Attribution-Based Control in AI Systems

University of Oxford

Abstract

Many of AI's risks in areas like privacy, value alignment, copyright, concentration of power, and hallucinations can be reduced to the problem of attribution-based control (ABC) in AI systems, which itself can be reduced to the overuse of addition, copying, and branching within gradient descent. This thesis synthesizes a handful of recently proposed techniques in deep learning, cryptography, and distributed systems, revealing a viable path to reduce addition, copying, and branching; provide ABC; and address many of AI's primary risks while accelerating its benefits by unlocking 6+ orders of magnitude more data, compute, and associated AI capability.

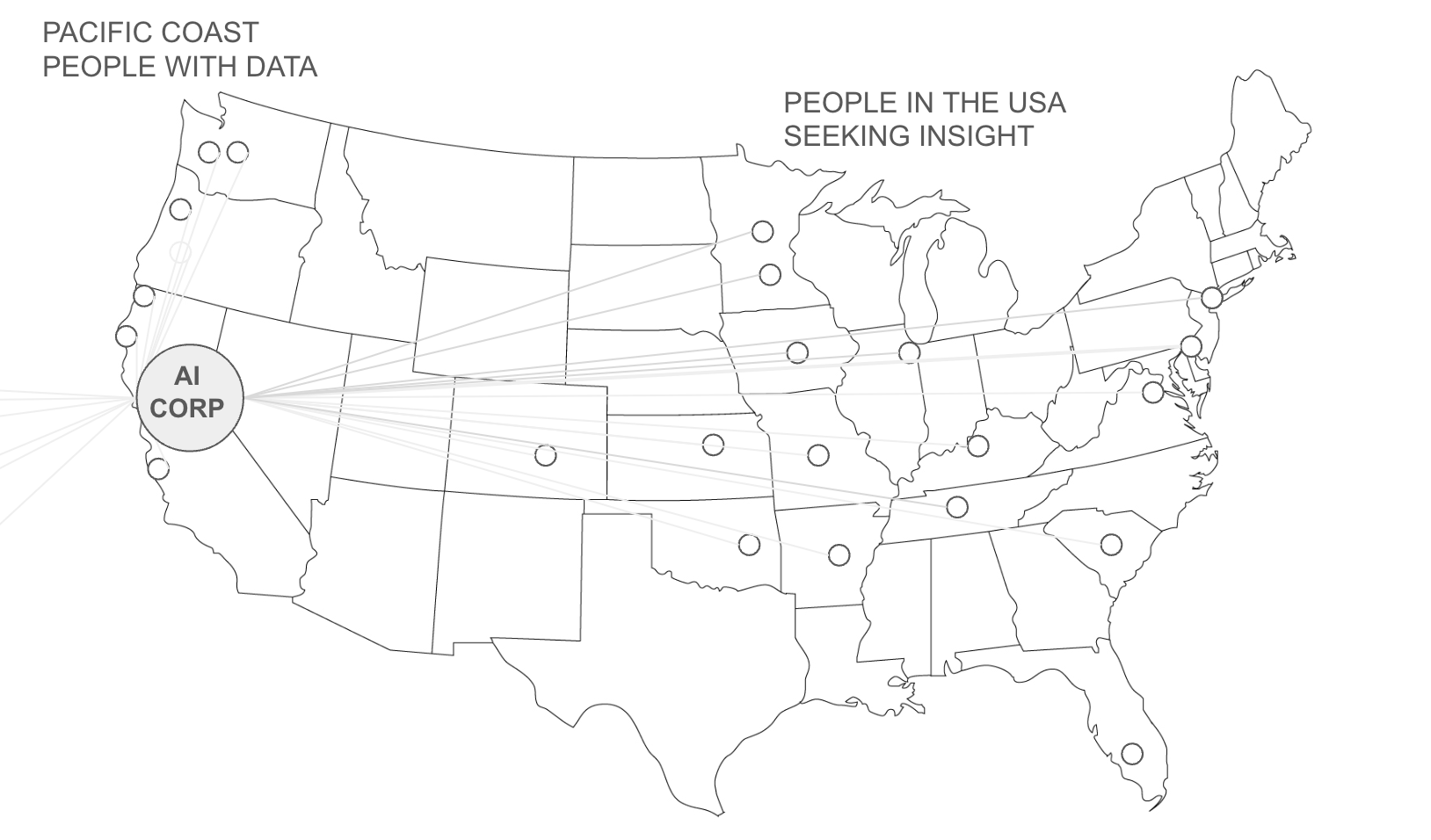

While AI systems learn from data, AI users cannot know or control which data points inform which predictions because AI lacks attribution-based control (ABC). Consequently, AI draws upon sources whose exact integrity cannot be verified. And when AI draws upon incomplete or problematic sources, it struggles with hallucinations, disinformation, value alignment, and a greater collective action problem: while an AI model in a democratic nation is as capable as the amount of data and compute a company can collect, an AI model in an authoritarian nation may become as capable as the amount of data and compute an entire nation can collect. Consequently, to win the AI race, democratic nations must either embrace the centralization of data and compute (i.e., centralize AI powered decision making across their society) or relinquish AI advantage to nations who do.

This thesis describes how these problems stem from a single technical source: AI's over-reliance on copying, addition, and branching operations during training and inference. By synthesizing recent breakthroughs in cryptography, deep learning, and distributed systems, this thesis proposes a new method for AI with attribution-based control. When fully bloomed, this breakthrough can enable each AI user to control which data sources drive an AI's predictions, and enable an AI's data sources to control which AI users they wish to support, transforming AI from a centralized tool that produces intelligence to a communication tool that connects people.

Taken together, this thesis describes an ongoing technical shift, driven by the hunt for 6-orders of magnitude more data and compute, and driven by value alignment to powerful market and geo-political forces of data owners and AI users, which is transforming AI from a tool of central intelligence into something radically different: a communication tool for broad listening.

The Problem of Attribution-Based Control (ABC)

Definition: Attribution-Based Control

An AI system provides attribution-based control (ABC) when it enables a bidirectional relationship between two parties:

- Data Sources: control which AI outputs they support with AI capability, and calibrate the degree to which they offer that support.

- AI Users: control which data sources they rely upon for AI capability, and calibrate the degree to which they rely on each source.

They negotiate which sources are leveraged and how much capability to create.

At the present moment, AI systems do not comprehensively enable AI users to know or control which data sources inform which AI outputs (or vice versa) which is to say they do not offer attribution-based control (ABC). While RAG and similar algorithms might appear to offer inference-level control, AI systems fail to provide formal guarantees that data provided to the input of a model is truly being leveraged to create the output. Taken together, with respect to data provided during pre-training, fine-tuning, or inference, AI systems do not offer ABC.

