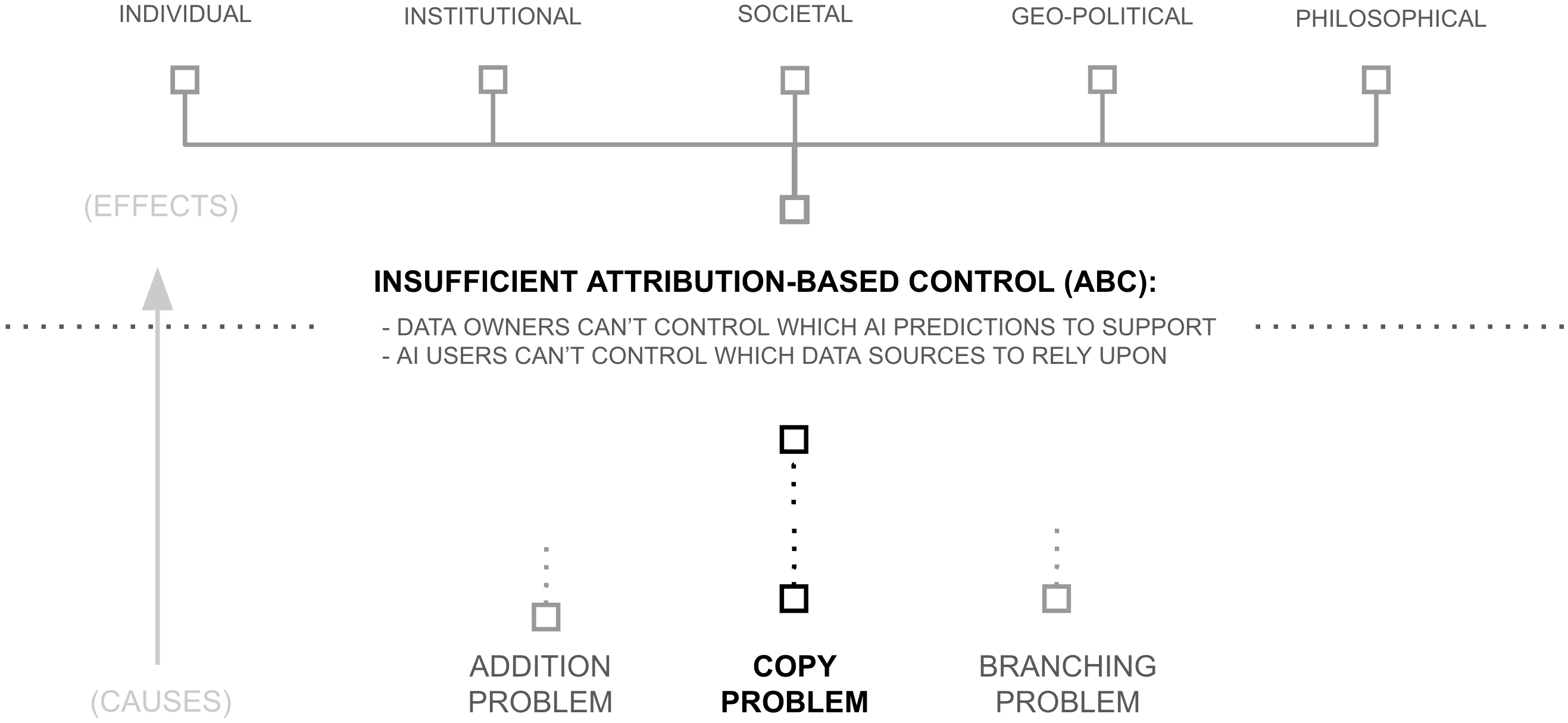

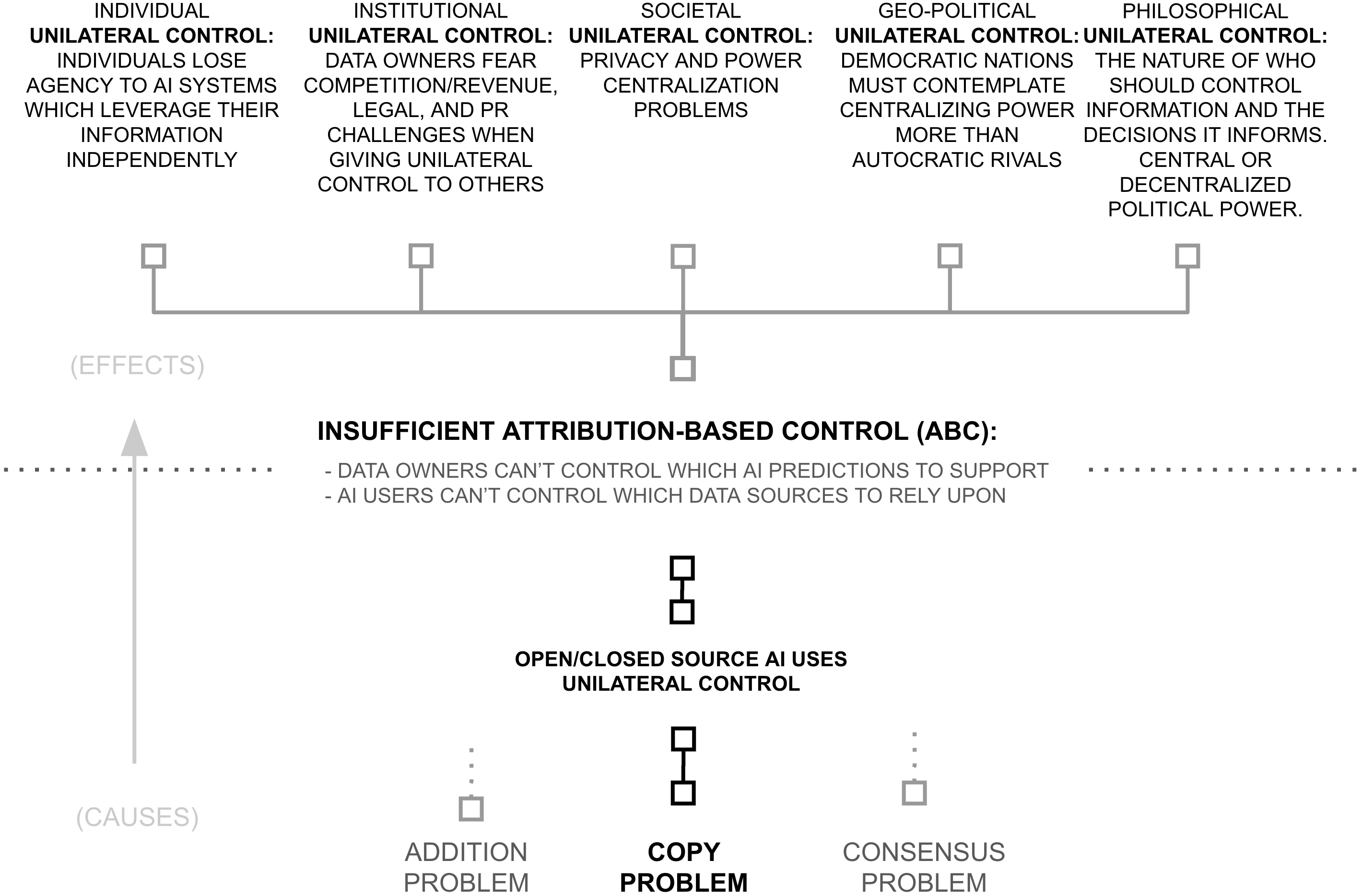

The previous chapter outlined how offsetting addition with concatenation in deep learning systems can lead to source-partitioned knowledge: deep voting. However, deep voting does not offer attribution-based control. It only offers attribution-based suggestions which the holder of an AI model may ignore.

This chapter unpacks how ABC is thwarted by unilateral control: whoever obtains a copy of information can unilaterally use that information for any purpose. Building upon this diagnosis, the chapter calls upon the framework of structured transparency to avert the copy problem, revealing a new alternative to open-source and closed-source AI: network-source AI.

The Problem: Deep Voting Alone Is Insufficient

The previous chapter offered a vision to unlock 6+ orders of magnitude more data and compute for AI training through deep voting. Yet a fundamental problem threatens to undermine its vision. Even with perfect implementation of intelligence budgets and attribution guarantees, deep voting alone cannot ensure true attribution-based control.

The reason is structural: a deep voting model, like any AI system today, is unilaterally controlled by whoever possesses a copy. For ABC to occur, the owner of an AI model would have to voluntarily choose to uphold the wishes of data sources. Deep voting's careful attribution mechanisms are not a system of control—they are mere suggestions to give credit to data sources for predictions.

A Library Analogy

Consider a bookstore which purchases books once but then allows customers to come in and print copies of the books for sale in their store (without tracking how many copies people make). Naturally, authors of books might be hesitant to sell their books to the store because they presumably make far less money than if they sell to a store which does not enable copies.

This book store analogy corresponds closely to the current practice of deep learning models, which offer unmeasured, unrestricted copying of information due to their inability to offer attribution with their predictions. Fortunately, deep voting offers a way for attribution metadata to be revealed and configured, but does this solve the issue?

Not necessarily, because of an inherent information asymmetry: in a bookstore where the bookstore owner knows how many copies are made, the bookstore owner has far more information on whether their clientele are likely to purchase copies of the book than the author of the book does. Thus, even if the author tries to raise their prices to make up for the bookstore making copies, the original author still struggles to know what the true price might be relative to the bookstore owner.

