Chapter II

From Deep Learning to Deep Voting

Chapter Summary

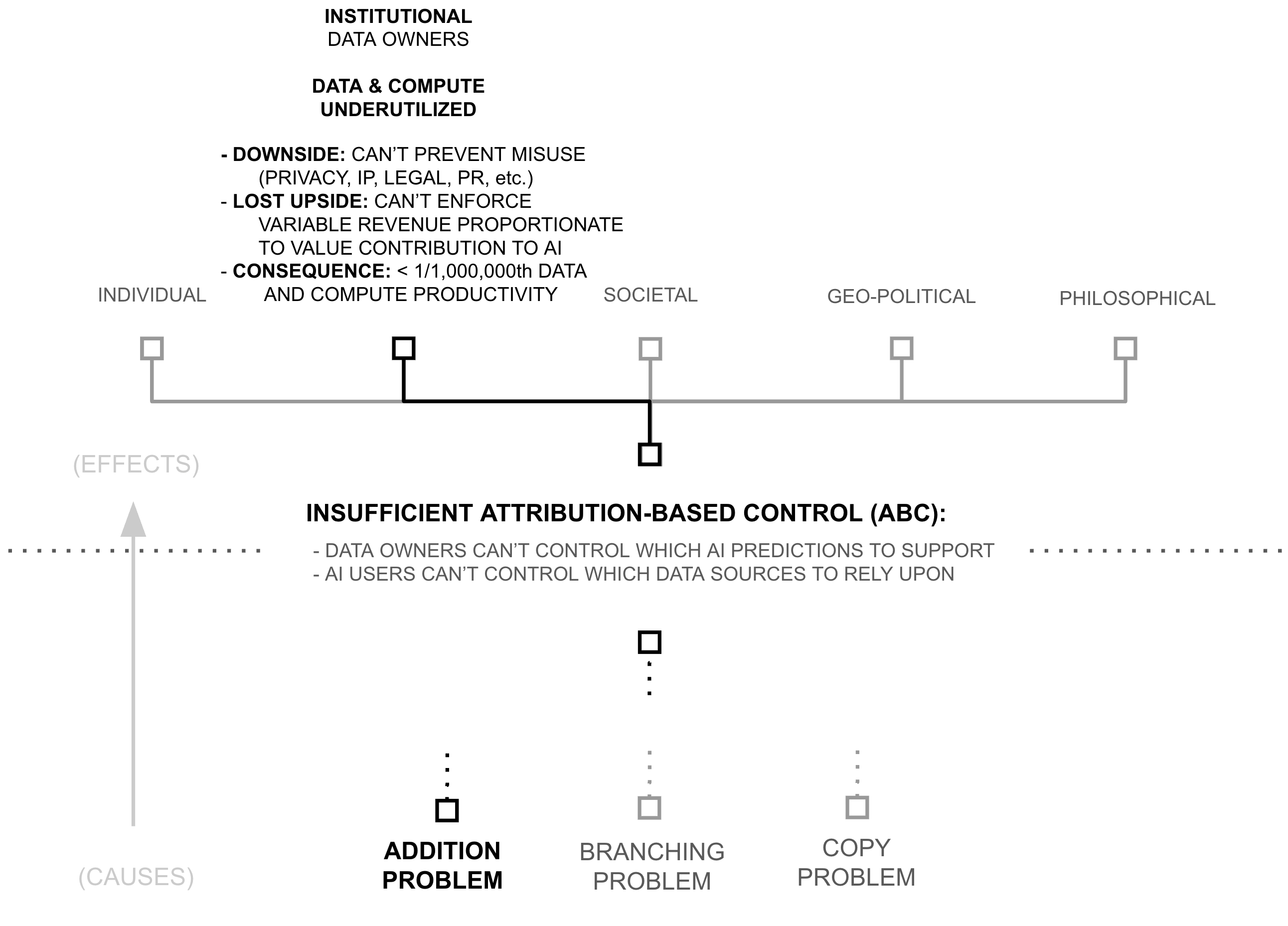

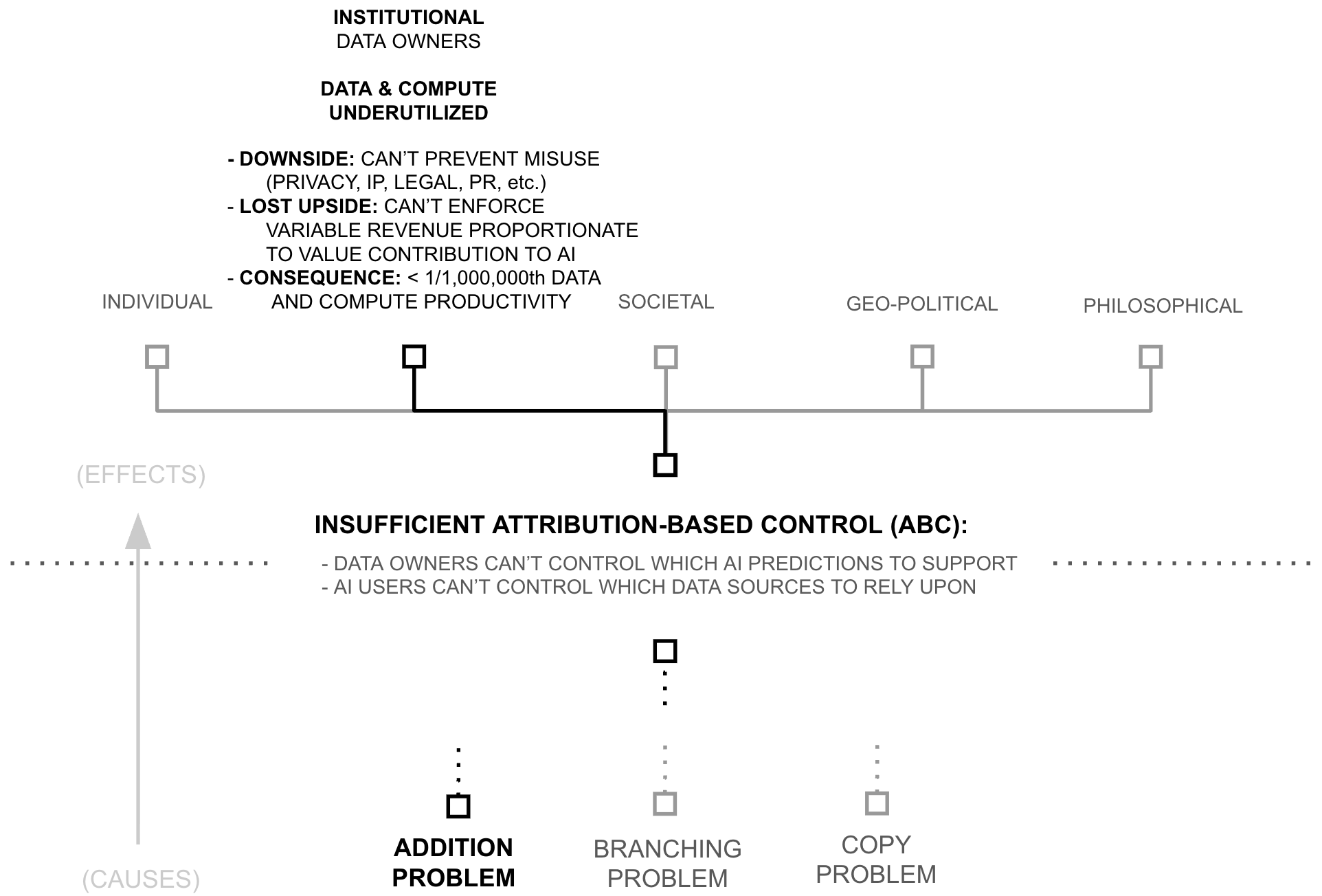

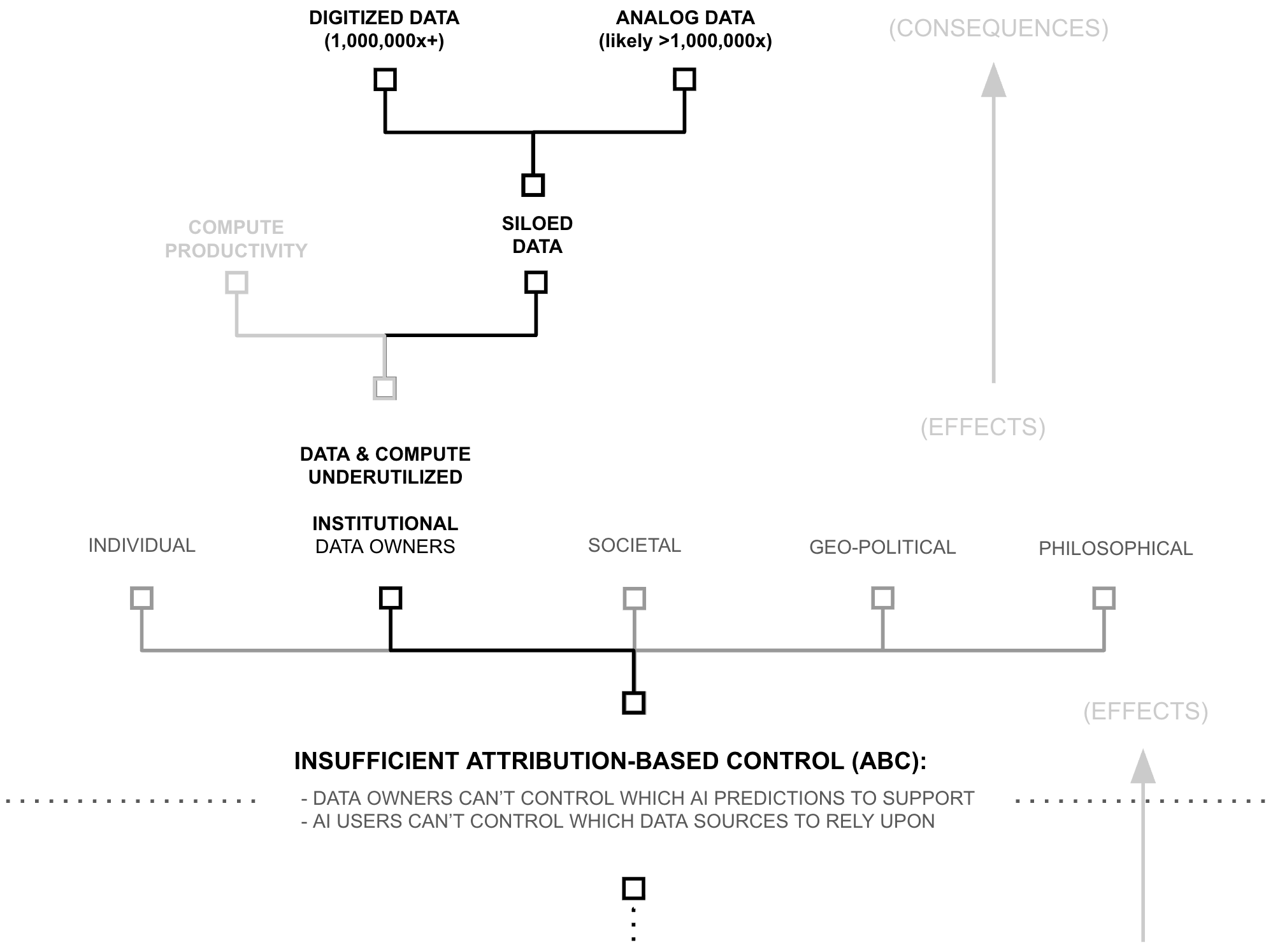

Estimates below suggest that models are trained using less than 1/1,000,000th of the world's data and AI compute productivity. Consequently, following AI's scaling laws, AI models possess capabilities which are insignificant compared to what existing data, compute, and algorithms could create.