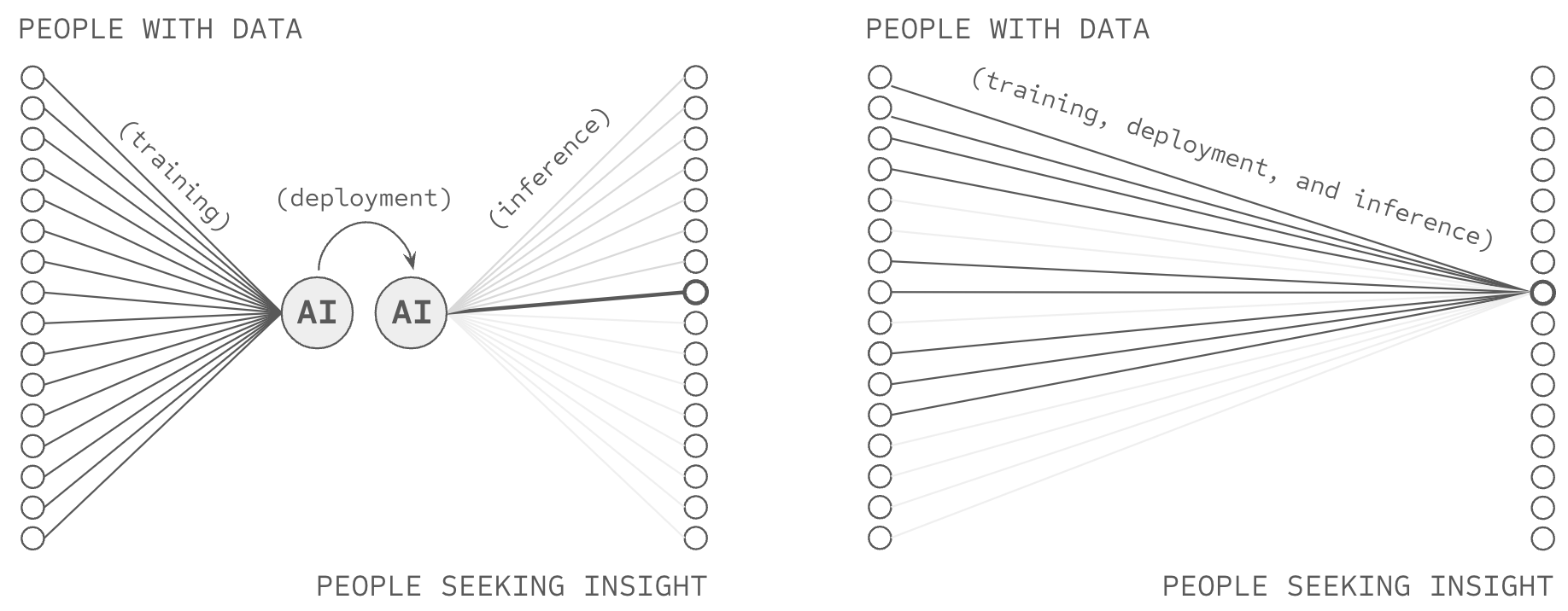

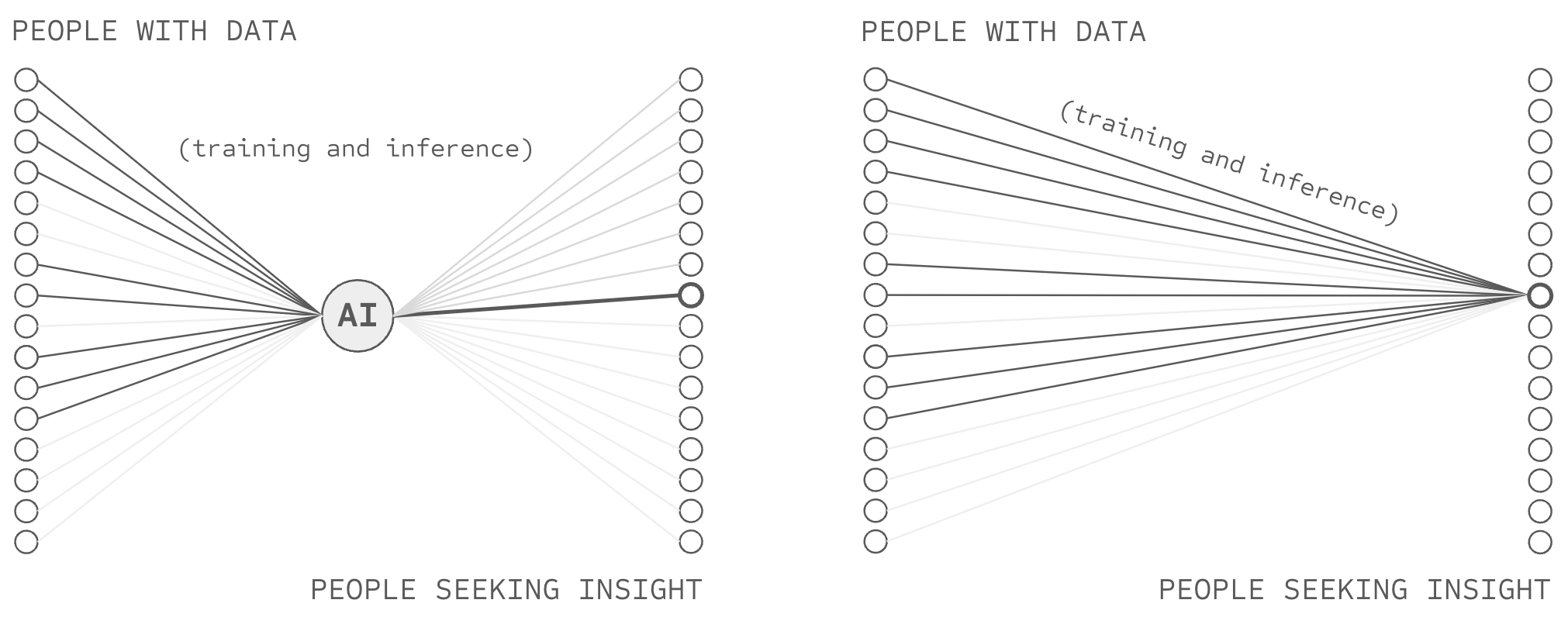

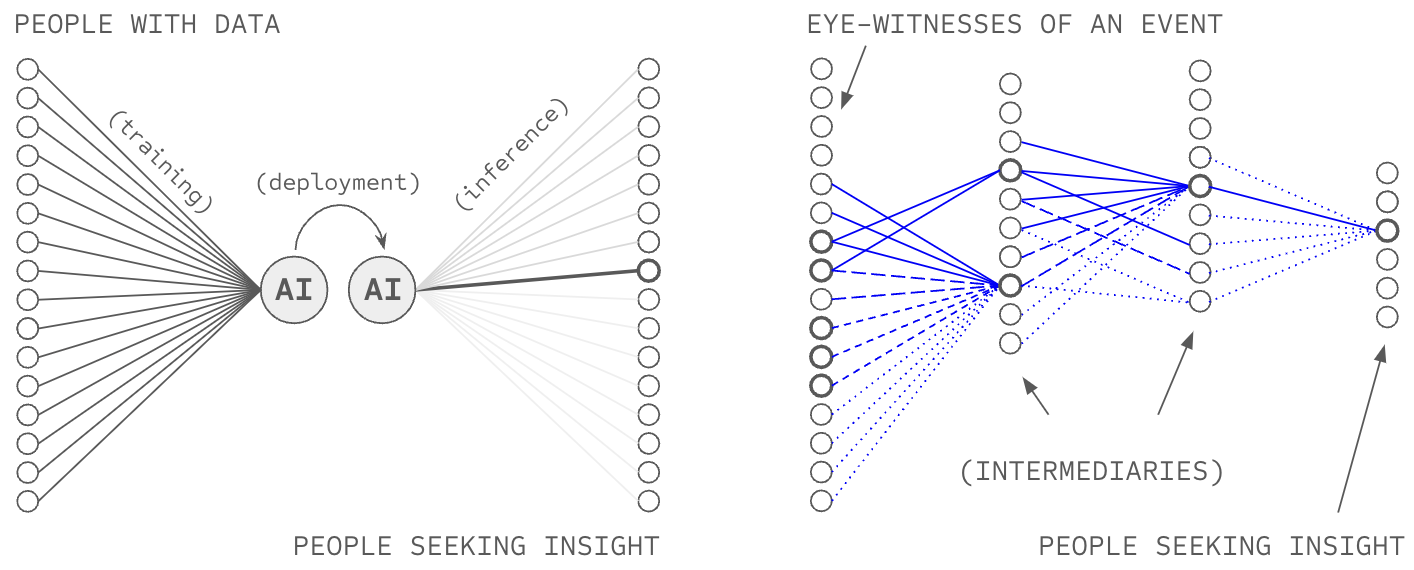

Consequently, AI is conceived of (by people in the world) as a system that gains intelligence by harvesting information about the world, as opposed to a communication technology which enables billions of people with information to aid billions seeking insights. In the same way, an AI model is conceived of as the asset which produces intelligence, instead of merely as a temporary cache of information making its way from sources to users. If AI were a telephone, it would be one without buttons, and its users would believe they are talking to the phone itself, as opposed to talking with people through the phone.