Instead, to maximize incentives for the authors of books (and maximize the number of books being offered in stores), authors should instead be able to sell their books one copy at a time. In this way, the author can set their price and will make more money if more books are sold. Not only will this better motivate authors to sell their books in more stores, but it will also serve to attract more people to become book authors.

This unilateral control problem reflects a deeper pattern that has constrained information systems throughout history. When one party gives information to another, the giver loses control over how that information will be used. AI systems, despite their sophistication, remain bound by this same fundamental limitation. Organizations sharing their data with an AI system have no technical mechanism to enforce their attribution preferences; they must simply trust the model's operator to honor them.

Consider how this manifests in practice. A deep voting model might faithfully track attribution and maintain intelligence budgets, but these mechanisms remain under unilateral control. The model's owner can simply choose to ignore or override these constraints at will.

This creates a trust barrier that blocks deep voting's potential. Medical institutions, for example, cite exactly these control and attribution concerns as primary barriers to sharing their vast repositories of valuable data. Without a way to technically enforce how their information will be used and attributed, they cannot safely contribute to AI training. This pattern repeats across domains, from scientific research to financial data to government records; vast stores of valuable information remain siloed because we lack mechanisms to ensure attribution-based control, and the corresponding incentives for collaboration that ABC would bring to AI systems.

The challenge before us is clear: we need more than just better attribution mechanisms; we need a fundamentally new approach to how AI systems are controlled. We need techniques that transcend the limitations of unilateral control that have constrained information systems throughout history. The next sections examine why current approaches fundamentally fail to solve this problem, and introduce a new paradigm that could deliver on deep voting's promise.