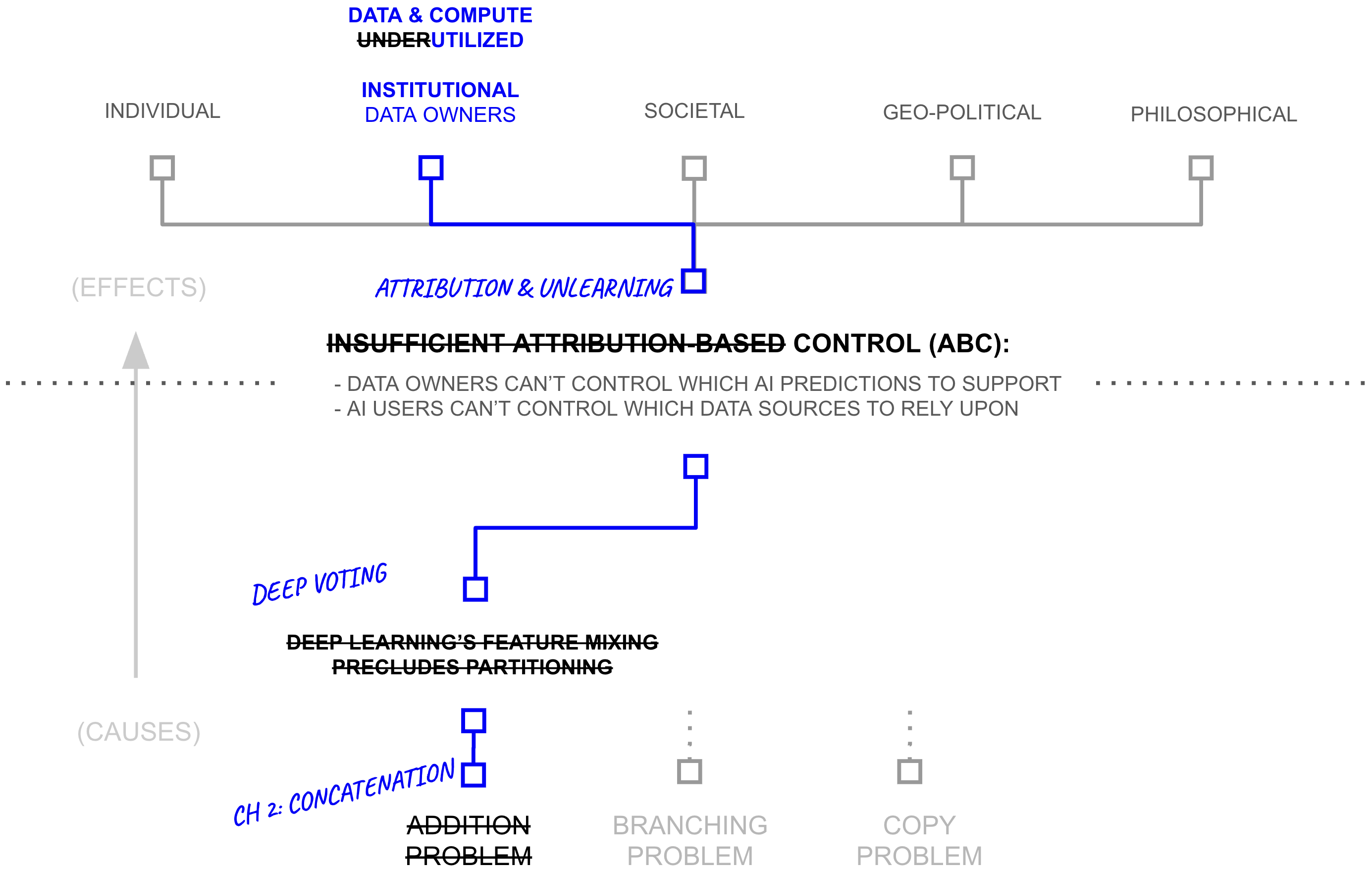

Yet, if AI models (and their capabilities) are the lifeblood of the AI industry, why are data and compute so underutilized? Why is AI capability so constrained? This chapter unpacks the cause of such a drastic resource under-utilization. It begins by linking resource utilization to attribution-based control (ABC). It then breaks attribution-based control into problems with attribution and control, which are themselves underpinned by deep learning's core philosophy of mixing dense features. This mixing is only problematic because of a specific technical choice: the use of addition to update model weights, which erases provenance information during gradient descent.

The chapter then explores alternatives to addition during the training process, revealing a fundamental trade off between three factors: AI capability (driven by unrestricted feature learning), attribution (tracking where features came from), and computational complexity (tracking the path of feature mixing). It proposes a key innovation, a re-purposing of differential privacy for attribution: differential attribution, using the natural boundaries of training documents to identify which concepts must mix freely and vice versa, thereby pushing this Pareto frontier by providing a data-driven approach to balance addition and concatenation.

Building on this insight, the chapter develops a specific form of concatenation to replace addition in key sections of the deep learning training process. This transformation—from deep learning to deep voting—cascades upward through the aforementioned hierarchy of problems, reducing the need for dense feature mixing across data sources, enabling attribution-based control, and unlocking a viable path towards another 6+ orders of magnitude of training data and compute productivity.

The Symptom: Data/Compute Underutilization

As of NeurIPS 2024, leading AI researchers have reported that available compute and data reserves are approaching saturation, creating constraints on both computational resources and pre-training scale. However, this assessment overlooks approximately six orders of magnitude of underutilized compute productivity and siloed data. Rather than absolute scarcity, the industry faces structural problems of data and compute access and productivity.

6+ OOM: Underutilized Training Compute Productivity

The AI industry's computational requirements have driven significant economic and geopolitical consequences, including NVIDIA's rise to become the world's most valuable company, U.S. export restrictions on AI chips to China, and intense competition for latest-generation hardware among startups, enterprises, and major technology firms. However, recent evidence suggests that current AI training and inference processes utilize less than 0.0002% of available compute productivity, indicating that perceived compute scarcity may reflect inefficiency rather than absolute resource limits.

2-3 OOM: Inefficient AI inference

A Library Analogy

Consider a library. When someone asks a librarian about the rules of chess, the librarian doesn't subsequently read every book in the library to find the answer. Instead, they use the catalog system to find a relevant bookshelf, the titles of books on that shelf to find the relevant book, and the table of contents of that book to find the relevant section. This practice stands in stark contrast to how AI systems process information. To make an AI prediction with a model like GPT-3, AI users forward propagate through the entire model and all of its knowledge (i.e., read every book in the library). And in the case of large language models, they don't just do this once per answer, they do this for every token they predict.

DeepMind's RETRO achieves comparable performance to GPT-3 while using 1/25th of the parameters through retrieval from a large-scale vector database. Similarly, Meta's ATLAS demonstrates that models can be reduced to 1/50th their original size while maintaining or exceeding baseline performance through database-augmented inference.

Recent work demonstrates that current architectures contain redundant and underutilized parameters. Guo et al. achieve 5-10x reduction in parameter count through lossless compression while maintaining accuracy:

| Dataset | CIFAR-10 | CIFAR-100 | Tiny ImageNet | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPC | 1 | 10 | 50 | 500 | 1000 | 1 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 1 | 10 | 50 |

| Random | 15.4 | 31.0 | 50.6 | 73.2 | 78.4 | 4.2 | 14.6 | 33.4 | 42.8 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 15.0 |

| DC | 28.3 | 44.9 | 53.9 | 72.1 | 76.6 | 12.8 | 25.2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| DM | 26.0 | 48.9 | 63.0 | 75.1 | 78.8 | 11.4 | 29.7 | 43.6 | - | 3.9 | 12.9 | 24.1 |

| MTT | 46.2 | 65.4 | 71.6 | - | - | 24.3 | 39.7 | 47.7 | 49.2 | 8.8 | 23.2 | 28.0 |

| RCIG | 53.9 | 69.1 | 73.5 | - | - | 39.3 | 44.1 | 46.7 | - | 25.6 | 29.4 | - |

| DATM (Ours) | 46.9 | 66.8 | 76.1 | 83.5 | 85.5 | 27.9 | 47.2 | 55.0 | 57.5 | 17.1 | 31.1 | 39.7 |

| Full Dataset | 84.8 | 56.2 | 37.6 | |||||||||

We adopt RETRO/ATLAS-style parameter efficiency as a conservative lower bound on current compute waste. These results suggest that at least 96-98% of parameters activated during dense inference are unnecessary for individual queries.

6 OOM: Underutilized and Inefficient Compute in AI Learning

A Library Analogy

As before, consider a library. When a library adds or removes a significant number of books to/from their collection, they don't rebuild the entire building and re-print all of their books from scratch, they simply add/remove books, shelves, or rooms. These practices stand in stark contrast to how AI systems process information. To add or remove a significant portion of knowledge from a deep learning system, AI researchers retrain them from scratch (i.e., tear down the entire library, burn all the books, rebuild the library, and re-print all the books from scratch).

Analysis of the largest AI firms reveals that pre-training their most capable models consumes less than 1% of quarterly compute budgets (see table below). Yet these same firms continue expanding computational infrastructure to support larger models, suggesting that remaining compute capacity is allocated to other training activities rather than final model production.

| Model | Organization | Training FLOPs | Parent Org Peak Annual FLOPs | Model/Peak Annual (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini 1.0 Ultra | Google DeepMind | $5.00 \times 10^{25}$ | $3.87 \times 10^{28}$ | 0.129 |

| Claude 3.5 Sonnet | Anthropic | $4.98 \times 10^{25}$ | $2.27 \times 10^{28}$ | 0.220 |

| GPT-4o | OpenAI | $3.81 \times 10^{25}$ | $4.35 \times 10^{28}$ | 0.088 |

| Llama 3.1-405B | Meta AI | $3.80 \times 10^{25}$ | $5.65 \times 10^{28}$ | 0.067 |

| GPT-4 | OpenAI | $2.10 \times 10^{25}$ | $4.35 \times 10^{28}$ | 0.048 |

| Gemini 1.0 Pro | Google DeepMind | $1.83 \times 10^{25}$ | $3.87 \times 10^{28}$ | 0.047 |

| Claude 3 Opus | Anthropic | $1.64 \times 10^{25}$ | $2.27 \times 10^{28}$ | 0.072 |

| Llama 3-70B | Meta AI | $7.86 \times 10^{24}$ | $5.65 \times 10^{28}$ | 0.014 |

| GPT-4o mini | OpenAI | $7.36 \times 10^{24}$ | $4.35 \times 10^{28}$ | 0.017 |

| PaLM 2 | $7.34 \times 10^{24}$ | $3.87 \times 10^{28}$ | 0.019 |

| Category | Computing Power (FLOP/s) | Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cloud/AI Providers | ||

| Meta | $1.79 \times 10^{21}$ | 5.57 |

| Microsoft/OpenAI | $1.38 \times 10^{21}$ | 4.29 |

| Google/DeepMind | $1.23 \times 10^{21}$ | 3.81 |

| Amazon/Anthropic | $7.19 \times 10^{20}$ | 2.23 |

| Consumer Computing | ||

| Smartphones | $7.48 \times 10^{21}$ | 23.23 |

| PC CPUs/GPUs | $2.23 \times 10^{21}$ | 6.92 |

| Game Consoles | $8.64 \times 10^{20}$ | 2.68 |

| Other Cloud/Pre-2023 | $1.65 \times 10^{22}$ | 51.28 |

| Total | $3.22 \times 10^{22}$ | 100.00 |

A Full Picture of Compute Waste

Consider first how an AI system would operate as a librarian. When someone asks about the rules of chess, this librarian doesn't merely consult the games section. Instead, they read every single book in the library. Not just once, they do this for every single query. When this AI librarian needs to add a new book to their collection, they don't simply locate an appropriate shelf using a catalog system. Instead they first read every book in the library, then displace existing books onto the floor to make space, then must re-read everything to determine where to relocate those displaced books. This process repeats, sometimes trillions of times, until the library reaches a new equilibrium.