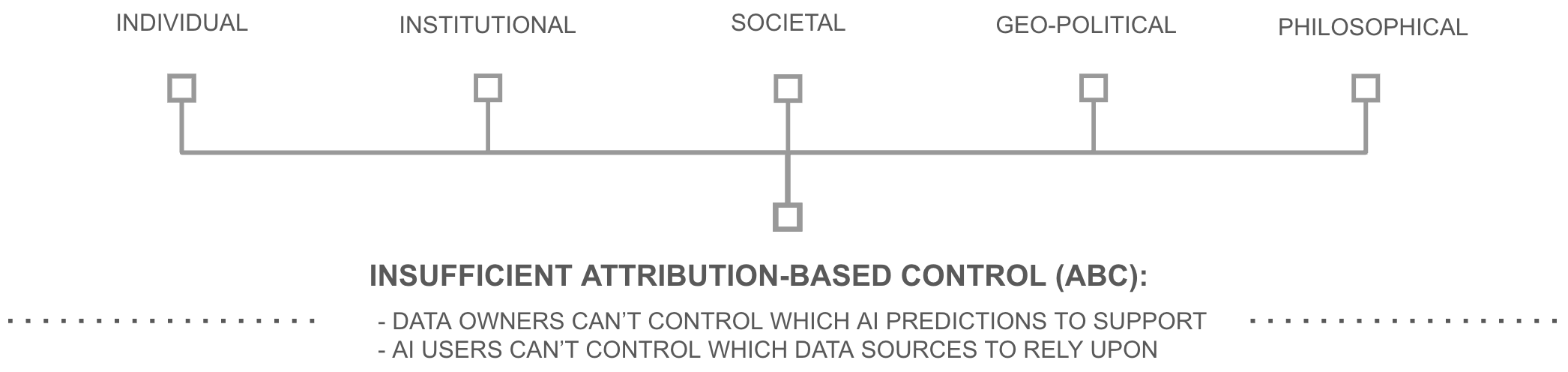

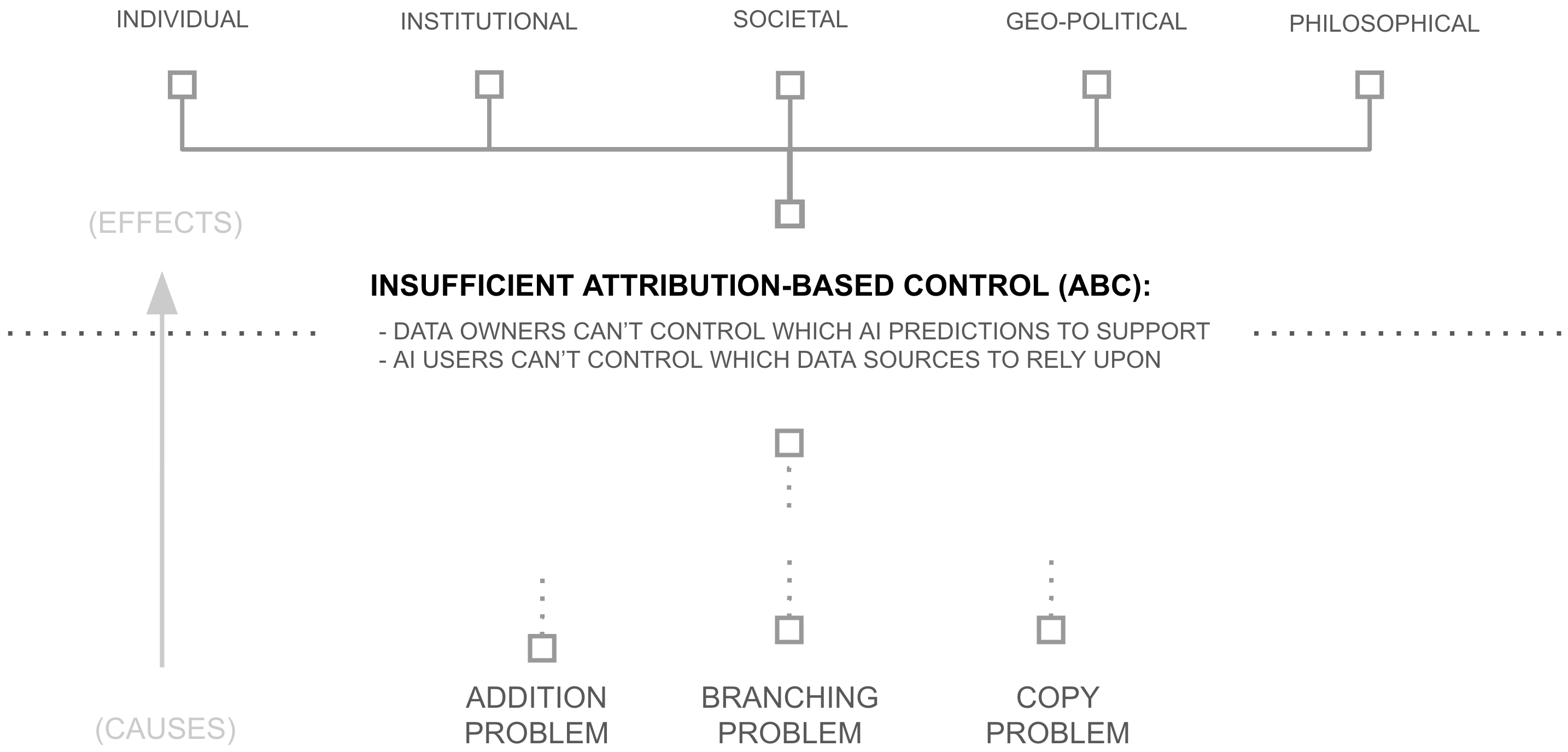

This design decision triggers a cascade of consequences, consequences which are felt uniquely at each level of society: individual, institutional, societal, and geo-political. And as a result, each level of society is incubating deep desires for something more than today's AI has to offer. The next four subsections survey this increasing demand for ABC in AI by surveying the felt consequences of the lack of ABC in AI.

Individual Consequences

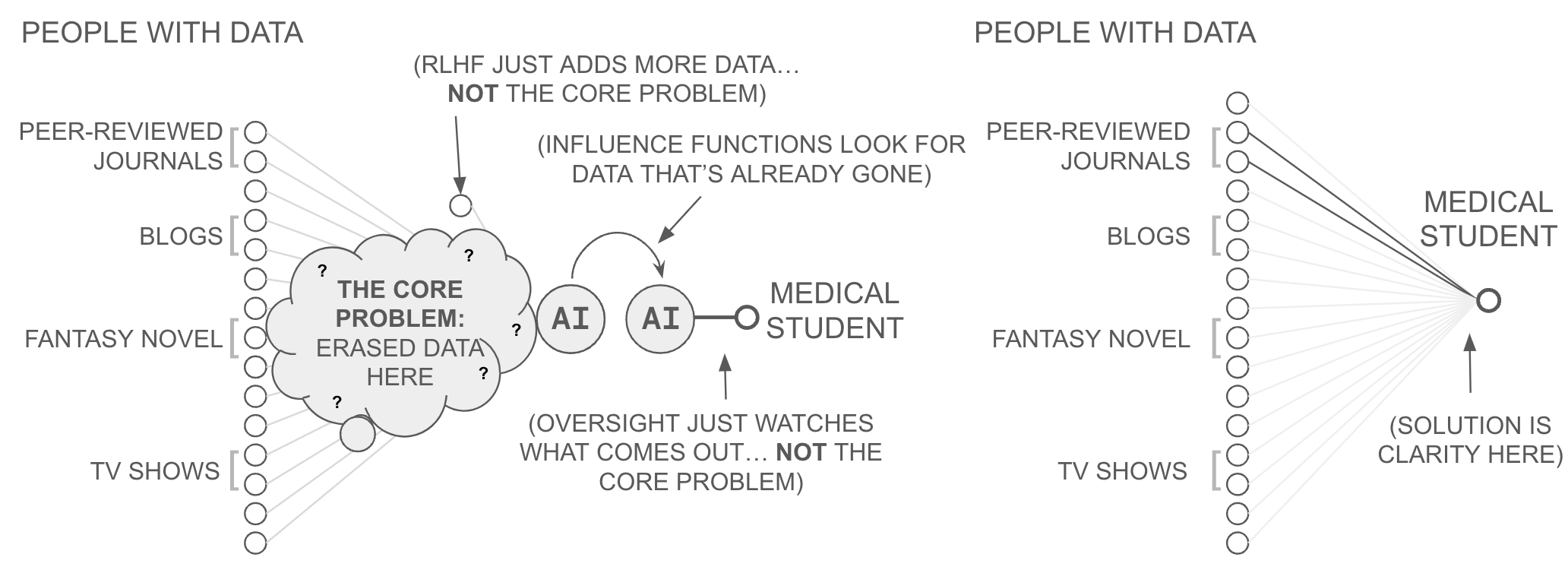

The lack of ABC presents AI users with a basic authenticity problem, discussed publicly using phrases like hallucination, deepfake, and disinformation. When an AI generates a response, users often cannot verify its sources; unlike a Google search where one can examine original documents. Consider a medical student using AI to research rare diseases. They cannot tell whether an AI's detailed symptom description comes from high-quality sources (e.g., peer-reviewed journals) or less qualified sources. Meanwhile, the researchers who authored medical papers feeding the AI lose control over how their work is used, dis-incentivizing them to share information. This mutual blindness creates the opportunity for hallucination and disinformation.

Hallucination: To see ABC's contribution to the problem of hallucination, consider the mechanics of an AI hallucination. In some cases, an AI model makes a prediction regarding a subject either not properly covered in its training data or prompt, or not properly recalled during inference. But since an AI model's predictions are necessarily based on data, the AI will attempt to use insights from less related documents to generate a plausible-sounding response: a hallucination. Yet, because of a lack of ABC, the AI user has little ability to spot an AI model sourcing from such unqualified documents, or to make adjustments to ensure the AI's prediction is properly sourced. The AI user, for example, has no ability to say, "I queried this AI model about Java development, but I notice it's relying upon data sources about Indonesian coffee cultivation instead of programming language documentation." Instead, the AI user merely sees the output and wonders, "Is this AI generated statement true or is it merely grammatical?".

Disinformation: To see ABC's contribution to the problem of disinformation, consider the mechanics of a misleading prediction. In some cases, an AI model makes a prediction by combining concepts which ought-not be combined if they are to yield something truthful. An AI model queried to create a fake picture of a celebrity performing a controversial act, for example, might recall (pre-training) data about the likeness of a celebrity with data about unrelated people performing that controversial act, yielding an insidious form of disinformation: a deepfake.

In scientific literature, journalism, or law, a reader might easily spot such disinformation by consulting a written work's bibliography and considering whether original sources are relevant, reputable, and being synthesized properly into a novel insight. Not so with AI. Because of a lack of ABC, the end user viewing synthetic media has no source bibliography (and thus no ability to spot an AI prediction sourcing from such unqualified pre-training/RLHF/etc. data points, or to make adjustments to ensure the AI's prediction ignores/leverages data points appropriately). The AI user, for example, has no ability to say, "I queried this AI model for a picture of London, so why is it also sourcing from Hilton Hotels promotional materials instead of only photos of the English capital?". Consequently, an AI prediction can contain misleading information whose message is compelling but whose deceitful source is imperceptible to the viewer.