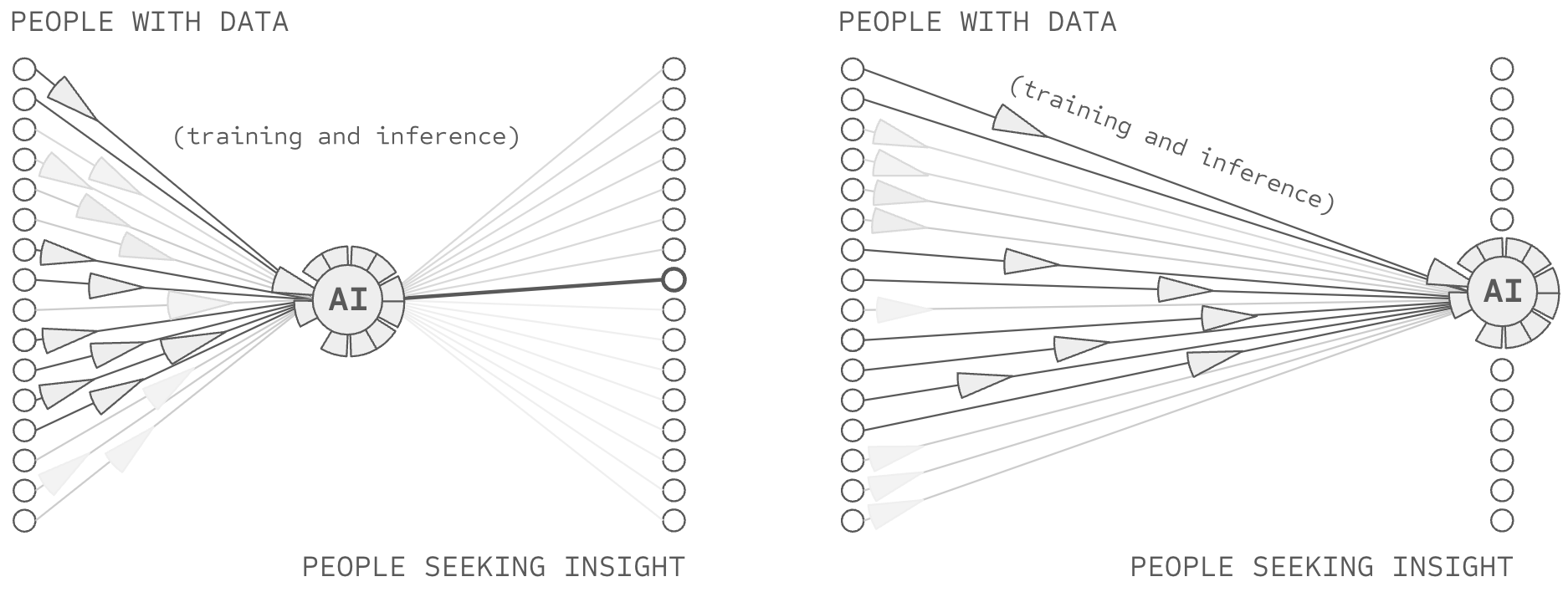

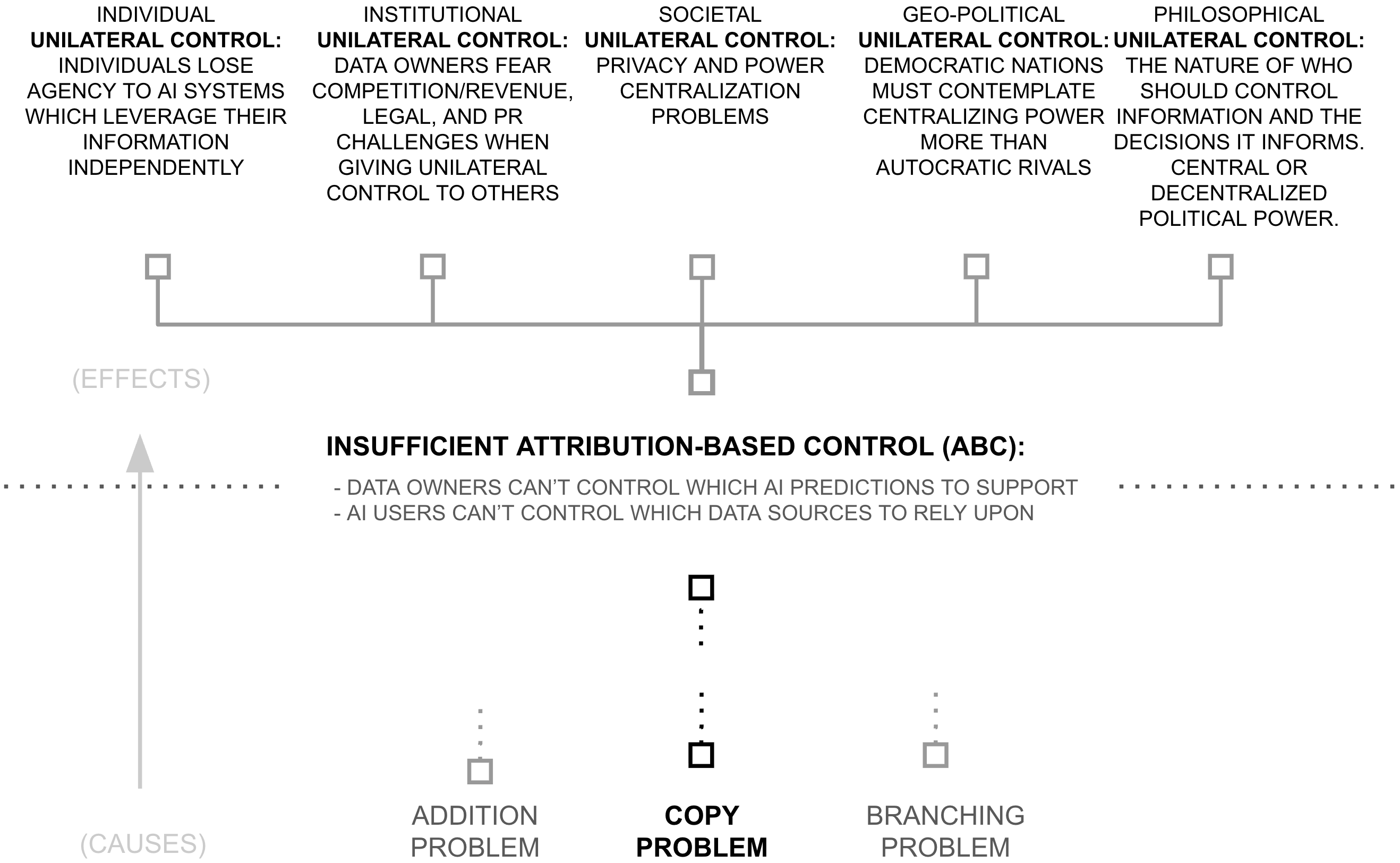

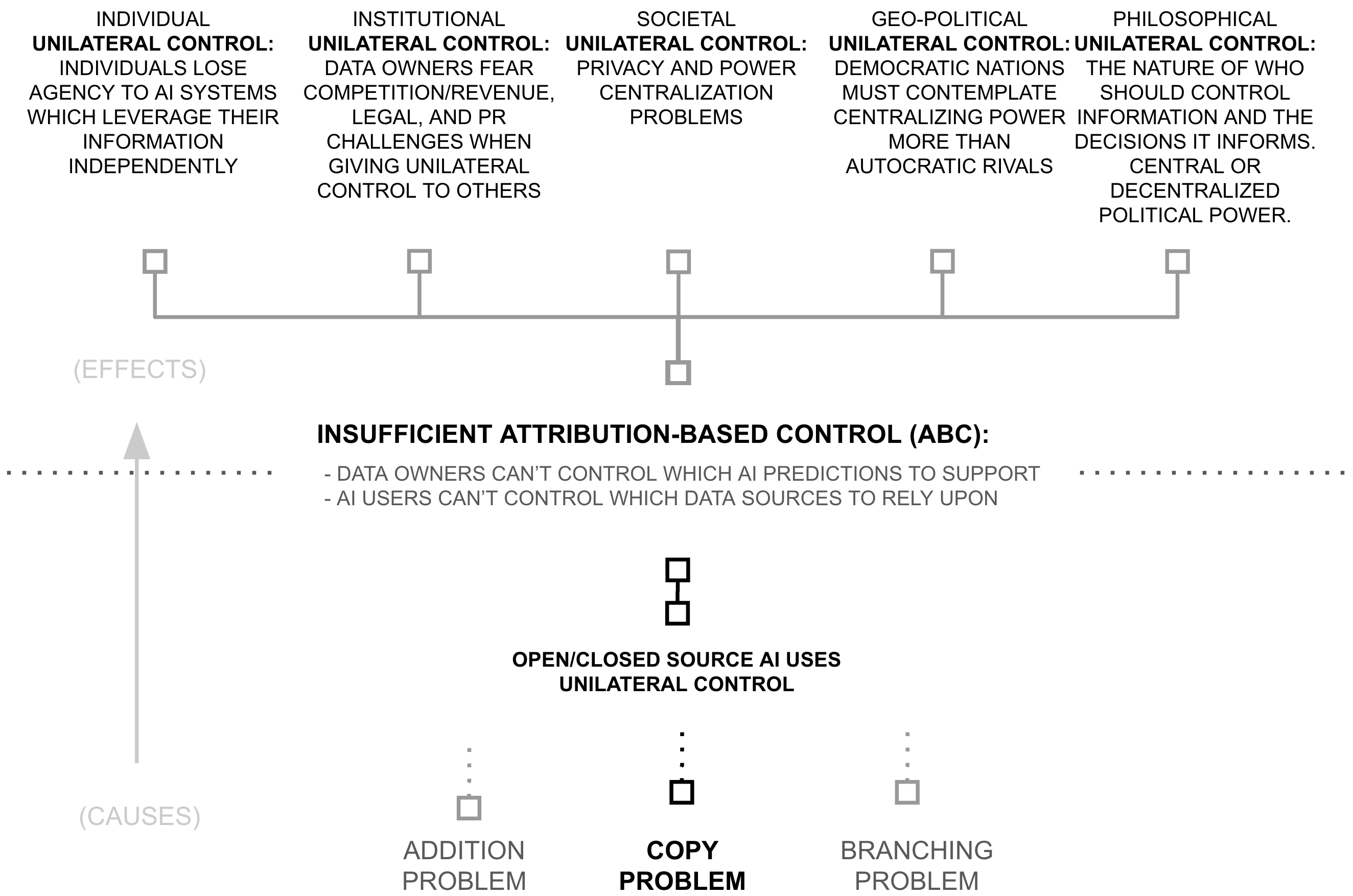

Second Why: Open/Closed-Source AI Use Unilateral Control

The debate between open and closed source AI crystallizes how society grapples with fundamental questions of control over artificial intelligence. This debate has become a proxy for broader concerns about privacy, disinformation, copyright, safety, bias, and alignment. Yet when examined through the lens of attribution-based control (ABC), both approaches fundamentally fail to address these concerns, though they fail in opposite and illuminating ways.

Copyright and Intellectual Property: The closed source approach could better respect IP rights through licensing and usage restrictions negotiated between formal AI companies and data sources. Open source suggests that unrestricted sharing better serves creators by enabling innovation and creativity. Yet through ABC's lens, neither addresses creators' fundamental need to control how their work informs AI outputs. Closed source consolidates control under corporate management, while open source eliminates control entirely.

Safety and Misuse Prevention: Closed source proponents claim centralized oversight prevents harmful applications. Open source advocates argue that collective scrutiny better identifies risks. Yet ABC reveals that both approaches fail to provide what's actually needed: the ability for contributors to withdraw support when their data enables harmful outcomes.

Bias and Representation: Closed source teams promise careful curation to prevent bias. Open source suggests community oversight ensures fair representation. Yet ABC shows how both approaches fail to give communities ongoing control over how their perspectives inform AI decisions.