Now consider how human librarians process information. When someone inquires about chess, they navigate directly to the games section, select a relevant text, and locate the rules. When adding a new book, they utilize the Dewey Decimal system to identify the appropriate shelf and place it there. The process is direct, efficient, and purposeful.

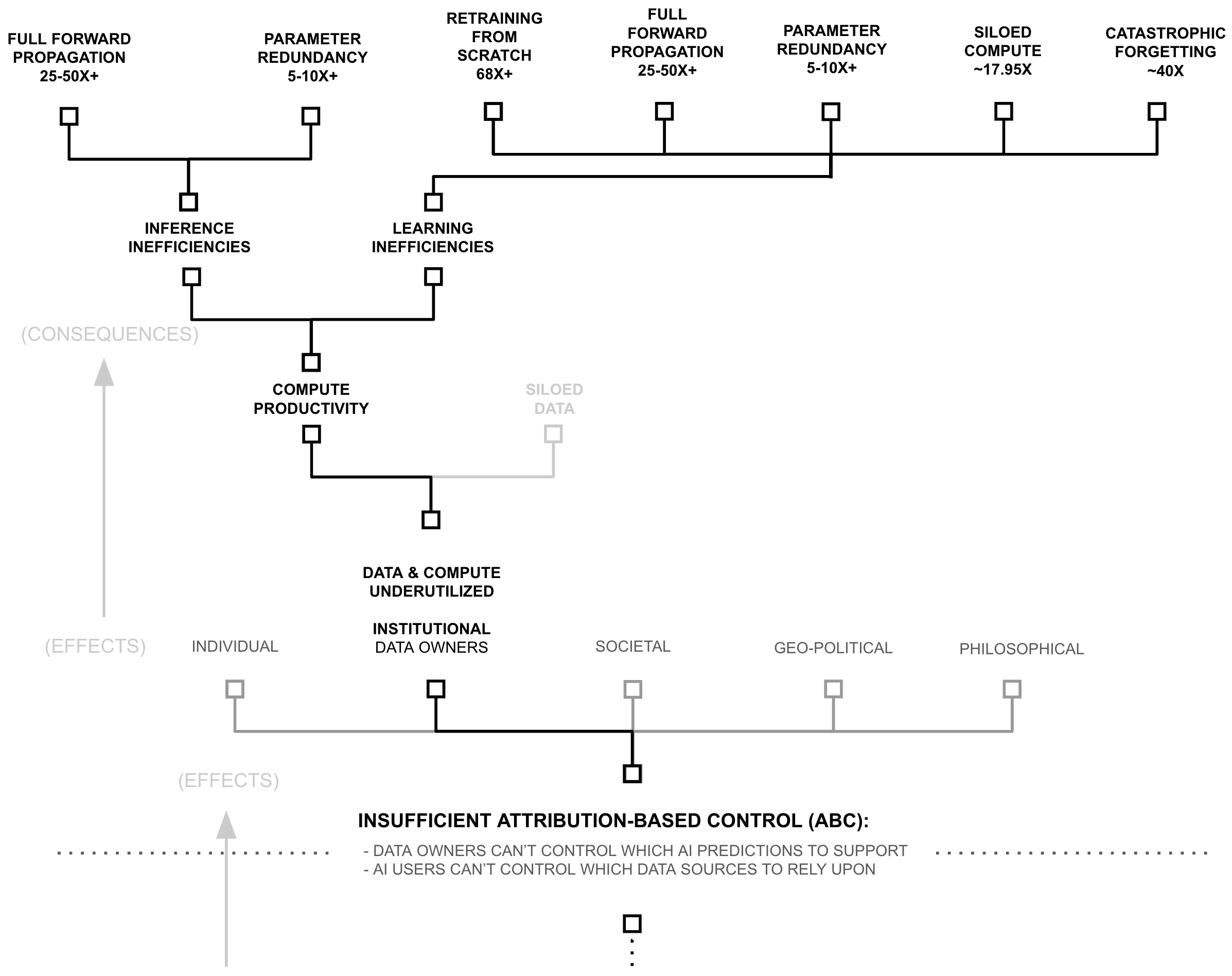

| Inefficiency Type | Range | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Inference Inefficiencies: | ||

| Full Forward Propagation | 25-50x+ | RETRO/ATLAS |

| Parameter Redundancy | 5-10x+ | Compression |

| Catastrophic Forgetting | 40x | Size Heuristic |

| Training Inefficiencies: | ||

| Re-training from Scratch | 68x+ | Industry Analysis |

| Full Forward Propagation | 25-50x+ | RETRO/ATLAS |

| Parameter Redundancy | 5-10x+ | Compression |

| Siloed Compute | ~17.95x | Global Compute |

| Catastrophic Forgetting | 40x | Size Heuristic |

| Combined Effects: | ||

| Inference Total | 5,000-20,000x+ | Multiplicative |

| Training Total | 6,103,000-24,412,000x+ | Multiplicative |

6+ OOM: Siloed Data

Following growing rumors across the AI research community that data is becoming a major bottleneck, OpenAI's former chief scientist, Ilya Sutskever, announced during his test of time award speech at NeurIPS 2024 that data for training AI has peaked, "We've achieved peak data and there'll be no more". However, while this may be true for the AI industry, Ilya's statement does not reflect the reality of what data exists in the world.

A Library Analogy

Consider a world where libraries could only acquire books through anonymous donations left on their doorstep. No matter how many valuable books exist in private collections, university archives, or government repositories, libraries would be limited to what people voluntarily abandon. In such a world, librarians might reasonably conclude they're "running out of books", even while surrounded by vast, inaccessible collections within surrounding businesses and homes.

This mirrors the current state of AI training. When frontier models like GPT-4 (trained on 6.5 trillion tokens), and Qwen2.5-72B (18 trillion tokens), LLama 4 (30 trillion tokens) report hitting data limits, they're really hitting access limits. They're not running out of data, they're running out of data they can freely collect.

The scale of untapped data is staggering:

| Category & Source | Words (T) | Tokens (T) | Rel. Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Web Data | |||

| FineWeb | 11 | 15 | 1.0 |

| Non-English Common Crawl (high quality) | 13.5 | 18 | 1.0 |

| All high quality web text | 45-120 | 60-160 | 4.0-11.0 |

| Code | |||

| Public code | - | 0.78 | 0.05 |

| Private Code | - | 20 | 1.3 |

| Academic & Legal | |||

| Academic articles | 0.8 | 1 | 0.07 |

| Patents | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Books | |||

| Google Books | 3.6 | 4.8 | 0.3 |

| Anna's Archive | 2.8 | 3.9 | 0.25 |

| Every unique book | 16 | 21 | 1.4 |

| US federal court documents | 2 | 2.7 | 0.2 |

| Category & Source | Words (T) | Tokens (T) | Rel. Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media | |||

| Twitter / X | 8 | 11 | 0.7 |

| 29 | 38 | 2.5 | |

| 105 | 140 | 10.0 | |

| Audio (Transcribed) | |||

| YouTube | 5.2 | 7 | 0.5 |

| TikTok | 3.7 | 4.9 | 0.3 |

| All podcasts | 0.56 | 0.75 | 0.05 |

| Private Data | |||

| All stored instant messages | 500 | 650 | 45.0 |

| All stored email | 900 | 1200 | 80.0 |

| Total Human Communication | |||

| Daily | 115 | 150 | 10 |

| Since 1800 | 3,000,000 | 4,000,000 | $10^5$ |

| All time | 6,000,000 | 8,000,000 | $10^5$ |

Stored email and instant messages alone contain over 1,850 trillion tokens, approximately 60 times the largest known training dataset. Daily human communication generates approximately 150 trillion tokens, accumulating to roughly 55 quadrillion tokens annually.

Yet even this vast sea of text represents merely a drop in the ocean of total digital data. While frontier AI models train on curated web scrapes such as Common Crawl (454 TB as of December 2023), the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine alone stores approximately 100 petabytes. Meanwhile, global digital data is projected to reach 180 zettabytes by 2025, six orders of magnitude larger than The Internet Archive and nine orders of magnitude larger than the largest known training datasets.