Proposed Remedies: Within the context of LLMs, recent work has attempted to address this through a myriad of methods such as, data cleaning, fine-tuning more data into AI models (e.g., RLHF, InstructGPT), direct oversight of deployed AI (e.g., HITL, auditing), measures of AI confidence (i.e., self checking), improving prompts (e.g., chain of thought, RAG), source attribution methods to reverse engineer the source-prediction relationship (i.e., influence functions), and others.

These efforts, however, face two fundamental limitations which prevent them from solving the issue. First, it has been shown that LLMs will always hallucinate because they cannot learn all computable functions between a computable LLM and a computable ground truth function (a proof which focuses on LLMs but requires no specific tie to language or transformers). And second, since AI will always hallucinate to some extent, the question is whether or not detection is possible and addressable. Since AIs only know how to output true facts based on the data they have consumed, this concerns measuring and controlling whether an AI model is sourcing from appropriate experts for each of its statements. That is, detecting disinformation, hallucinations, and other authenticity issues is not first a problem of intelligence, it's first a problem of attribution (and then perhaps a problem of intelligence).

However, as this thesis will soon show, when neural networks combine information through addition operations during training, they irreversibly compress the relationship between sources and predictions. No amount of post-training intervention (e.g. fine-tuning, auditing, influence functions, etc.) can fully restore these lost connections, solve the lack of ABC, and empower AI users to better avoid and address AI hallucinations, disinformation, or deepfakes. Yet, if attribution was solved, while it would still be possible to compel an AI to produce false information, it may become difficult (if not impossible) to do so without also revealing the inappropriate sources used to generate such false statements. Altogether, AI needs a bibliography.

Institutional Consequences

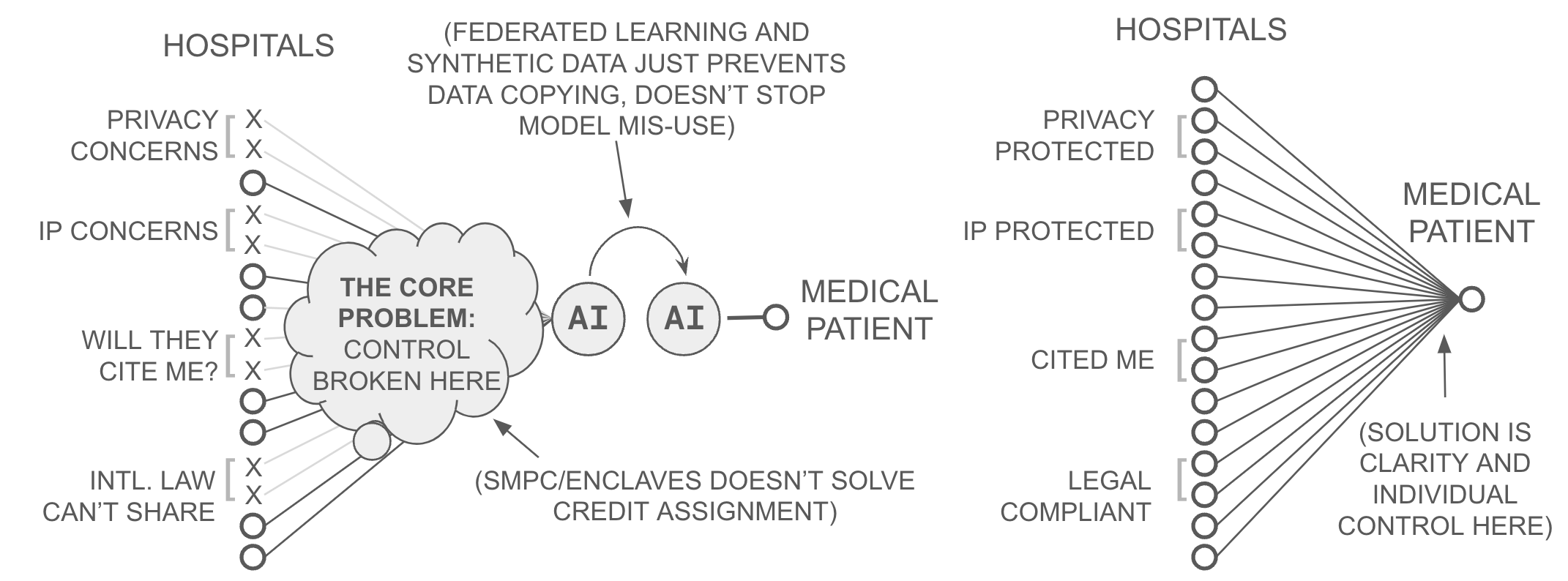

The lack of ABC creates a basic incentive problem at the institutional level. Data-owning institutions can either share data to create AI, or they can decline and maintain control over their data, a dilemma discussed publicly using words like copyright, privacy, transparency, and misuse. Leading cancer centers, for example, struggle to train AI to detect breast cancer using more than 3-4 million mammograms. Yet hundreds of millions of mammograms are produced annually worldwide.

This gap exists because medical facilities face an impossible decision: either withhold their data to protect patient privacy and maintain control (i.e. protect privacy, IP, security, legal risk, etc.), or share it and lose all ability to control how it's used. In 2023, multiple major medical centers explicitly cited this dilemma when declining to participate in AI research. Yet their complaint is not unique to medical information, it exists for any data owner who has some incentive to care about when and how their data is used.

The consequences of unmotivated data owners are staggering to consider. Despite AI drawing the attention of the world, even the most famous AI models have not inspired most of the world's data or compute owners to collectively act to train it. As described in chapter 2, 6 orders of magnitude more data, and 6 orders of magnitude more compute productivity remain untapped, such that even the most powerful AI models are trained on less than a millionth of the possible resources available.

Fighting Against Data and Compute for AI—Copyright, Siloing, and Rate-limiting: The resistance against AI training is widespread and highly vocal. It can be found regarding websites as big as Reddit, the New York Times, and Twitter, and as small as individual bloggers who are fighting against onerous scrapers. Resistance can be found across media and entertainment, but also in the siloing of the world's structured data. This resistance has cultivated a profound contradiction (unpacked in Chapter 2): the AI community feels there is a lack of data and compute (enough for NVIDIA chips to be in short supply and Ilya Sutzskever to announce "peak data") while around 1,000,000x more of each remains untapped.

Recent work has suggested that privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) can solve this collective action problem, suggesting technologies like federated learning, secure multi-party computation, and synthetic data. These efforts, however, face a fundamental limitation: they may enable data owners to retain control over the only copy of their information, but each of these technologies alone do not enable data owners to obtain fine-grained control over which AI predictions they wish to support. Consequently, none provide attribution-based control.

Federated learning and synthetic data, for example, avoid the need to share raw data, enabling them to retain control over that data, but they don't enable data providers to collectively control how an AI model they create is used because they do not provide a user-specific (i.e. attribution-based) control mechanism. Secure multi-party computation schemes (secure enclaves, SPDZ, etc.) might allow for joint control over an AI model, but they do not inherently provide the metadata or control necessary for data providers to add or withdraw their support for specific AI predictions (i.e. attribution). To use SMPC for ABC, one would need to re-train AI models whenever a part of an AI model's pre-training data needs to be removed (such as for compliance with right to be forgotten laws).

That is to say, unless AI models are continuously retrained, the SMPC problem is one of decision bundling (analogous to economic bundling), such that an entire group would need to decide whether to leverage an entire model... or not. Taken together, while some specific privacy concerns have been addressed by PETs, the broader incentive issues averting collective action have not. PETs offer collective production of AI models through encryption, but PETs do not offer fine-grained control by each contributing data source (i.e. attribution-based control)... because AI models don't reveal source attribution per prediction.

Yet, if attribution was solved in AI systems (in a more efficient manner than model retraining), it could be combined with techniques like FL or SMPC to provide ABC. Thus, the complementary challenge is attribution (i.e., the ability to enable each data participant to efficiently elect to support or not support specific AI predictions) without needing to relinquish or economically bundle control within AI models. This attribution task is also referred to as machine unlearning, which at the time of writing remains an open problem in the literature.

In chapter 2, this thesis reveals existing, overlooked remedies to attribution/unlearning, which enables chapter three to combine those ingredients with SMPC and related privacy enhancing technologies. Together, chapters 2 and 3 reveal existing, overlooked techniques for both attribution and control, revealing the AI community's viable (albeit presently overlooked) path to ABC, and a means to reverse incentives presently blocking 6+ orders of magnitude more data and compute productivity.

Societal Consequences

The lack of ABC creates a governance crisis unprecedented in scale at the societal level. This crisis manifests publicly as concerns about AI safety, value alignment, and algorithmic bias. Crisis arises because AI systems can derive their capabilities from millions of contributors yet remain controlled by whomever possesses a copy of an AI. This control structure sparks concern that either the AI or its owner will use the AI's intelligence in ways that conflict with society's values or interests. An LLM trained on chemistry research papers, for example, could be fine-tuned to generate instructions for bioweapons, with no way for the training data creators to prevent this misuse.

Recent work has proposed various oversight mechanisms and safety guidelines in response. However, these efforts face a limitation history has shown before: attempting to solve the problem of serving many by empowering few. When individuals, small groups, or tech companies train AI models on global internet data, decisions about content filtering and model behavior end up being made by AI models or small teams (at most thousands attempting to represent billions). AI governance therefore becomes an exercise in altruism, operating under the hope that AI models, IT staff, or institutions controlling them will forego selfish incentives to serve humanity's broader interests. These hopes may be disappointed: despite grand claims, leading AI labs may not be successfully evading their selfish incentives.