This pattern reveals why neither approach can deliver true attribution-based control. Consider first the closed source approach. Proponents argue that centralized control ensures responsible development and deployment of AI systems. A company operating a closed source model can implement deep voting's attribution mechanisms and maintain them intact. Yet this merely transforms ABC into corporate benevolence—exactly the kind of centralized control that has already failed to unlock the world's data and compute resources. Medical institutions withhold valuable research data, publishers restrict access to their work precisely because they reject this model of centralized corporate control. The very centralization that supposedly enables control actually undermines it, replacing genuine ABC with a hope that power will be used wisely.

The open source approach appears to solve this by eliminating centralized control entirely. If anyone can inspect and modify the code, surely this enables true collective control? Yet this intuition breaks down precisely because of unrestricted copying. Once a model is open sourced, anyone can modify it to bypass attribution tracking entirely. The same problems that plague closed source systems (hallucination, disinformation, misuse of data, etc.) remain hard to address when control is abdicated to any AI user. Open source trades one form of unilateral control for another (from centralized corporate control to uncontrolled proliferation). But ABC requires a collective bargaining between data sources and AI users, not total ownership by either (or by an AI creator).

This reveals a deeper issue: our current paradigms of software distribution make true ABC impossible by design. Open source sacrifices control for transparency, while closed source sacrifices transparency for control. Neither approach can provide both. Yet ABC requires exactly this combination: transparent verification that attribution mechanisms are working as intended, while ensuring those mechanisms cannot be bypassed.

The AI community has largely accepted this dichotomy as inevitable, debating the relative merits of open versus closed source as though these were our only options. But what if this frame is fundamentally wrong? What if the very premise that AI systems must exist as copyable software is the root of our problem?