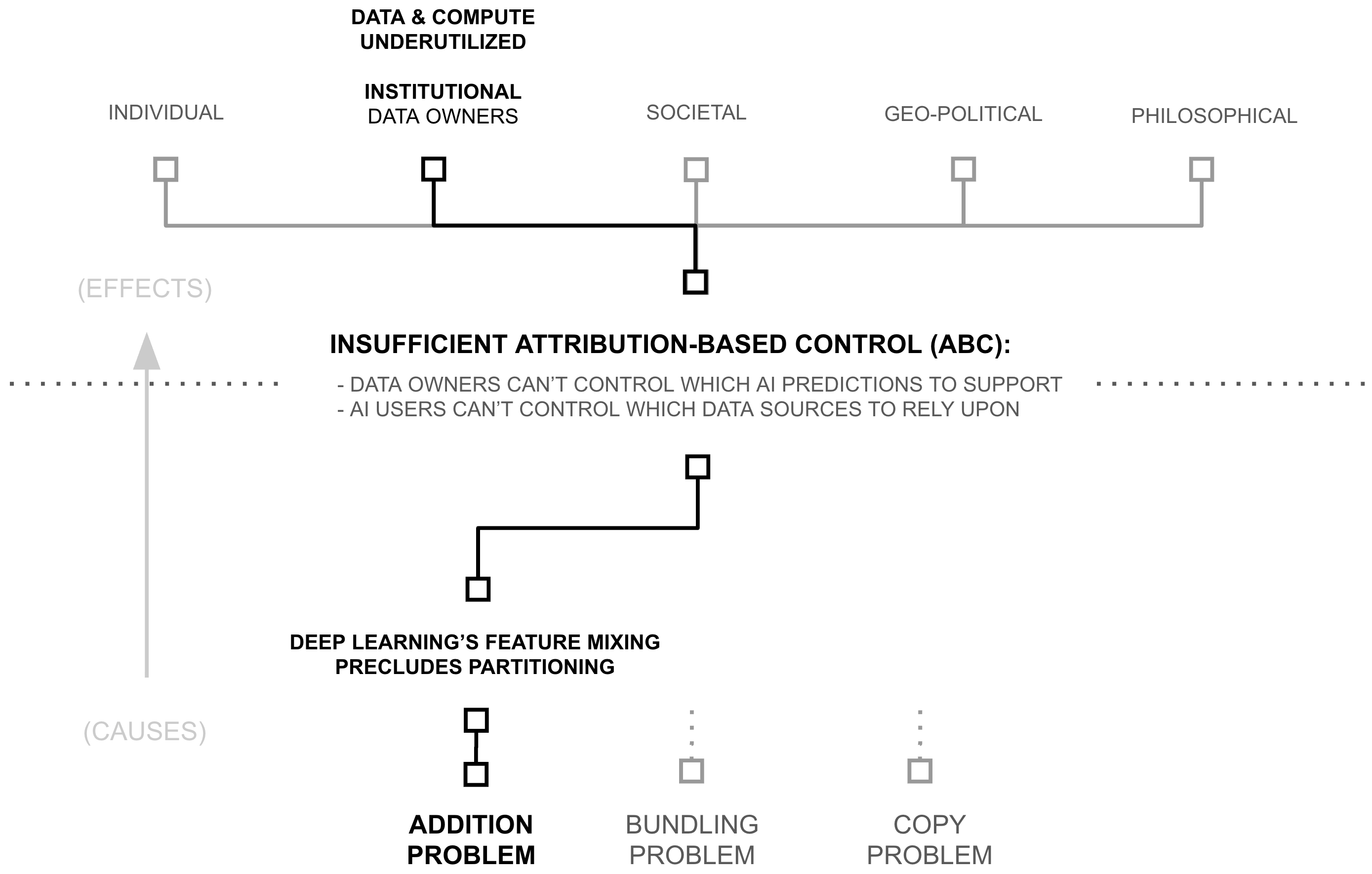

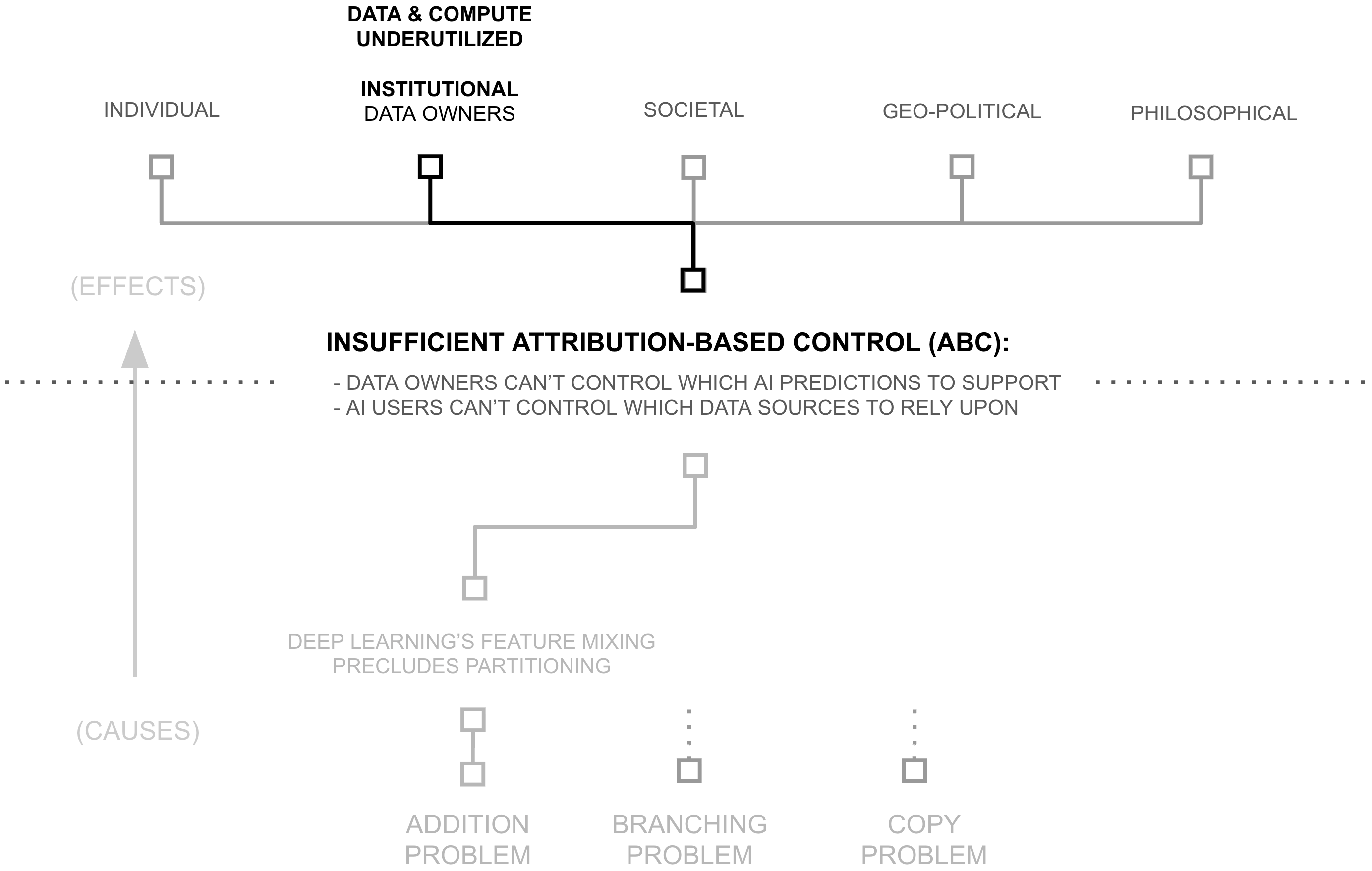

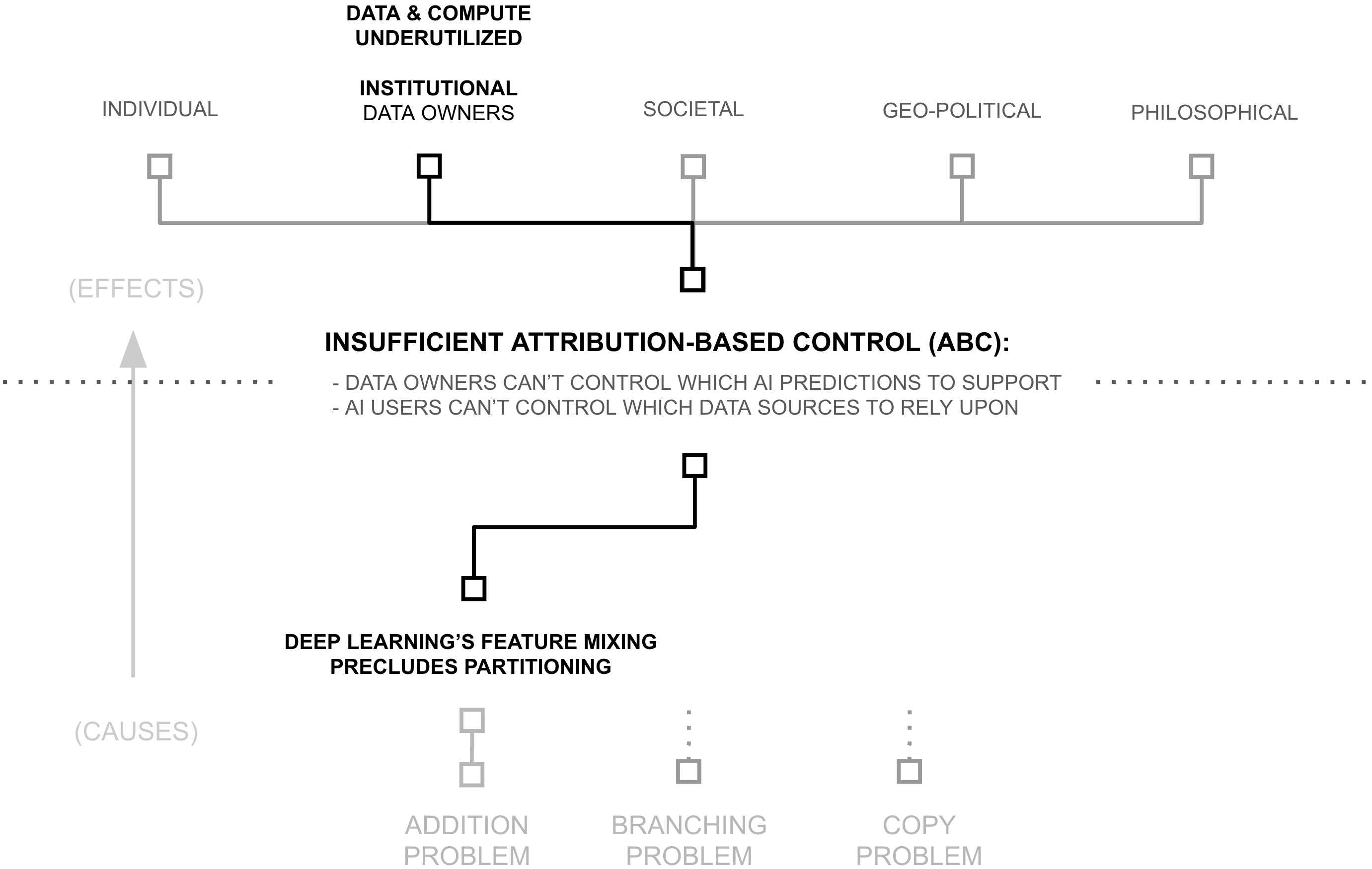

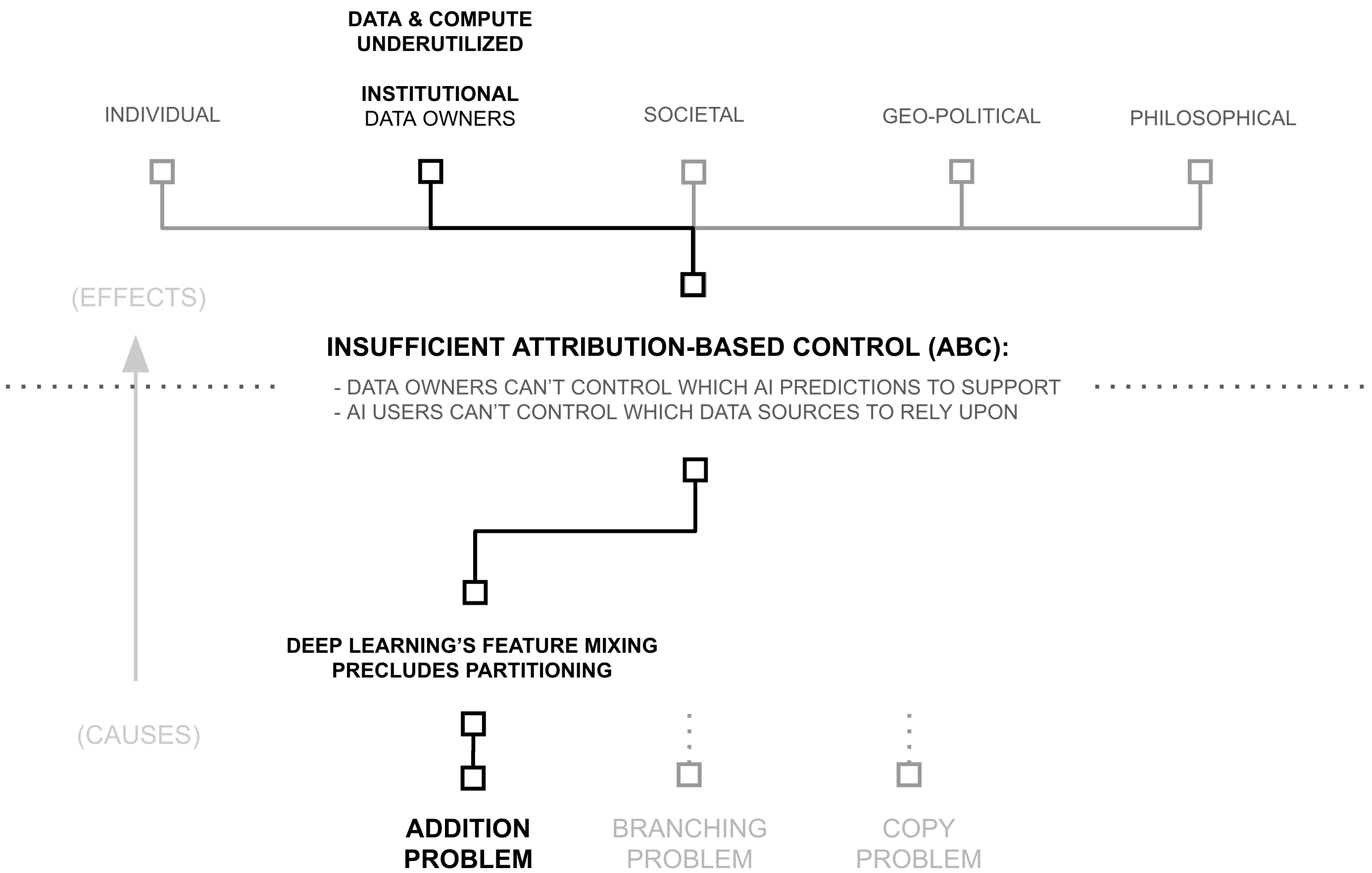

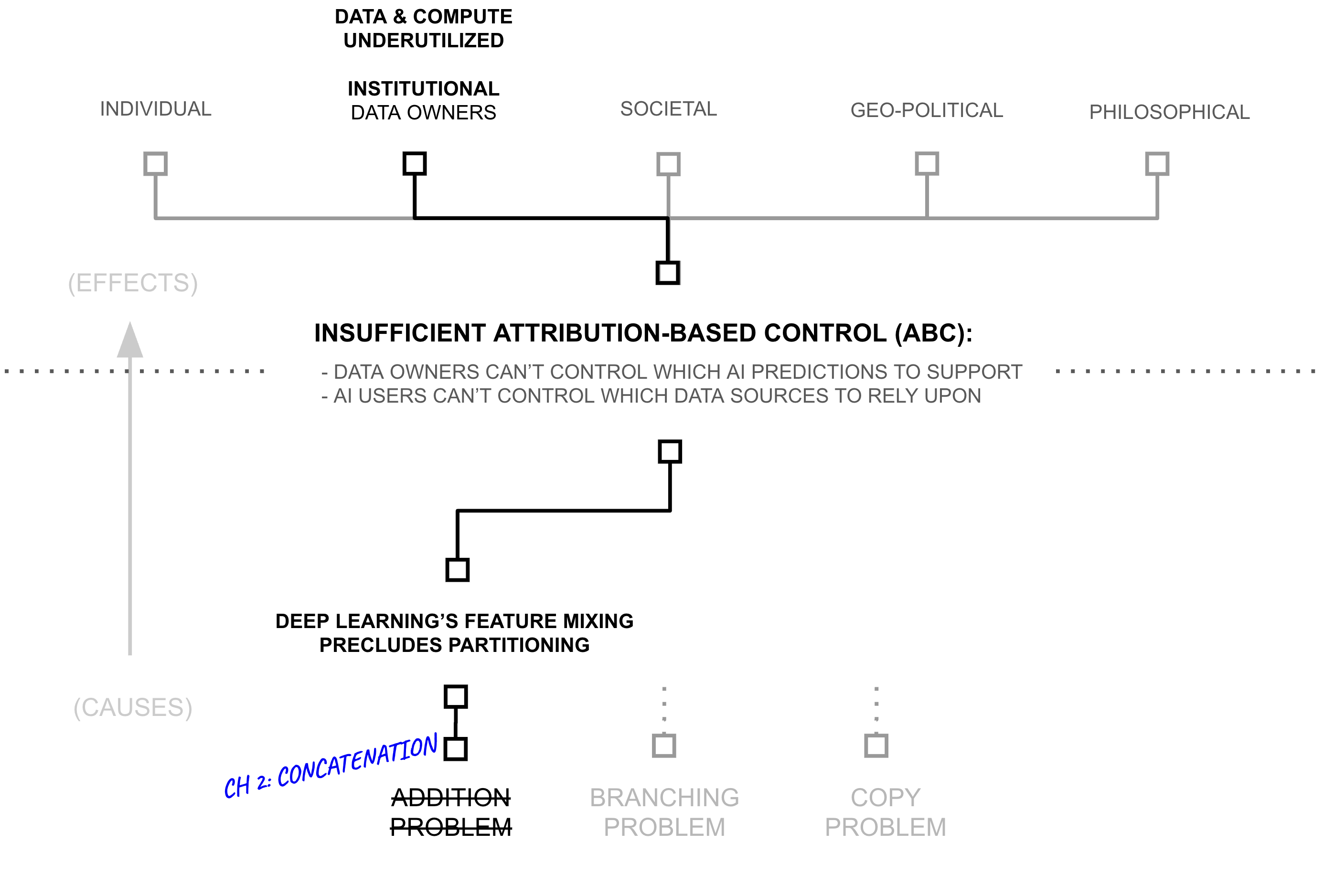

The Search for Root Causes (Three "Whys")

The previous section revealed a paradox: despite widespread beliefs of data and compute scarcity, AI systems access less than one millionth of digital resources. This under-utilization raises a critical question: if more data and compute directly improves AI capabilities through scaling laws, why do AI systems use such a tiny fraction of what's available? The answer lies in a cascade of technical and institutional barriers:

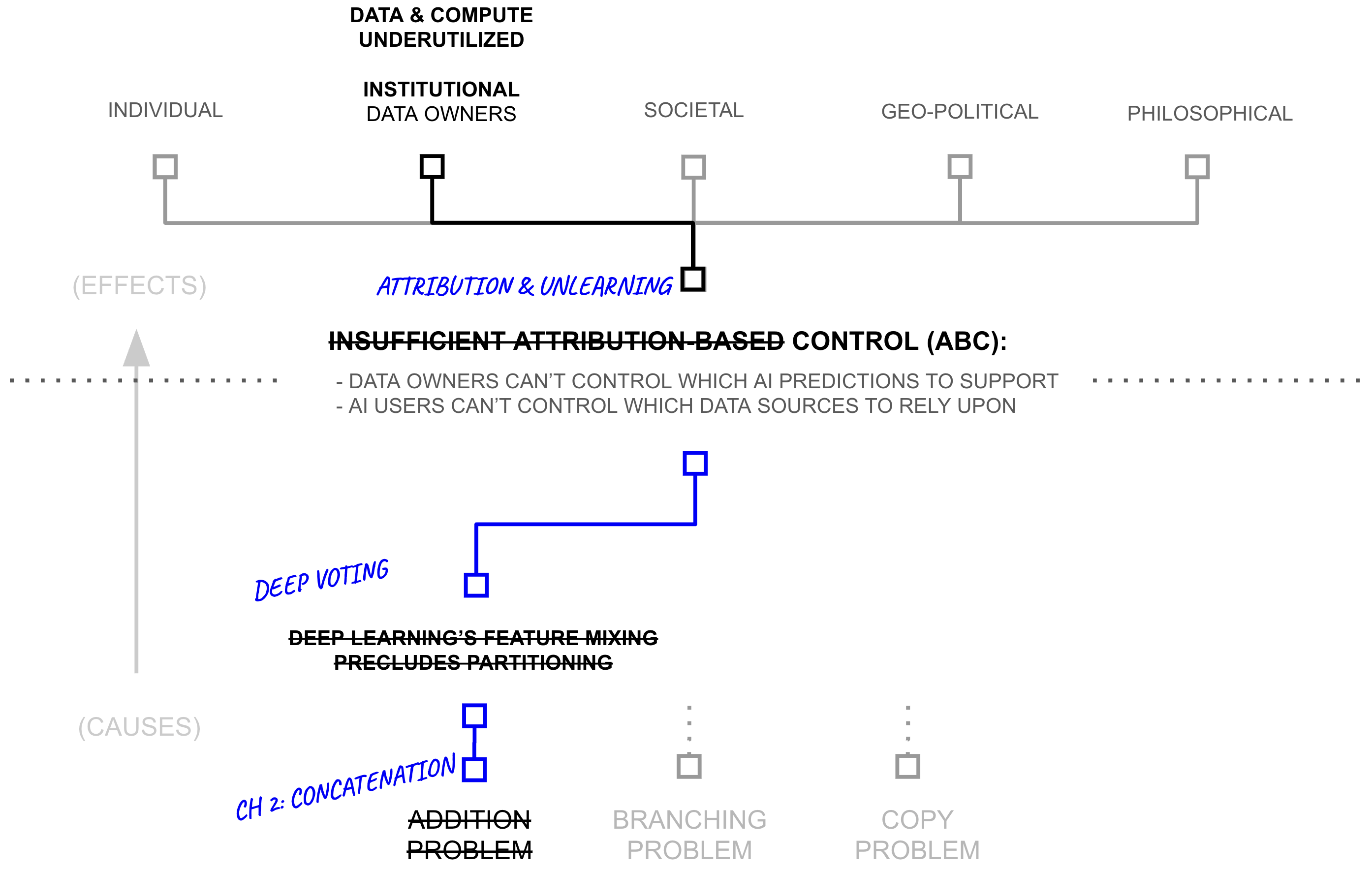

- First Why: Attribution-based Control

- Second Why: Deep Learning's Feature Mixing Precludes Partitioning

- Third Why (Root Cause): Addition of Source-Separable Concepts

First Why: Attribution-based Control

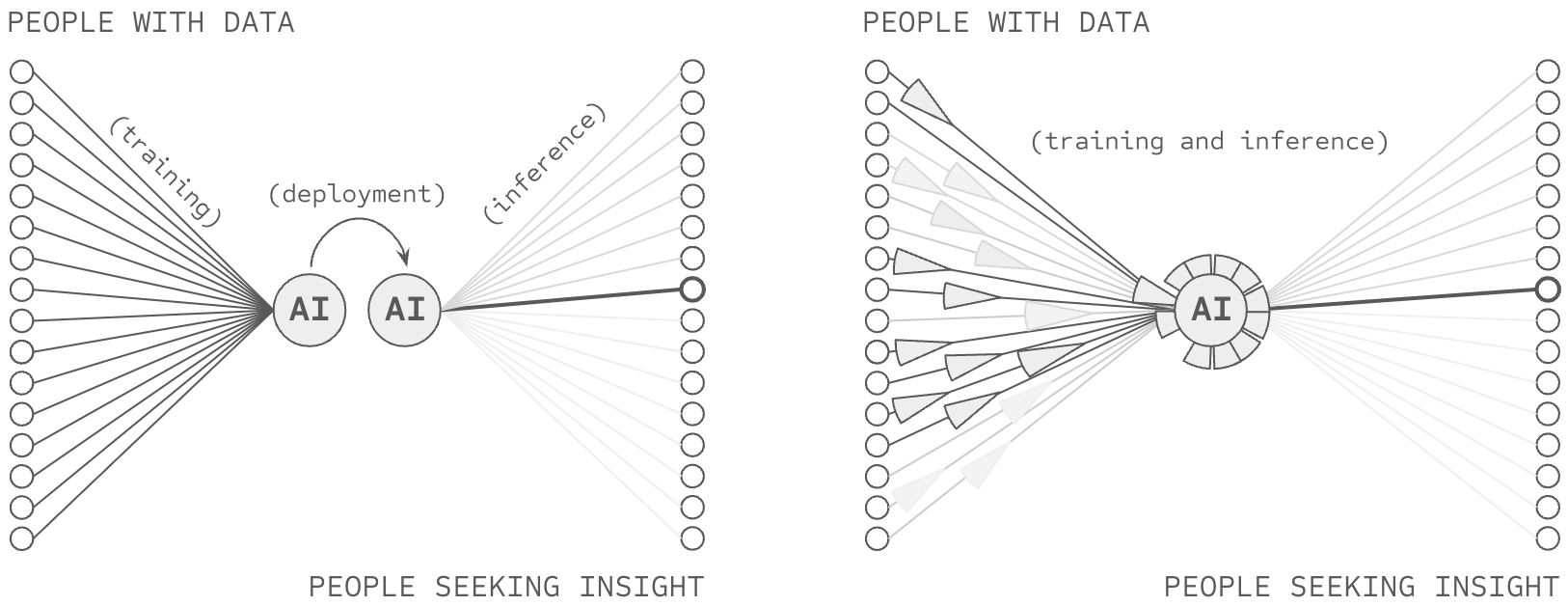

The previous section revealed significant inefficiencies in the training of AI systems: 6+ orders of magnitude in underutilized data and compute. While there may be multiple contributing factors to these constraints, this thesis examines one particular root cause: AI's inability to provide attribution-based control (ABC). An AI model possesses attribution-based control when two properties are true: data sources control which AI predictions they support, AI users control which data sources they rely upon for an AI prediction.

ABC implies certain architectural properties as novel requirements:

- Source-Partitionable Representations: Knowledge within an AI system is partition-able by source

- Rapid Partition Synthesis: Partitions are rapidly synthesize-able during inference

ABC and Compute Productivity (6+ OOM)

ABC would address compute productivity issues along two dimensions: access and learning structure. Regarding structure, successful ABC would necessarily provide a means to structure the learning and representation process, reducing re-training, forward propagation, redundancy, and catastrophic forgetting.

RETRO and ATLAS demonstrate the minimum scale of such a breakthrough. By maintaining source-based partitions through their database architecture, they achieve equal performance while activating only 2-4% of the parameters of similarly performant dense models.

How Failing ABC Siloes Data (6 OOM)

Recall that current AI models can only train on data they can access. Consequently, AI models almost certainly train on less than 1/1,000,000th of the digitized information in the world because they cannot access the other 99.9999%, which remains hidden amongst the world's 360 million companies, 8+ billion citizens, etc.

Successful ABC would necessarily enable one particularly compelling form of data sharing. The ability for a data source to decide which AI predictions to support is (almost tautologically) the ability for a data source to enable uses while averting mis-uses. One could argue that truly successful ABC would constitute an incentive shift attracting all of the world's data to be pulled into at least some AI predictions.

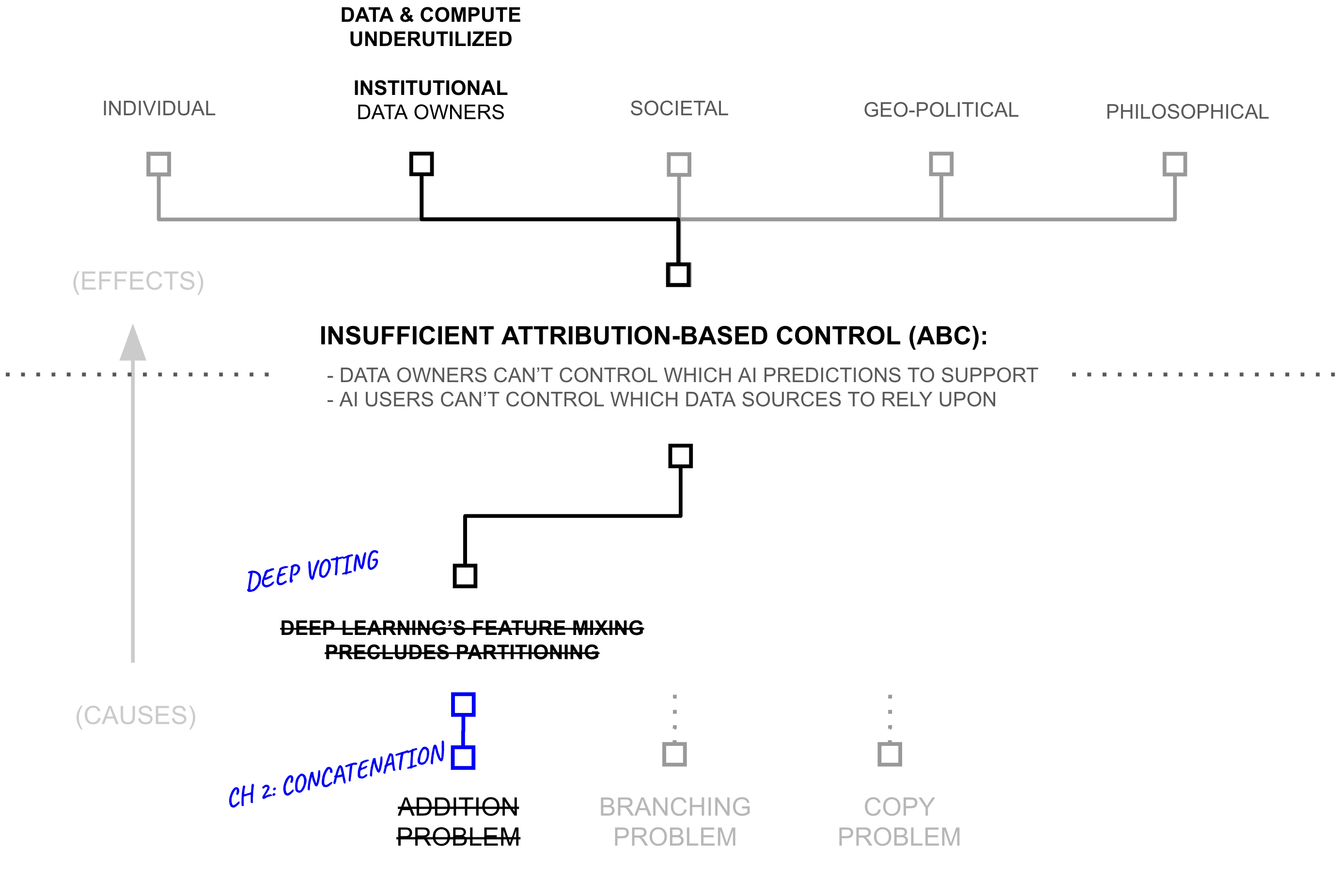

Second Why: Deep Learning's Feature Mixing Precludes Partitioning

The previous section revealed how solving attribution-based control would necessarily enable massive data and compute gains in AI systems. Yet this raises a deeper question: why do current AI systems fail to maintain attribution in the first place? The answer lies in deep learning's foundational premise: algorithms should learn everything from scratch through layers of (largely) unrestricted feature mixing on raw data.

This commitment to unrestricted learning manifests in how neural networks fundamentally process information. Through operations that combine and mix information at every step (from layer computations to weight updates to knowledge accumulation) neural networks create increasingly complex representations of patterns in their training data. While this flexibility enables powerful pattern recognition, it creates a fundamental problem: features become stored in a disorganized, obfuscated way within the deep learning model... a black box.

A Library Analogy

Consider a library wherein all of the books have had their covers removed, their table of contents erased, and their chapters torn out and shuffled amongst all the books. Consequently, when someone wants to answer a specific question, they have to read through the entire library searching for relevant information for their query.

Deep learning stores information in a similar way, with so-called distributed representations spreading concepts across many neurons... each of which is unlabeled (i.e. "hidden"). Far from an accident, this form of learning is at the center of deep learning's core philosophy, the unrestricted learning of dense, hidden features.

Third Why (Root Cause): Addition of Source-Separable Concepts

The previous section revealed how deep learning's feature mixing precludes the partitioning required for attribution-based control. Yet this raises our final "why": what makes this mixing fundamentally irreversible? The answer lies in deep learning's most basic mathematical operation: addition.

Addition might seem like an implementation detail, but it fundamentally prevents recovering source information. When values combine through addition, the result does not uniquely determine its inputs—multiple distinct source combinations produce identical outputs:

Non-Injectivity of Addition

Addition is not injective: for any sum y, there exist infinitely many distinct pairs (x1, x2) and (x'1, x'2) such that x1 + x2 = y = x'1 + x'2 where (x1, x2) ≠ (x'1, x'2).

Concatenation vs Addition

Concatenation preserves sources:

"1" ⊕ "6" = "16"

"2" ⊕ "5" = "25"

(distinct inputs → distinct outputs)

Addition erases them:

1 + 6 = 7

2 + 5 = 7

(distinct inputs → identical outputs)

When partitions are known, concatenation of numbers is injective; different inputs produce different outputs, allowing source recovery. Addition is not; the output 7 could arise from 1+6, 2+5, 3+4, 0+7, or infinitely many other combinations. This non-injectivity is the mechanism through which deep neural networks erase attribution information: once gradients from different sources are summed into shared parameters, no function of those parameters can recover which sources contributed what information.

The Root Problem: Without the ability to track sources through training, we cannot provide the attribution that ABC requires. Without attribution, we cannot enable the partitioned sharing and use of data and compute that could unlock orders of magnitude more AI resources. Addition itself blocks the very data and compute gains described earlier in this chapter.

Third Hypothesis: Concatenating Along Natural Boundaries Enables Attribution

The previous sections revealed how addition in deep learning creates a fundamental barrier to attribution. Yet examining why addition fails suggests a testable hypothesis: can we significantly reduce the use of addition, perhaps swapping it with concatenation?

Some information patterns appear ubiquitously: basic rules of grammar that structure language, logical operations that appear in reasoning, morphological patterns which make up words, edges and corners in images, etc. Such dense patterns suggest unrestricted mixing through addition may be appropriate for a core subset of features. Their ubiquity also makes attribution less critical; they represent shared computational tools rather than source-specific claims about the world. While perhaps not formally stated, noted researcher Andrej Karpathy recently suggested a similar concept when referring to a future LLM "cognitive core":

The race for LLM "cognitive core"—a few billion param model that maximally sacrifices encyclopedic knowledge for capability. It lives always-on and by default on every computer as the kernel of LLM personal computing. Its features are slowly crystalizing:

- Natively multimodal text/vision/audio at both input and output.

- Matryoshka-style architecture allowing a dial of capability up and down at test time.

- Reasoning, also with a dial. (system 2)

- Aggressively tool-using.

- On-device finetuning LoRA slots for test-time training, personalization and customization.

- Delegates and double checks just the right parts with the oracles in the cloud if internet is available.