Attempted solutions to these problems remain insufficient because they don't address the underlying representative control problem. This problem stems from a fundamental decoupling: AI capability and AI alignment operate independently. Due to scaling laws, an AI model becomes more capable when its owner can centralize more data and compute. Yet its alignment with human values depends on the AI model and/or its supervisors choosing to forego selfish incentives, two forces that are not naturally correlated. This decoupling creates a dangerous asymmetry: unlike democratic systems, where a leader's power ideally scales with public support, AI systems concentrate power without requiring ongoing public consent. This asymmetry intensifies as AI becomes more capable, threatening democratic values through greater autonomy, adoption, and complexity.

This represents not merely a policy problem, but an architectural one rooted in how AI systems process information. As this thesis shows, when neural networks irreversibly: 1) combine data through addition operations and 2) decouple models from source data through copy operations, and 3) route the selection of trusted sources and users through ultra-high branching intermediaries, they sever the connection between data contributors and AI users, shifting control over an AI model to the model itself and/or its owner. This architectural design means no amount of after-the-fact regulation can restore the lost capability for continuous, granular, public consent over how AI systems use society's knowledge. The model remains controlled by whomever has a copy, and whomever has a copy (person or AI) may or may not elect to forego selfish incentives and serve the interests of society broadly. Society therefore faces a growing, collective need for representative control over AI systems, motivating a technical need for ABC within AI systems.

Yet, even if such AI-creating institutions could be made align-able to society, AI systems possess an even deeper flaw. An AI system's behavior is determined by its training data (first by pre-training data, then overridden in specific ways through RLHF/RLVF training updates). However, centralized institutions are gathering training data at a scale far greater than their ability to read and vet for data poisoning attacks. Consequently, as corporations, governments, and billions around the world consider relying upon AI systems (most especially agents) for information and decision making, they open themselves up to an uncomfortable fact: anyone could publish a few hundreds pages to the internet and change the behavior of their AI system in the future, likely in a way which is undetectable by AI companies.

As an early example of this, in 2011 the Huffington Post broke a story about the Hathaway Effect, that when famous actress Anne Hathaway experiences a significant career moment, similarly-named Berkshire Hathaway stock rises as a result of algorithmic agents failing to disambiguate in online sentiment analysis. The setup is a direct comparison to LLMs. These stock agents crawl the web looking for content, aggregating sentiment about companies (and their products, services, management teams, etc.), and translate these indicators into stock signals used for training at major financial institutions. However, while the internet contains useful signal for trading stocks, it also presents itself as a wide-open funnel for noise. And through sheer chance, Anne Hathaway's last name provides the accidental noise some early AI agents can fall for.

And while this somewhat humorous societal phenomena is perhaps harmless, it is a very real example of a more disturbing societal risk for modern AI agents. In a very real sense, as web-trained AI agents make their way into government agencies, job application portals, healthcare systems, financial models, security/surveillance systems, customer service portals, credit rating models, they are all making their decision making process available for anyone in the world to edit, simply by uploading a webpage with the right type of data poisoning content, and making that webpage available to the right web crawlers. Consequently, even if centralized AI companies were altruistic, the data they rely upon for intelligence need not be. The simultaneous problems of poisonous data and non-altruistic intermediaries provides technical motivation which goes beyond mere representative control; to solve these problems, society needs representative control which can be source-weighted for veracity in a specific context, attribution-based control in AI systems.

Geopolitical Consequences

The lack of ABC creates tension between AI capability and democratic values at the geopolitical level. AI systems become more powerful with more data and compute, as described by so-called "Scaling Laws" and implied by the "Bitter Lesson". But without ABC, acquiring data (and compute) means acquiring a copy of it within a company, and acquiring a copy means centralizing unilateral control... over the data, over the compute, and over the AI systems this centralization creates.

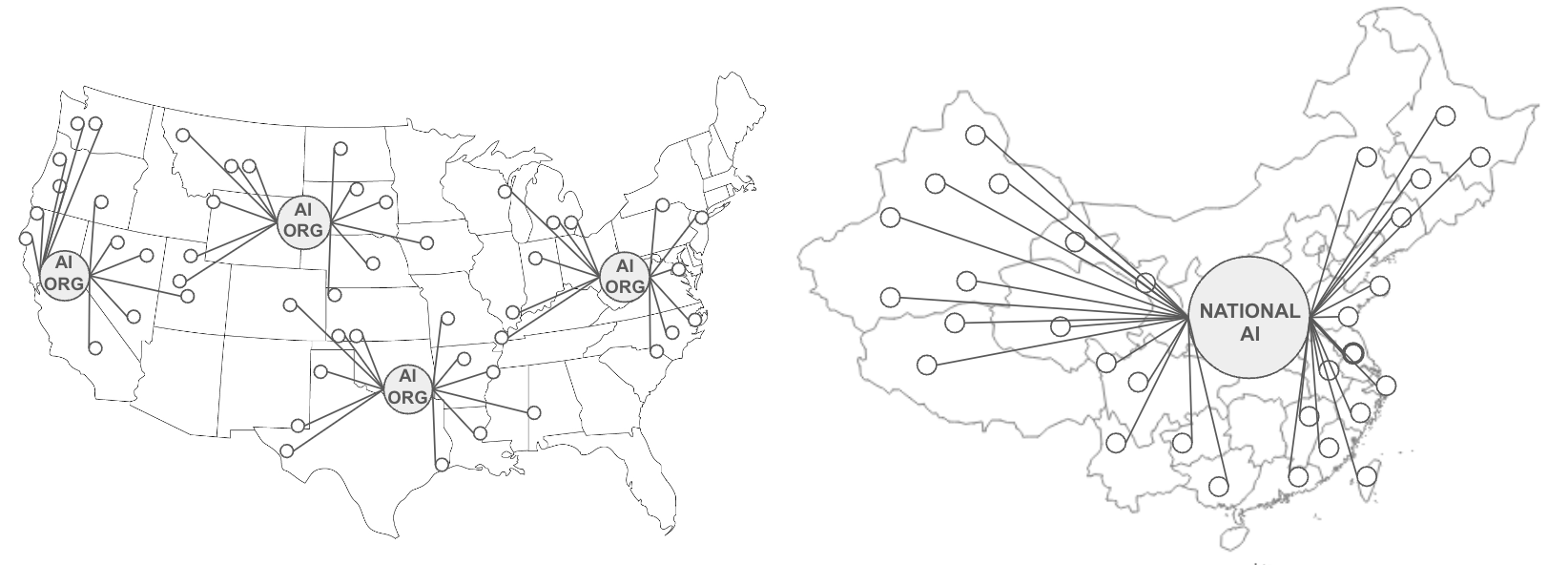

This dilemma constrains democratic nations to two normative paths. Corporate AI caps AI capability at whatever data and compute companies can acquire (e.g. Google, Meta, X, etc.). National AI caps AI capability at whatever data and compute nations can centralize (e.g., China). Democratic nations face this tension most clearly in situations like the US-China AI competition: they must either compromise their principles by centralizing data and compute, or cede AI leadership to autocratic nations who face no such constraints.

Some policymakers have responded to this crisis not by addressing the underlying ABC problem, but by proposing a "Manhattan Project" for AI. These proposals suggest competing with China's centralization by out-centralizing them... meeting authoritarian AI capability by building a larger, even more centralized AI capability domestically.

Such an approach would face multiple challenges. To win, it would require overlooking democratic principles (e.g., privacy, personal property, freedom of choice, etc.) to centralize AI-powered decision making in a single, maximally-powerful, state-sponsored AI. It would still face uncertainty about exceeding China's AI capability; while the US may have a head-start on compute and talent availability, China has a 4x larger population from which to draw data.

Yet this dilemma only exists because of the lack of ABC. With ABC, vast swaths of data providers could collectively create individual AI predictions. And with ABC, AI users could request which data sources they wish to use for their specific AI predictions. ABC would subvert the need to centralize data, compute, and talent by creating a third AI paradigm beyond corporate AI or national AI... AI as powerful as the amount of data, compute, and talent across the global free market. For now, however, emerging ABC remains largely unrecognized, while policymakers consider the centralization of data and AI-powered decision making at an unprecedented scale.

Centralization Consequences

At its core, AI intermediates a flow of information from billions of people (i.e. training data sources) to billions of people (i.e. AI users). However, the lack of ABC in AI systems obfuscates this underlying communication paradigm and presents AI as a tool of central decision making. Yes, AI systems promise to process humanity's knowledge at unprecedented scale. Yet their very architecture forces central AI creators to first accumulate that knowledge (even for "open-source" AI), then guide how society accesses and uses it. Rather than enabling direct communication between those who have knowledge and those who seek it, AI systems become intermediaries that extract knowledge from many to serve the interests of few (albeit by guiding the decisions of many). It reminds one of the rise of the mainframe computer in the 1950s and 60s, which obfuscated computing's forthcoming dominant use as a communication technology (i.e. the internet), presenting computing instead as a centralized coordination apparatus.