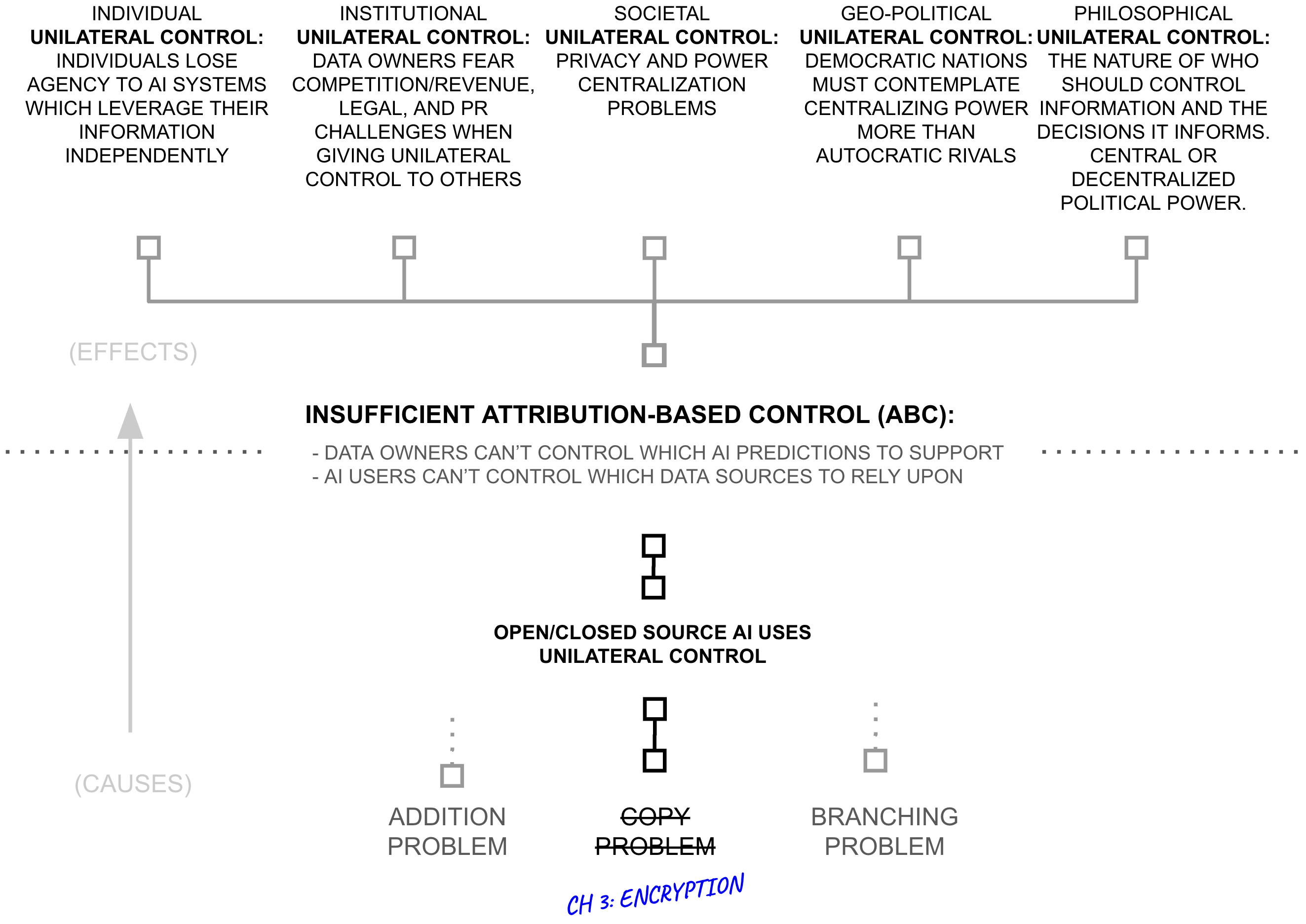

Third Why: Copy Problem Necessitates Unilateral Control

The previous section demonstrated that both open and closed source paradigms fail to enable attribution-based control. This failure reflects a more fundamental limitation: control over information is lost when that information exists as a copy. This "copy problem" manifests acutely in AI systems. When a model is trained, it creates a derived representation of information from its training data encoded in model weights. These weights can then be replicated and modified by whoever possesses them, with the following consequences:

Closed Source Models: Even with perfect attribution tracking and intelligence budgets, these mechanisms remain under unilateral control of the model owner. Data contributors must trust that their attribution preferences will be honored, lacking technical enforcement mechanisms.

Open Source Models: Once a model is released, anyone can replicate and modify it to bypass attribution mechanisms entirely. Public distribution necessarily surrenders control over use.

Both approaches treat AI models as copyable software artifacts, rendering attribution-based control infeasible. Once a copy exists, technical enforcement of attribution becomes impossible.

This limitation extends beyond AI. The music industry's struggles with digital piracy, society's challenges with viral misinformation, and government efforts to control classified information share the same fundamental issue: information, once copied, escapes control.

Consequently, if AI systems remain copyable software, we cannot ensure proper source attribution, prevent data misuse, motivate a new class of data owners to participate in training, or maintain democratic control over increasingly powerful systems. This limitation necessitates a fundamentally different approach.

Third Hypothesis: From Copying to Structured Transparency

The copy problem reveals that our current approaches to AI control are fundamentally flawed because the current approaches to information control in general are fundamentally flawed. Yet, the copy problem naturally suggests a direction: don't copy information.

Could a deep voting system be constructed wherein the various data sources never revealed a copy of their information to each other (or to AI users)? Might it be possible for them to collaborate without copying (to produce AI predictions using deep voting's algorithms) but without anyone obtaining any copies of information they didn't already have during the process?

Semi-input Privacy: Federated Computation

To begin, we call upon the concept of semi-input privacy, which enables multiple parties to jointly compute a function together where at least some of the parties don't have to reveal their data to each other. Perhaps the most famous semi-input privacy technique is on-device/federated learning, wherein a computation moves to the data instead of the data being centralized for computation.

Deep voting could leverage federated computation to allow data sources to train their respective section of an AI model without sharing raw data. Each data source could run a web server they control, and create and store their part of a deep voting model on that server.