It doesn't know that William the Conqueror's reign ended in September 9 1087, but it vaguely recognizes the name and can look up the date. It can't recite the SHA-256 of empty string as e3b0c442..., but it can calculate it quickly should you really want it.

What LLM personal computing lacks in broad world knowledge and top tier problem-solving capability it will make up in super low interaction latency (especially as multimodal matures), direct / private access to data and state, offline continuity, sovereignty ("not your weights not your brain"). i.e. many of the same reasons we like, use and buy personal computers instead of having thin clients access a cloud via remote desktop or so.

— Andrej Karpathy[link]

In contrast, perhaps most information is encyclopedic and appears sparsely: specific facts about the world, domain expertise in particular fields, claims made by individual sources, etc. The capital of France, the rules of chess, statistics about pizza... each appears in distinct contexts with limited overlap.

A key insight of this chapter is that techniques from privacy-preserving machine learning, particularly differential privacy (DP), provide a principled way to measure and control which features benefit from dense mixing versus sparse representation. Differential privacy quantifies how much a model's outputs depend on any individual training example:

(ε, δ)-Differential Privacy

A randomized mechanism $\mathcal{M}: \mathcal{D} \to \mathcal{R}$ satisfies (ε, δ)-differential privacy if for all adjacent datasets $D, D' \in \mathcal{D}$ (differing in one example) and all subsets of outputs $S \subseteq \mathcal{R}$:

$\Pr[\mathcal{M}(D) \in S] \leq e^\epsilon \cdot \Pr[\mathcal{M}(D') \in S] + \delta$

where small ε indicates strong privacy—outputs barely depend on any individual example.

The parameter ε provides a quantitative measure of individual example influence on outputs. This same measure can serve three distinct control objectives:

Three Regimes of Influence Control

- Privacy (constrain influence): Enforce εe < τmin for all examples

- Measurement (track influence): Compute εe for each example

- Attribution (ensure influence): Enforce εe > τmax for specified examples

Second Hypothesis: Deep Voting with Intelligence Budgets

The previous section revealed how privacy mechanisms might naturally separate dense from sparse information patterns. Yet this theoretical insight raises a practical question: how do we actually implement the measurement and control regimes we defined? The definitions in the previous section assumed worst-case bounds (requiring that ε constraints hold for all pairs of neighboring datasets). But attribution-based control requires the opposite: not uniform bounds across all sources, but source-specific control where each source can have different influence levels matching different stakeholder needs.

From Worst-Case to Individual Differential Privacy

Standard differential privacy enforces worst-case bounds across all possible pairs of neighboring datasets. Consider a dataset where most individuals' data appears in common patterns, but one individual has highly unique data. Worst-case differential privacy must constrain the entire mechanism based on that one outlier, reducing utility for everyone—even though the mechanism only ever operates on the actual dataset, not all possible datasets. Individual differential privacy provides a more nuanced approach by focusing privacy guarantees on the actual dataset rather than all possible datasets:

Individual Differential Privacy

Given a dataset $D$, a response mechanism $\mathcal{M}(\cdot)$ satisfies ε-individual differential privacy (ε-iDP) if, for any dataset $D'$ that is a neighbor of $D$ (differing in one example), and any $S \subset \text{Range}(\mathcal{M})$:

$\exp(-\epsilon) \cdot \Pr[\mathcal{M}(D') \in S] \leq \Pr[\mathcal{M}(D) \in S] \leq \exp(\epsilon) \cdot \Pr[\mathcal{M}(D') \in S]$

The crucial difference from standard DP: $D$ refers to the actual dataset being protected, while $D'$ ranges over $D$'s neighbors. Standard DP requires indistinguishability for any pair of neighbors; individual DP requires indistinguishability only between the actual dataset and its neighbors.

From Individual Privacy to Individual Attribution

Just as we extended standard differential privacy to define attribution regimes in the previous section, we can extend individual differential privacy to define individual attribution. The key insight remains the same: privacy and attribution are opposite ends of the same ε spectrum, now applied to the actual dataset rather than worst-case bounds.

Individual Differential Privacy vs. Attribution

For a mechanism $\mathcal{M}$, actual dataset $D$, and threshold $\tau > 0$:

- Individual Privacy: Enforce $\epsilon < \tau$ for all neighbors $D'$ of $D$, guaranteeing that any individual's data in the dataset cannot be distinguished through its influence on outputs.

- Individual Measurement: Compute $\epsilon$ for the actual dataset, enabling quantification of influence without enforcing bounds.

- Individual Attribution: Enforce $\epsilon > \tau$ for the actual dataset, guaranteeing that individuals in the actual dataset have measurable influence on outputs.

From Examples to Sources: Group Differential Privacy

But attribution-based control requires more than individual-level bounds, it requires source-level control. Individual differential privacy protects single examples in the actual dataset, but data sources typically contribute many examples. Consider a medical AI trained on data from 100 hospitals: each hospital contributes thousands of patient records. ABC needs to measure and control influence at the hospital level, not just the individual patient level. The differential privacy literature addresses this through group differential privacy, which extends privacy guarantees from individuals to groups of records:

Group Differential Privacy

A randomized mechanism $\mathcal{M}: \mathcal{D} \to \mathcal{R}$ satisfies ε-group differential privacy for groups of size $k$ if for all datasets $D, D'$ differing in at most $k$ records and all subsets of outputs $S \subseteq \mathcal{R}$:

$\Pr[\mathcal{M}(D) \in S] \leq e^\epsilon \cdot \Pr[\mathcal{M}(D') \in S]$

We can combine group differential privacy with individual differential privacy to obtain source-level control calibrated to the actual dataset. When we partition a dataset by sources $D = \bigcup_{s \in S} D_s$, we treat each source as a group and apply individual DP at the group level:

Source-Level Individual Differential Privacy

Given a dataset $D$ partitioned by sources $D = \bigcup_{s \in S} D_s$, a response mechanism $\mathcal{M}(\cdot)$ satisfies $\epsilon_s$-individual differential privacy for source $s$ if, for any dataset $D'$ differing from $D$ only in source $s$'s data (i.e., $D' = D_{-s} \cup D'_s$ where $|D'_s| = |D_s|$), and any $S \subset \text{Range}(\mathcal{M})$:

$\exp(-\epsilon_s) \cdot \Pr[\mathcal{M}(D') \in S] \leq \Pr[\mathcal{M}(D) \in S] \leq \exp(\epsilon_s) \cdot \Pr[\mathcal{M}(D') \in S]$

From Source-Level Privacy to Source-Level Attribution

Just as individual DP extends to attribution regimes (privacy, measurement, attribution), source-level individual DP extends to source-level attribution. We can quantitatively measure each source's influence on the actual dataset:

Source-Level Individual Differential Attribution

Let $\mathcal{A}$ be a randomized algorithm and let $D$ be a dataset partitioned by sources $D = \bigcup_{s \in S} D_s$. For any source $s$ and prediction $f$, the individual differential attribution of source $s$ on function $f$ is:

$\text{Attribution}_\alpha(s, f) = D_\alpha^\leftrightarrow(\mathcal{A}(D)\|\mathcal{A}(D^{-s})) = \max\{D_\alpha(\mathcal{A}(D)\|\mathcal{A}(D^{-s})), D_\alpha(\mathcal{A}(D^{-s})\|\mathcal{A}(D))\}$

where $D_\alpha$ is the Rényi divergence of order $\alpha$, $D^{-s} = D \setminus D_s$ represents the dataset with source $s$ removed, and $\mathcal{A}(D)$ represents the output distribution of algorithm $\mathcal{A}$ on dataset $D$.

This measures each source's attribution relative to the actual dataset $D$ by quantifying how predictions change when that specific source is included versus excluded. This enables the diverse source-level control ABC requires.

Intelligence Budgets: Implementing Individual Source Control

This source-level individual attribution measure enables a practical control mechanism: intelligence budgets. Rather than simply measuring influence after the fact, we can actively control how much each source influences predictions through architectural routing decisions.

Intelligence Budgets via Forward Pass Weighting

The model has two types of parameterized functions:

$g_s(\cdot; \Theta_{\text{semantic}}[s])$: source-specific function for source $s$

$f(\cdot; \Theta_{\text{syntactic}})$: shared function across all sources

Information flows through two stages:

Stage 1 (Semantic): $s_s = g_s(x_s; \Theta_{\text{semantic}}[s])$

Stage 2 (Syntactic): $h(x) = f\left([x_1, \ldots, x_{|S|}, \gamma[1] \cdot s_1, \ldots, \gamma[|S|] \cdot s_{|S|}]; \Theta_{\text{syntactic}}\right)$

where $\gamma[s] \in [0,1]$ is a per-source scaling weight and $[\cdot]$ denotes concatenation of all inputs.

The intelligence budget $B(s)$ bounds source $s$'s influence:

$\text{Attribution}_\alpha(s, h) \leq B(s)$

Setting $\gamma[s] \approx 0$ enforces small $B(s)$ (privacy regime) by preventing semantic contributions. Setting $\gamma[s] \approx 1$ allows large $B(s)$ (attribution regime) by preserving semantic identity.

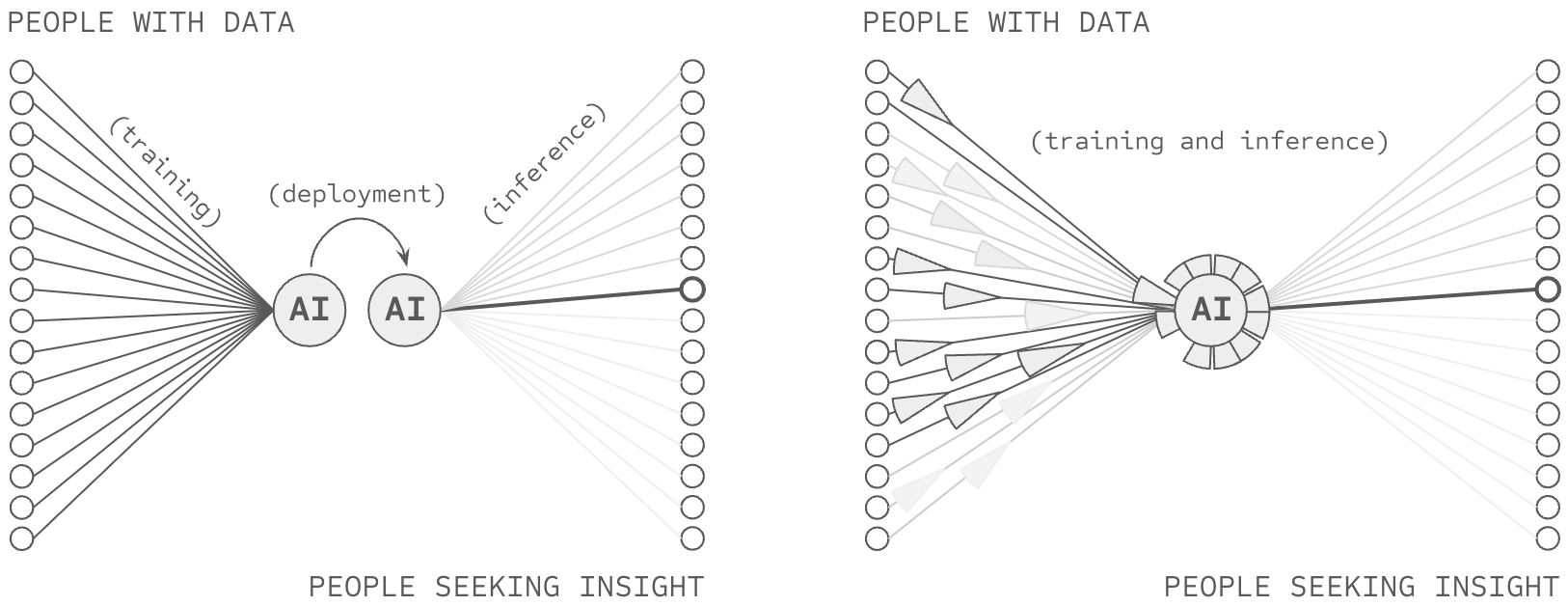

From Concatenation and IDP to Deep Voting

The deep voting framework reveals a two-dimensional spectrum in machine learning architectures by introducing a second control parameter $\lambda \in [0,1]$ that governs the overall balance between semantic and syntactic capacity:

Capacity Allocation (λ)

The parameter λ determines what fraction of total model capacity is allocated to each function:

$|\Theta_{\text{syntactic}}| = \lambda \cdot |\Theta_{\text{total}}|$

$\sum_{s} |\Theta_{\text{semantic}}[s]| = (1-\lambda) \cdot |\Theta_{\text{total}}|$

where $|\Theta|$ denotes parameter count.