In AI, this architectural obfuscation creates stark dilemmas. Users must trust central authorities about what sources inform AI outputs. Data owners must choose between sharing knowledge and maintaining control over how it's used, starving AI of all but 0.0001% of the world's data. Society must accept governance by tiny groups over systems trained on global knowledge. And democracies must either embrace centralized control over data, compute, and AI-powered decision-making or cede AI leadership to nations who do. Each of these dilemmas stems from the same technical limitation: AI systems which fail to enable AI users and data sources to control when and how AI is used... ceding that power to central AI creators instead.

Yet these challenges also reveal an opportunity. By reformulating how AI systems process information (shifting from operations that break ABC to ones that preserve it) society is actively overcoming the perception of AI as a tool of central intelligence, revealing it to be a communication paradigm of great magnitude. And as described above, this change will not just solve technical problems; it could realign AI development with democratic values. The path to this transformation begins with the mathematical operations which preserve or destroy ABC in AI.

Underlying Causes and Contributing Factors

Cause: Attribution and The Addition Problem

When a person concatenates two numbers together, they preserve the integrity of each contributing piece of information. However, when a person adds two numbers together, they produce a result which loses knowledge of the original values, and thus also loses the ability to precisely remove one of those values later. Consider the following example:

Concatenation preserves sources and enables removal:

"1" + "6" = "16" (can identify and remove either "1" or "6")

"2" + "5" = "25" (can identify and remove either "2" or "5")

Addition erases them:

1 + 6 = 7 (cannot identify and then remove either input)

2 + 5 = 7 (cannot identify and then remove either input)

In the example above, receiving the number "7" provides no information on what numbers were used to create it, while receiving the number "16" preserves the numbers used to create it.

In the same way, when a deep learning AI model is trained, each datapoint is translated into a "gradient update" which is added into the previous weights of the model, losing the ability to know which aspects of each weight were derived from which datapoints and thus the ability to later remove specific datapoints' influence. Thus, despite recent work, when an AI model makes a prediction, no-one can verify which source datapoints are informing that prediction (i.e. influence functions), nor can they cleanly remove problematic datapoints' influence (i.e. "unlearning") without retraining the entire model. Despite attempts, influence function based unlearning remains an unsolved challenge, blocking an ABC solution... because addition fundamentally destroys information which cannot then be recovered. Addition blocks attribution, which blocks attribution-based control in AI systems.

Cause: Control and The Copy Problem

When a person makes a copy of their information and gives it to another, they lose the ability to enforce how that information might be used. And upon this core flaw, even if AI attribution was solved (e.g. unlearning and influence functions were solved), certain dominoes would still fall and avert ABC within AI systems.

To begin, consider that when training data providers give a copy of their training data to an AI organization, they lose the ability to control how that data might be used, thereby losing any enforceable control over how the resulting model might be used. Similarly, if one gives an AI model to someone else, the former loses the ability to control how that model would be used. Taken together, because of the overuse of copying, AI is unilaterally controlled by whomever has a copy of the trained model. At a minimum, this always includes the organization responsible for its training (i.e. "closed source AI"). In the maximum, this includes any person who downloads a model from the internet (i.e., "open source AI").

While many debate the merits of so-called "closed source" or "open source" AI models, the copy problem underpins a constructive criticism of both: both are systems of unilateral control because of the over-use of copying. And the over-use of copying doesn't just create systems which can be unilaterally controlled, it creates systems which must be unilaterally controlled... systems which explicitly prohibit collective control. Taken together, addition blocks attribution, copying blocks collective control, and together these foundational flaws block attribution-based control in AI systems.

Cause: Bi-directional Delegation and The Branching Problem

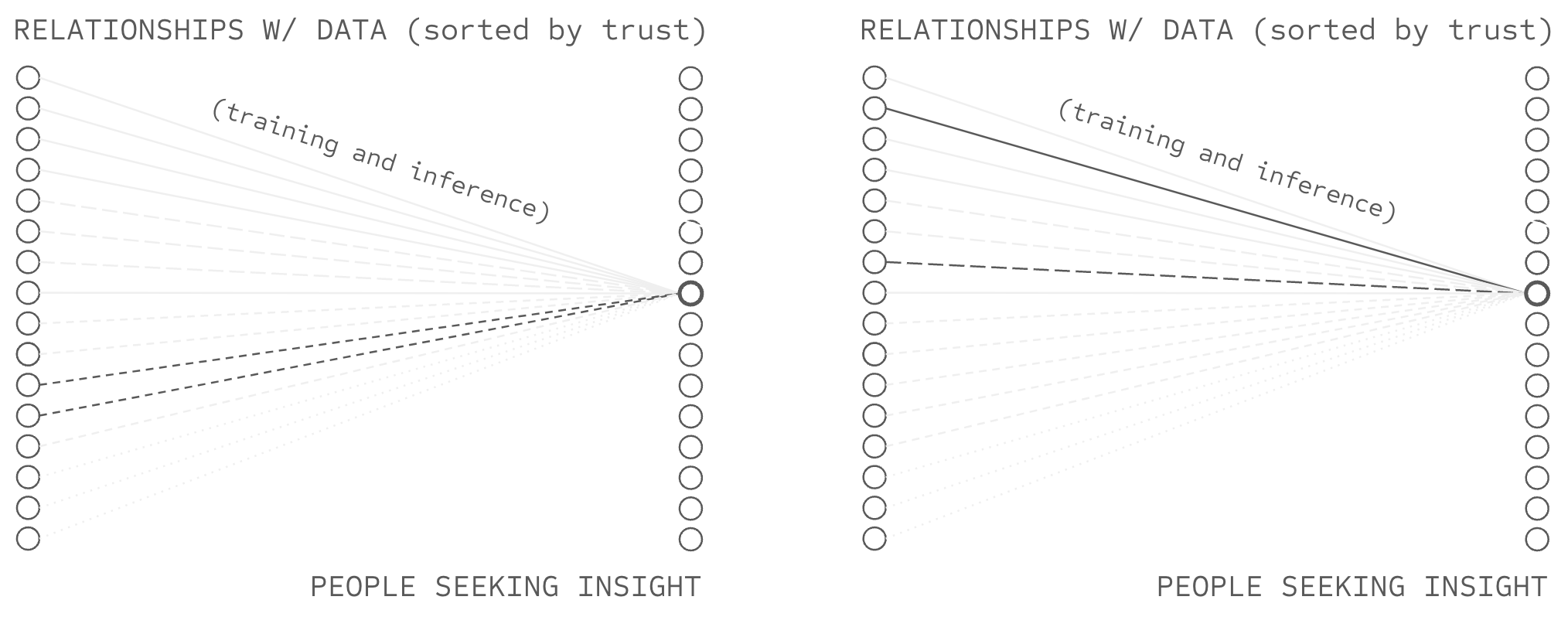

When a person needs to synthesize information from a small number of sources, they can often leverage their existing trust networks (people, brands, and various groups or institutions they are familiar with) to obtain high-veracity information they trust. Similarly, when a person needs to broadcast information to a small number of recipients, they can often evaluate each recipient's trustworthiness before sharing, and in-so-doing protect their privacy, further their interests, and broadly avert what they might consider to be information mis-use. However, when a person needs to synthesize information from billions of sources or broadcast to billions of recipients, they necessarily cannot evaluate each party individually; they are forced to delegate evaluation to intermediaries who scale trust evaluation on their behalf. And upon this core constraint, even if AI attribution was solved (e.g., unlearning and influence functions were solved) and collective control was solved (e.g. the copy problem), certain dominoes would still fall and avert ABC within AI systems.

To begin, consider that when sources contribute training data to high-branching AI systems (where billions of sources branch into a single model), they lose the ability to evaluate which of billions of users will leverage their contribution... thereby losing any enforceable control over whether those users are trustworthy or align with their values. Similarly, when users query high-branching AI systems (where a single model branches out to billions of users), they lose the ability to evaluate which of billions of sources inform their predictions... thereby losing any enforceable control over whether those sources are reliable, independent, or free from conflicts of interest. Taken together, because of the overuse of high-branching aggregation, AI concentrates source and user selection at whichever entities facilitate high-branching operations: the platforms connecting billions of sources to billions of users.

While platforms may attempt to perform this selection faithfully, the branching problem underpins a structural limitation: high-branching operations mathematically necessitate centralized selection authority at information bottlenecks. And the overuse of high-branching aggregation doesn't just create systems which can have centralized selection, it creates systems which must have centralized selection, systems which explicitly prohibit distributed bilateral authority over source and user selection. Taken together, addition blocks attribution, copying blocks collective control, and high-branching blocks distributed selection. Taken together, addition, branching, and copying avert attribution-based control in AI systems.

Contributing Factors: Consensus and the Natural Problem

Yet technical barriers alone may not explain ABC's absence. Perhaps surprisingly, this thesis will describe how the technical ingredients for an ABC solution already operate at scale in specific AI contexts. This disconnect between possibility and adoption demands explanation.