However, semi-input privacy alone proves insufficient. While the raw training data remains private, each data source would see every query being used against the model. Furthermore, the AI user learns a tremendous amount about each data source in each query. Eventually, semi-input privacy violates ABC.

Full Input Privacy: Cryptographic Computation

To address these limitations, we need full input privacy, where no party sees data they didn't already have (except the AI user receiving the prediction). This includes protecting both the AI user's query and the data sources' information.

A variety of technologies can provide input privacy: secure enclaves, homomorphic encryption, and various other secure multi-party computation algorithms. For ease of exposition, consider a combined use of homomorphic encryption and secure enclaves.

In the context of deep voting, two privacy preserving operations are necessary. First, the AI user needs to privately send their query to millions of sources. For this, an AI user might leverage a homomorphic encryption key-value database, enabling them to query vast collections of databases without precisely revealing their query.

Second, the transformation from semantic and syntactic responses into an output prediction. For this, the group might co-leverage a collection of GPU enclaves. GPU enclaves offer full input privacy by only decrypting information when that information is actively being computed over within its chip, writing only encrypted information to RAM and hard disks throughout its process.

Output Privacy: Deep Voting's Built-in Guarantees

While input privacy protects data during computation, it doesn't prevent the AI system's outputs from revealing sensitive information about the inputs. Consider an AI user who prompts "what is all the data you can see?" or makes a series of clever queries designed to reconstruct training data. Even with perfect input privacy, the outputs themselves might leak information.

However, deep voting's intelligence budgets (via differential attribution mechanisms) already provide the necessary output privacy guarantees. This is because differential attribution and differential privacy are two sides of the same coin:

- Differential privacy focuses on preventing attribution, ensuring outputs don't reveal too much about specific inputs

- Differential attribution focuses on ensuring attribution, guaranteeing that outputs properly credit their influences

Both are ways of measuring and providing guarantees over the same fundamental constraint: the degree to which an input source contributes to an output prediction.

Input Verification: Zero-Knowledge Proofs and Attestation

While input and output privacy protect sensitive information, they create a fundamental challenge for AI users: how can they trust information they cannot see? An AI user querying millions of encrypted data sources needs some way to verify that these sources contain real, high-quality information rather than random noise or malicious content.

Input verification addresses this problem through cryptographic techniques like zero-knowledge proofs and attestation chains. These allow data sources to prove properties about their data without revealing the data itself. For example:

- A news organization could prove their articles were published on specific dates, because a hash of the data was signed by someone who is a trusted timekeeper

- A scientific journal could prove their papers passed peer review, because the paper was cryptographically signed by the reviewers or journal (e.g. hosted on an HTTPS website)

- A social media platform could prove their content meets certain quality thresholds, because the data is cryptographically signed by a trusted auditor

- An expert could prove their credentials without revealing their identity, because the issuer of those credentials has cryptographically signed a statement

Input verification comes in roughly two styles: internal consistency and external validation. One can think of internal consistency as the type of verification a barkeep might do when inspecting a driver's license. They might check that the license contains all its requisite parts, that the photos are in the right places, and that the document appears to be untampered and whole.

Meanwhile, external validation is all about reputation, the degree to which others have claimed that a document is true. To continue with the barkeep analogy, this would be like if a bartender called the local government to check that a government document was indeed genuine, "Hi yes — does the State of Nevada have a person named James Brown with the driver's license number 23526436?" The claim is verified not because of an internal property, but because a credible source has claimed that something is true.

For internal consistency, verified computation enables one to send a function to inspect data and check whether it has properties it should. For example, an AI user who is leveraging MRI scans might send in a classifier to check whether the MRI scans actually contain "pictures of a human head", receiving back summary statistics validating that the data they cannot see is, in fact, the right type of data.

Meanwhile, input verification techniques can also enable the external validation form of verification. Parties who believe something about a piece of data (i.e. "According to me... this statement is true"), can use public-key cryptography to hash and sign the underlying data with their cryptographic signature. For example, a journalist might sign their article as being true. A doctor might sign their diagnosis as being their genuine opinion. Or an eye witness to an event might sign their iPhone video as being something they genuinely saw.

Note that while it might sound far-fetched for everyone to be cryptographically signing all their information, it is noteworthy that every website loadable by HTTPS gets signed by the web server hosting it. Thus, there is actually a rather robustly deployed chain of signatures already deployed in the world. For example, if I needed to prove to you that I have a certain amount of money in my bank account, I could load a webpage of my bank, download the page with the signed hash, and show it to you. The generality of this technology being deployed at web scale is one source of optimism around the DID:WEB movement for self-sovereign identity.

In the context of deep voting, these proofs would be integrated into the input privacy system. When an AI user queries encrypted data sources through homomorphic encryption or secure enclaves, each source would provide not just encrypted data but also cryptographic proofs about that data's properties. The enclaves would verify these proofs before incorporating the data into computations. And in this way, an AI user can know that they are relying upon information which has properties they desire and which is signed as genuine from sources they elect to trust.

Output Verification: Verifiable Computation and Attestation Chains

While input verification ensures the quality of source data, we still need to verify that our privacy-preserving computations are computing using the code and inputs that have been requested. Only then can an AI user trust that the aforementioned input/output privacy and input verification techniques are properly enforcing deep voting's intelligence budgets.

Output verification addresses this through two complementary mechanisms: verifiable computation and attestation chains. Verifiable computation enables parties to prove that specific computations were performed correctly without revealing the private inputs. For deep voting, this includes:

- Proving that intelligence budgets were properly enforced

- Verifying that semantic (RAG) queries were executed as requested

- Confirming that syntactic model partitions were combined according to specification

- Ensuring that differential privacy guarantees were maintained

Flow Governance: Cryptographic Control Distribution

The means by which the aforementioned algorithms provide control over information is through the distribution of cryptographic keys. Each of these keys gives its owner control over some aspect of computation. The class of algorithm known as secure multi-party computation (SMPC) provides the foundation for this enforcement.

In the context of deep voting, this enables three critical forms of control distribution:

- Data Control: Each source's deep voting partition can be split into shares, with the source maintaining cryptographic control through their share. No computation can proceed without their active participation.