Deep Voting Analogy: Individual Differential Privacy via Adaptive Filtering

Feldman and Zrnic's individual differential privacy framework provides a concrete example of intelligence budgets implemented through adaptive filtering rather than architectural routing.

Architecture: Their approach uses $\lambda = 1$ (pure syntactic processing) with all capacity in shared parameters $\Theta_{\text{syntactic}}$. No semantic section exists ($\Theta_{\text{semantic}}[s] = \emptyset$), meaning all sources contribute only through raw inputs: $h(x) = f([x_1, \ldots, x_n]; \Theta_{\text{syntactic}})$ where $f$ adds Gaussian noise for privacy.

Intelligence Budgets via Filtering: Rather than controlling $\gamma[s]$ continuously, they implement binary filtering. At each time step $t$, compute the individual privacy loss $\rho_t^{(i)} = \frac{\alpha \|\bar{g}_t(X_i)\|_2^2}{2\sigma^2}$ where $\bar{g}_t(X_i)$ is the clipped gradient. Source $i$ remains active while $\sum_{j=1}^t \rho_t^{(i)} \leq B$, then gets dropped (equivalent to setting $\gamma[i] = 0$ for all future steps).

Key Insight: The intelligence budget $B(i)$ is implicitly determined by realized gradient norms. For Lipschitz functions with coordinate sensitivity $L_i$, the bound becomes $B(i) \approx \frac{\alpha L_i^2 \|\phi(X_i)\|^2}{2\sigma^2}$. Sources with small gradients (low sensitivity) can participate longer before exceeding their budget.

Contrast with Deep Voting: Feldman & Zrnic achieve privacy (small ε) by dropping high-influence examples entirely, routing all remaining examples through privacy-constrained shared processing. Deep voting generalizes this by: (1) introducing a semantic section ($\lambda < 1$) that preserves source identity, (2) allowing continuous control ($\gamma[s] \in [0,1]$) rather than binary drop/keep decisions, and (3) enabling attribution regime where large ε is desirable. Individual DP represents the special case where $\lambda = 1$, $\gamma[s] \in \{0,1\}$ (binary), and all sources demand privacy.

Adaptive Composition: The Feldman & Zrnic result on adaptive composition with data-dependent privacy parameters ($\sum_t \rho_t^{(i)} \leq B \Rightarrow (\alpha, B)$-RDP) directly parallels our intelligence budget composition: both handle the challenge that influence parameters depend on previous outputs, enabling provable bounds even under adaptive computation.

With these mechanisms in place, we can return to the implications of such a system for providing attribution-based control: the potential to dramatically increase the amount of data and compute available for training AI systems. By providing clear mechanisms for measuring source influence ($\text{Attribution}_\alpha(s, h)$), bounding influence when needed ($\gamma[s] = 0$ for privacy), and guaranteeing influence when required ($\gamma[s] = 1$ for attribution), deep voting might enable the safe use of orders of magnitude more training data.

A Library Analogy

Consider a library wherein all of the books have had their covers removed, their table of contents erased, and individual sentences on each page torn out into their own strips. Now imagine that each word in each strip is converted into a number "aardvark = 1", "abernathe = 2", and so forth. And then imagine that each of these strips from the whole library is shuffled around, and groups of strips are placed back in the coverless books. Yet, instead of each strip being glued in place, it is first combined with many other strips, adding their respective numbers together. Consequently, when someone wants to answer a specific question, they have to read through the entire library searching for relevant information for their query—first by converting their query into numbers and then attempting to match it to numbers found in the books.

Following the analogy, differential attribution ensures that each strip of numbers remains separated (instead of added) into each other strip, preserved within the same book as before, partitioning information in a way which might be indexed by source (or topic). It further provides a staff of librarians who know how to read relevant information and synthesize them, each according to a topic that librarian happens to be familiar with. Taken together, a customer of a library can leverage one librarian to index into the appropriate shelf, identify the right book, and the right snippets of that book, and then ask a subset of the staff of librarians who are experts on that topic to properly interpret those snippets.

First Hypothesis: ABC and 6+ Orders of Magnitude more Data/Compute

The deep voting framework reveals a two-dimensional spectrum in machine learning architectures. Consider how different parameter settings affect the model's behavior:

At (λ,γ) = (1,0), we find pure deep learning with maximum compression. These systems, like GPT-4, use only shared parameters with basic bounds on attribution. At (λ,γ) = (0,1), we find pure partition-based learning, like federated systems, which maintain group privacy but limit cross-source learning. At (λ,γ) = (0,0), we find pure source-specific learning systems like k-nearest neighbors.

The stakes are significant. If deep voting succeeds, it could unlock another 6+ orders of magnitude of training data and compute productivity. If it fails, we may remain constrained by the fundamental limitations of current architectures.

Empirical Evidence: Does the Pareto-Tradeoff Move?

The First Crack: RETRO and ATLAS

Recent architectures challenge baseline tradeoffs. RETRO outperforms GPT-3 on the Pile (0.670 vs 0.811 bits-per-byte) while using only 7.5B parameters compared to GPT-3's 175B:

| Subset | 7B Baseline | GPT-3 | Jurassic-1 | Gopher | 7.5B RETRO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| arxiv | 0.742 | 0.838 | 0.680 | 0.641 | 0.714 |

| books3 | 0.792 | 0.802 | 0.835 | 0.706 | 0.653 |

| dm_mathematics | 1.177 | 1.371 | 1.037 | 1.135 | 1.164 |

| freelaw | 0.576 | 0.612 | 0.514 | 0.506 | 0.499 |

| github | 0.420 | 0.645 | 0.358 | 0.367 | 0.199 |

| gutenberg_pg_19 | 0.803 | 1.163 | 0.890 | 0.652 | 0.400 |

| hackernews | 0.971 | 0.975 | 0.869 | 0.888 | 0.860 |

| nih_exporter | 0.650 | 0.612 | 0.590 | 0.590 | 0.635 |

| opensubtitles | 0.974 | 0.932 | 0.879 | 0.894 | 0.930 |

| philpapers | 0.760 | 0.723 | 0.742 | 0.682 | 0.699 |

| pile_cc | 0.771 | 0.698 | 0.669 | 0.688 | 0.626 |

| pubmed_abstracts | 0.639 | 0.625 | 0.587 | 0.578 | 0.542 |

| pubmed_central | 0.588 | 0.690 | 0.579 | 0.512 | 0.419 |

| stackexchange | 0.714 | 0.773 | 0.655 | 0.638 | 0.624 |

| ubuntu_irc | 1.200 | 0.946 | 0.857 | 1.081 | 1.178 |

| uspto_backgrounds | 0.603 | 0.566 | 0.537 | 0.545 | 0.583 |

| Average | 0.774 | 0.811 | 0.705 | 0.694 | 0.670 |

This constitutes a 25x reduction in parameter count while achieving superior performance and maintaining clear attribution paths through its retrieval mechanism.

ATLAS demonstrates similar gains: 25-50x parameter efficiency improvements while maintaining or exceeding baseline performance. Both systems achieve these results through a fundamental architectural shift: rather than compressing all knowledge into dense parameters, they maintain explicit connections to source documents through retrieval.

Federated RAG systems demonstrate concurrent improvements in attribution and performance:

| Task | Federated RAG Accuracy (%) | Baseline RAG Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Task 1 | 78 | 70 |

| Task 2 | 82 | 75 |

| Task 3 | 74 | 68 |

| Task 4 | 88 | 80 |

| Task 5 | 81 | 76 |

Deep Voting: Formalizing the Pattern

These architectures (RETRO, ATLAS, PATE, federated RAG, and Git Re-Basin) share a common technical mechanism: they replace addition operations during training with concatenation, deferring synthesis until inference time. We formalize this pattern as deep voting.

Deep voting addresses the addition problem that blocks access to 6+ orders of magnitude of data and compute. By preserving source attribution through concatenated representations while enabling cross-source learning through shared components, deep voting architectures demonstrate that the baseline tradeoffs between attribution, efficiency, and performance reflect architectural choices rather than fundamental constraints.

However, solving the addition problem reveals a deeper challenge: the copy problem. Even if one achieved perfect attribution through deep voting, data sources cannot enforce how their contributions are used because whoever possesses a copy of the model retains unilateral control. Chapter 2 addresses this challenge, introducing techniques that enable attribution-based control rather than mere attribution-based suggestions.

References

- (2020). Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. arXiv:2001.08361.

- (2022). Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models. arXiv:2203.15556.

- (2024). OpenAI cofounder Ilya Sutskever says the way AI is built is about to change. The Verge.

- (2022). Improving language models by retrieving from trillions of tokens. ICML 2022, 2206–2240.

- (2023). Atlas: Few-shot Learning with Retrieval Augmented Language Models. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 24, 1–43.

- (2023). Towards lossless dataset distillation via difficulty-aligned trajectory matching. arXiv:2310.05773.

- (2024). Data on Notable AI Models. epoch.ai/data/notable-ai-models.

- (2016). Deep Learning. MIT Press.

- (2018). Measuring Catastrophic Forgetting in Neural Networks. AAAI 2018.

- (2024). How much LLM training data is there, in the limit? Educating Silicon.

- (2013). Building high-level features using large scale unsupervised learning. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence.

- (2012). ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. NeurIPS 2012.

- (2014). Visualizing and Understanding Convolutional Networks. ECCV 2014.

- (2014). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press.

- (2006). Calibrating noise to sensitivity in private data analysis. TCC 2006.

- (2016). Deep Learning with Differential Privacy. CCS 2016.

- (2020). Individual Privacy Accounting via a Renyi Filter. arXiv:2008.11193.

- (2018). Scalable Private Learning with PATE. ICLR 2018.

- (2018). Federated Learning with Non-IID Data. arXiv:1806.00582.

- (2022). Git Re-Basin: Merging Models modulo Permutation Symmetries. arXiv:2209.04836.

- (2024). A Survey of Machine Unlearning. arXiv:2209.02299.

- (1997). Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Computation, 9(8), 1735–1780.