Consider the incentives: democratic nations seek to compete with authoritarian AI programs, data owners want to maximize revenue, and societies aim to enhance AI capabilities while ensuring those capabilities benefit society broadly. ABC could advance all these goals, and, as this thesis surveys, local incentives have inspired local solutions to emerge and become tested at scale. Yet ABC remains conspicuously absent from mainstream AI development. Why?

While a complete sociological analysis is beyond the technical scope of this thesis, examining current AI development reveals a striking pattern: researchers consistently draw inspiration from a specific conception of biological cognition, cognition that provides no attribution-based control over its predictions. For example, humans do not ask permission from their parents, friends, co-workers, or evolutionary ancestors every time they seek to use a concept taught to them by these external parties (i.e. every time they open their mouth or move their body... all actions learned at some point from another party). For those who see AI development as fundamentally about imitating this meme of biological cognition, ABC represents a deviation from nature's blueprint.

Moreover, ABC may threaten established business models. Large AI companies have built multi-billion (soon, multi-trillion?) dollar valuations in part on their ability to use training data without compensating providers, and to bend the behavior of AI models in a way that suits them. For example, the targeted advertising industry, projected to reach over a trillion dollars by 2030, relies heavily on AI systems that obscure rather than expose the sources influencing their recommendations, and enable the AI owner to sell influence over the model to the highest bidder (e.g. ads in newsfeed algorithms). An AI deployment with true ABC might disrupt both of these profitable arrangements, arrangements which are the primary business models of several of the largest AI developers.

This relationship to ABC reflects a deeper tension in AI development: the choice between transparency and mystique. In the case that ABC provides precise, controllable, and attributable intelligence, many influential voices may prefer the allure and profitability of black-box systems that more closely mirror a specific conception of biological cognition. Yet, this dichotomy does not just shape technical decisions, but who retains power over AI, and the future of AI's role in society. As readers proceed through this thesis, they might consider: what if this preference for black-box AI systems stems not from technical necessity, from safety maximization, or from economic/political incentive, but from deeply held assumptions about what artificial intelligence should be? For now, the thesis will overlook such concerns, returning to them in closing notes.

Thesis Outline

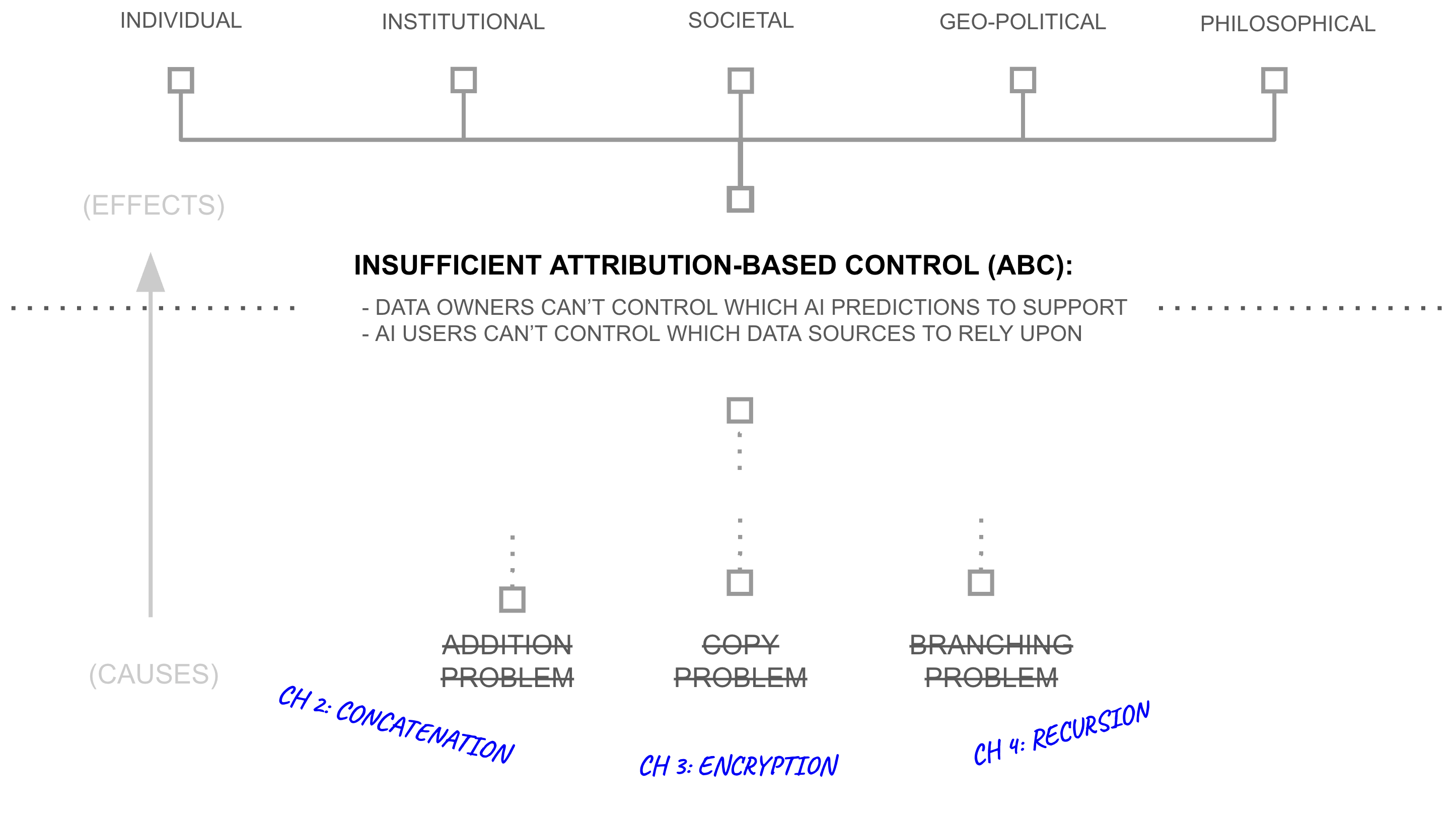

Across three chapters, this thesis progressively constructs a new paradigm for AI development and deployment by describing how breakthroughs in deep learning, distributed systems, and cryptography might: avert the addition, branching, and copy problems, provide a means for AI systems with attribution-based control, and better align AI with free and democratic society.

Chapter 2: Addition—From Deep Learning to Deep Voting

The thesis begins at the mathematical center of modern AI, artificial neural networks. Chapter 2 reveals how reliance on addition operations in deep learning averts attribution and promotes centralized control into AI systems.

Chapter 2 surveys recent developments in sparse deep learning architectures and cryptographic protocols that displace some addition operations with concatenation operations. The chapter describes how these architectural modifications preserve mappings between training examples and their influence on specific predictions, a property that standard neural networks lose through parameter addition and dense inference. The chapter formalizes these architectures as deep voting: ensemble methods where model components trained on disjoint data subsets (and which remain in a concatenated state after training) only merge through addition during inference in a more linear fashion, and perform that merge in a way which is bounded by intelligence budgets. In this way, it describes how recent work in deep learning sparsity and cryptography can be combined to control source-prediction influence in deep learning systems.

The chapter then documents empirical results demonstrating that deep voting architectures achieve comparable accuracy to standard deep learning while maintaining per-source attribution. This property enables two capabilities unavailable in addition-based architectures: users can specify weights over training sources after training (dynamic source selection), and sources can withdraw their contributions from specific predictions (selective unlearning). These results establish that AI attribution (maintaining verifiable mappings from predictions back to contributing training sources) is architecturally feasible at scale, addressing a necessary requirement for attribution-based control in AI systems.

Chapter 3: Copying—From Deep Voting to Network-source AI

While Chapter 2 synthesizes techniques for AI with attribution, it surfaces a deeper challenge: how can we enable selective sharing of information without losing control through copying? Chapter 3 surveys recent cryptographic breakthroughs and reframes them in an end-to-end framework: structured transparency, describing how combinations of cryptographic algorithms can allow data owners to collectively enable some uses of their data without enabling other uses.

When applied to the attribution-preserving networks from Chapter 2, structured transparency enables a new kind of AI system, one where predictive power flows freely through society without requiring centralized data collection. Data owners can contribute to collective intelligence while maintaining strict control over which predictions their information is used to support, seemingly fulfilling the technical requirements for attribution-based control (ABC) in AI systems.

Chapter 4: Branching—From Network-Src AI to Broad Listening

Chapters 2 and 3 provide the technical foundation for ABC in AI, enabling data sources to calibrate who they wish to imbue with predictive power, and enabling AI users to calibrate who they trust to provide them with value-aligned predictive power. However, given the billions of people in the world, a new problem arises: how can data sources or AI users know who to trust?

The Scale Problem

ABC requires distributed authority over billions of potential sources, but humans can sustain high-trust relationships with approximately 150 entities (i.e., Dunbar's Number). This creates a gap of seven orders of magnitude between what ABC requires (~109 sources) and what individuals can evaluate (~102 relationships). Delegation becomes architecturally necessary, but which delegation architecture preserves ABC's requirement for distributed authority?

The Dunbar Gap

Consider your close friends (people you'd call if you needed help moving or advise about a major life decision). Most people sustain perhaps a dozen such relationships. Expand to include colleagues you genuinely know (not just recognize), neighbors you actually talk to, family you stay in touch with, (etc.). Dunbar suggests this number caps around 150.