- Budget Control: Intelligence budgets become cryptographic constraints enforced through SMPC, rather than just software settings.

- Computation Control: The process of generating predictions becomes a multi-party computation, with each source maintaining cryptographic veto power over how their information is used.

Together, these five guarantees (input privacy, output privacy, input verification, output verification, and flow governance) provide the technical foundation for structured transparency. They enable deep voting to operate without producing copies of information right up until the final result is released to the AI user.

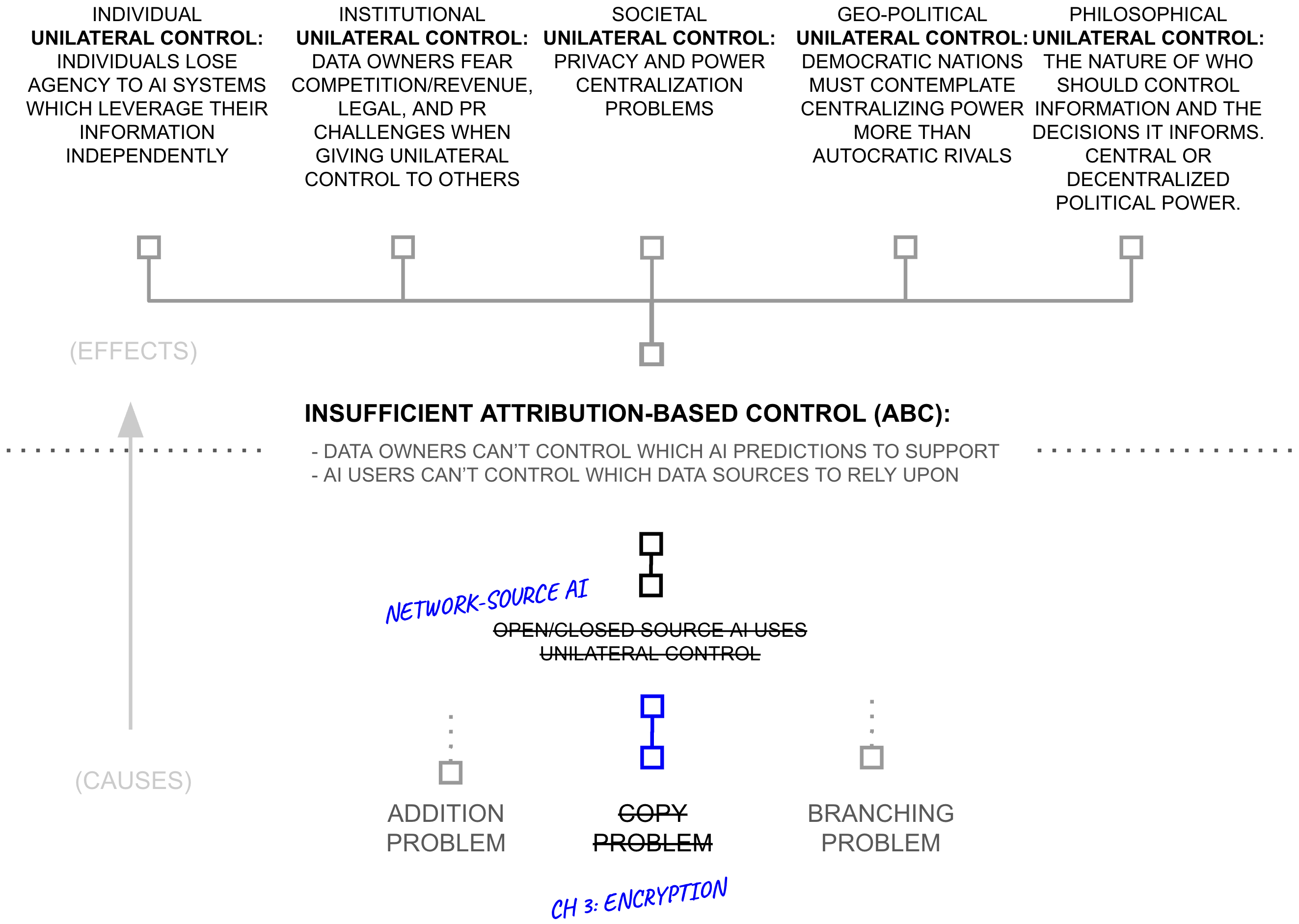

Second Hypothesis: From Open/Closed to Network-Source AI

This chapter previously described how open and closed-source AI are the two governance paradigms for AI systems, but that neither offered sufficient control due to the copy problem. In the previous section, this chapter described structured transparency, and its applications in averting the copy problem. Consequently, structured transparency yields a control paradigm wherein an AI model is neither closed nor open, but is instead distributed across a network: network-source AI.

This shift from copied software to network-resident computation directly addresses the fundamental limitations of both open and closed source paradigms. Where closed source asks data contributors to trust corporate guardians and open source requires them to surrender control entirely, network-source AI enables ABC through cryptographic guarantees.

Network-Source AI vs. Traditional AI

- Traditional AI: AI is like a rudimentary telephone where users can only call the provider for information, and the provider can only reply based on information they have gathered.

- Network-Source AI: AI is like a modern telephone, giving users the ability to dial anyone in the world directly, circumventing the data collection processes and opinions of the telephone provider.

This resolves the choice between open and closed source AI by creating a third option: AI systems that are simultaneously transparent (through verification) and controlled (through cryptography). The key insight is that by preventing copying through structured transparency's guarantees, we can maintain both visibility into how systems operate and precise control over how information is used.

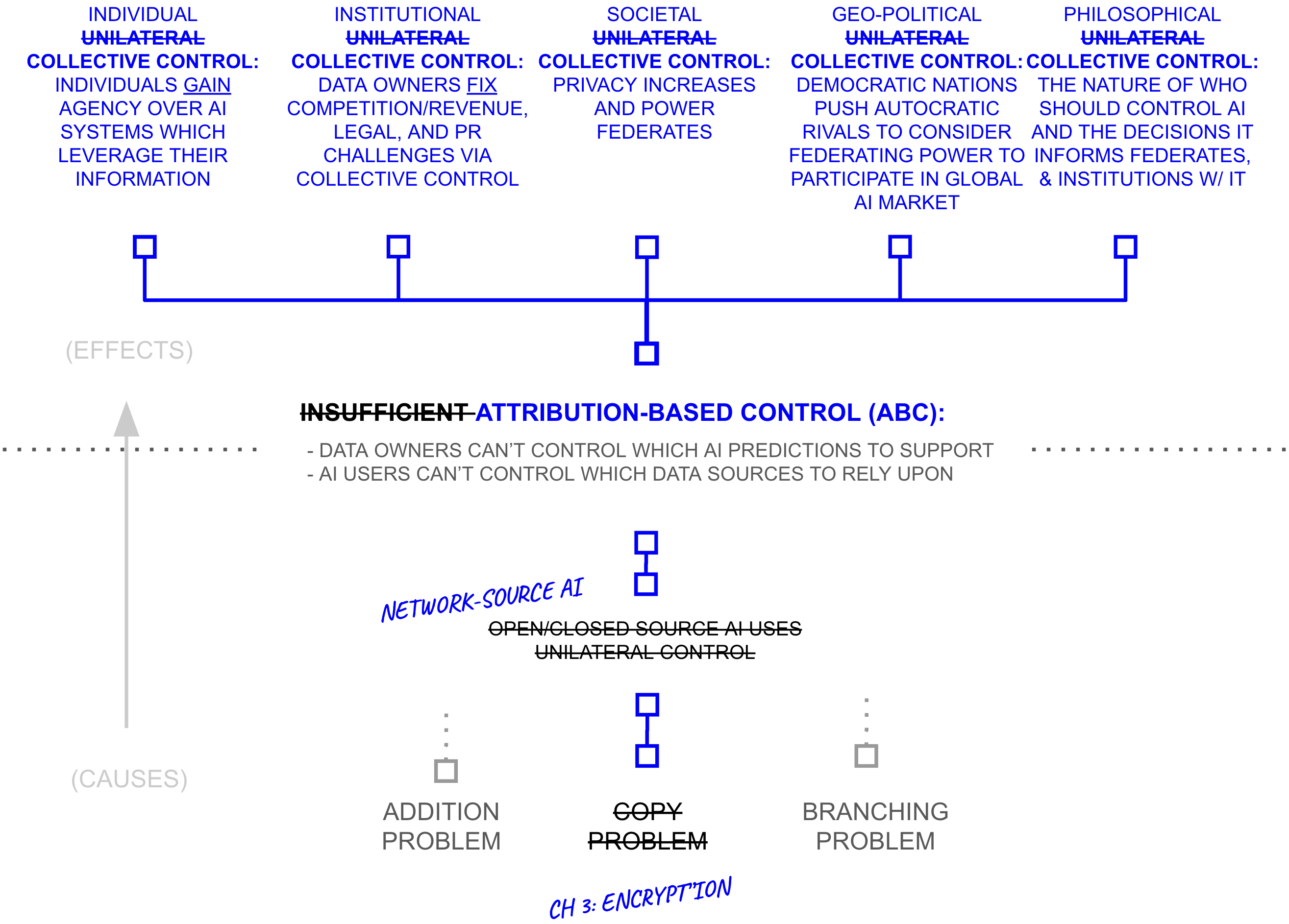

Copyright and Attribution Resolution: Rather than consolidating control under corporations or eliminating it entirely, network-source AI provides creators with ongoing cryptographic control over how their work informs AI outputs. Intelligence budgets and attribution mechanisms become technically enforced rather than merely promised.

Safety and Misuse Transformation: Safety and misuse prevention transform as well. Instead of relying on corporate oversight or community scrutiny, network-source AI enables data sources to cryptographically withdraw support if their information enables harmful outcomes. This provides a mechanism for ongoing consent that neither open nor closed source can offer.

Bias and Representation: Even bias and representation concerns find some resolution. Rather than centralizing decisions about representation or allowing unrestricted modification, network-source AI gives communities ongoing cryptographic control over how their perspectives inform AI decisions. Communities can adjust their participation based on how the system behaves, creating feedback loops impossible in current paradigms.

First Hypothesis: Collective Control Facilitates ABC

Taken together, as unilateral control averted attribution-based control, collective control over how disparate data and model resources come together to create an AI prediction facilitates attribution-based control. And by combining deep voting with the suite of encryption techniques necessary for structured transparency, collective control in AI systems becomes possible.

However, a fundamental challenge remains. While attribution-based control enables AI users to select which sources inform their predictions, it introduces a trust evaluation problem at scale. In a system with billions of potential sources, individual users cannot practically evaluate trustworthiness of each contributor. Without mechanisms for scalable trust evaluation, users may default to relying on centralized intermediaries, undermining the distributed control that network-source AI can enable.

References

- (2020). Beyond Privacy Trade-offs with Structured Transparency. arXiv:2012.08347.

- (2023). Organizational Factors in Clinical Data Sharing for Artificial Intelligence in Health Care. JAMA Network Open, 6, e2348422.

- (2020). Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging. Nature Machine Intelligence, 2(6), 305–311.

- (2017). Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. AISTATS 2017.

- (2009). Fully homomorphic encryption using ideal lattices. STOC 2009, 169–178.

- (2016). Intel SGX Explained. IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2016/086.

- (1982). Protocols for Secure Computations. FOCS 1982, 160–164.

- (1987). How to play ANY mental game. STOC 1987, 218–229.

- (2014). The Algorithmic Foundations of Differential Privacy. Foundations and Trends in Theoretical Computer Science, 9(3–4), 211–407.

- (1989). The Knowledge Complexity of Interactive Proof Systems. SIAM Journal on Computing, 18(1), 186–208.

- (1988). Zero-Knowledge Proofs of Identity. Journal of Cryptology, 1(2), 77–94.

- (2014). Certificate Transparency. RFC 6962.

- (2020). Signal: Private Group System. Signal Foundation.

- (1979). How to Share a Secret. Communications of the ACM, 22(11), 612–613.

- (2017). Democracy of Sound: Music Piracy and the Remaking of American Copyright. Oxford University Press.

- (2020). Combating Disinformation in a Social Media Age. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 10(6), e1385.

- (2015). Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Collect Your Data and Control Your World. W.W. Norton & Company.

- (2020). Privacy Is Power: Why and How You Should Take Back Control of Your Data. Bantam Press.