Now consider what ABC requires: evaluating which of billions of potential sources to trust, which queries to allow, or which contexts are appropriate. The gap isn't close, its seven orders of magnitude off. It's not like needing to manage 200 relationships when you can handle 150. It's needing to manage billions when you can handle hundreds.

Asking individuals to directly evaluate trust at ABC's required scale is like asking someone to maintain close friendships with every person in China (not theoretically impossible, just absurdly incompatible with how human relationships actually work).

1st Criterion: Maximizing Breadth

To address this scale problem while preserving ABC's distributed authority, Chapter 4 identifies two criteria that any delegation architecture must satisfy. The first is the breadth criterion. Truth-finding requires aggregating from many independent sources because coordinated deception becomes logistically harder when information must be consistent across many independently-weighted witnesses. However, filtering through centralized bottlenecks reduces this advantage. If all sources must pass through a single institution, coordination difficulty decreases since fewer parties must align their story to coordinate a compelling deception.

2nd Criterion: Maximizing Depth

The second criterion is the depth criterion. Trust evaluation requires sustained relationships that enable: observing behavior over repeated interactions, understanding context to verify independence, experiencing consequences through social closure, and maintaining accountability through ongoing reciprocity. This cannot be achieved through weak ties or at web-scale per evaluator; trust assessment requires strong ties maintained within bounded relationship capacity.

The Conflict Between Breadth/Depth and Dunbar's Number

These criteria are in direct conflict. The breadth criterion would be maximized by aggregating from billions of sources to make coordination difficult, while the depth criterion would be maximized by only trusting parties with whom one has spent great deals of time developing a high-trust relationship (approximately 150 sustained relationships according to Dunbar).

One might surmise that the only possible solution to this conflict is delegation, to maintain 150 strong relationships with parties who possess the scale to create relationships with billions of entities in the world: web-scale institutions. However, such a high-branching social graph (high branching in two places, as such institutions accept information from billions of sources and provide services to billions of recipients) violates the definition of attribution-based control.

When individuals connect to institutions and institutions connect to billions of sources, all information flow passes through institutional nodes that occupy structural holes... positions controlling information flow between otherwise disconnected parties. This bottleneck structure violates the depth criterion through multiple mechanisms: monitoring costs prevent institutional evaluation of independence across billions of source pairs, relationships between institutions themselves and their sources become weak ties at scale (e.g., problems within Trust and Safety in online platforms, Sybil attacks, and Spam) as fixed institutional resources divide across billions of sources, social closure disappears due to negligible network overlap between sources at billion scale, and institutions necessarily control source selection from their bottleneck positions. The architectural bottleneck thus concentrates authority over source selection at institutional nodes, violating ABC's requirement for distributed authority regardless of institutional intentions or policies. Taken together, high-branching social institutions are unfit to offer ABC in AI systems.

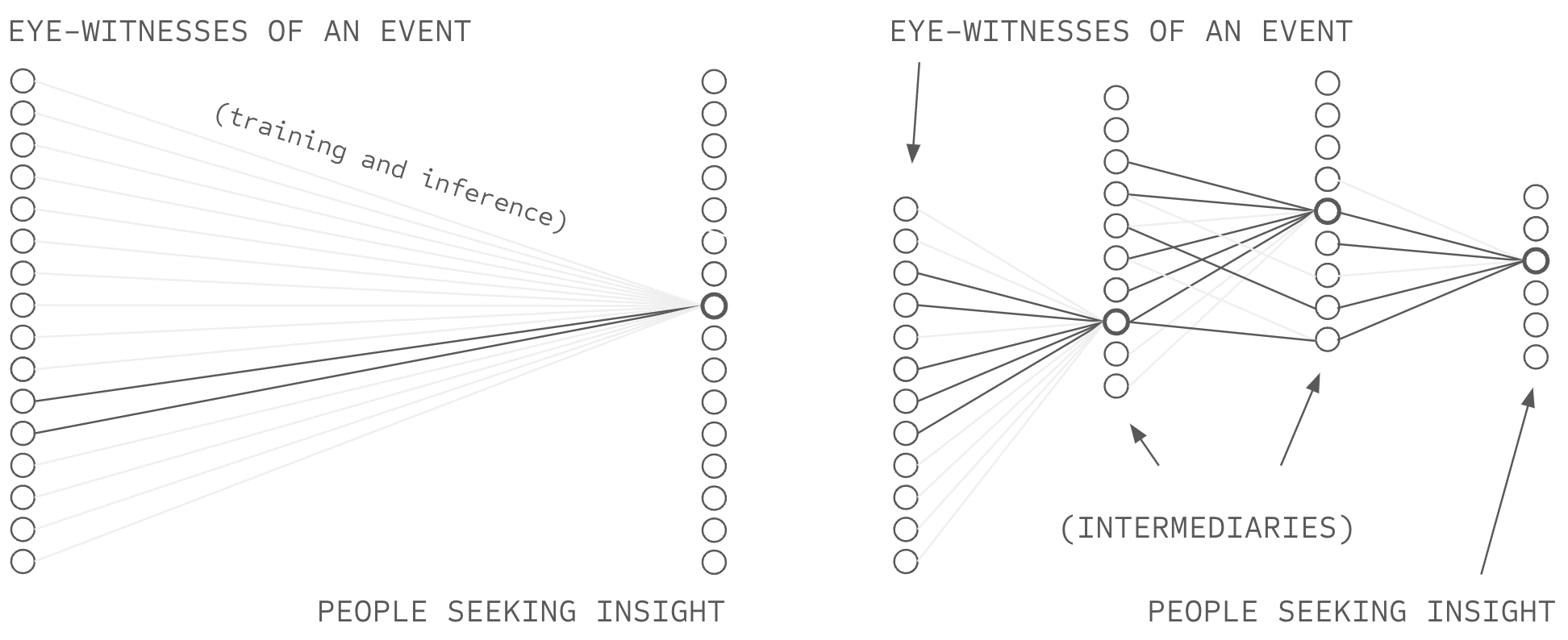

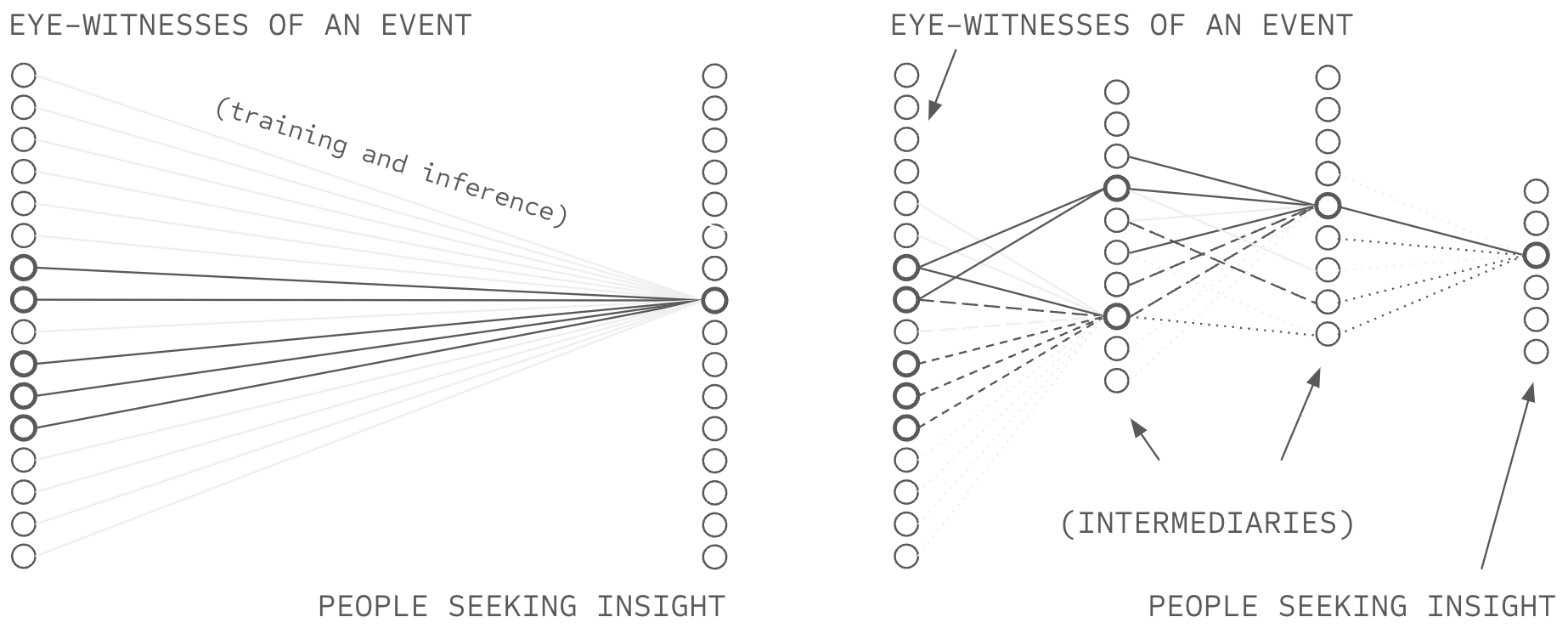

The Solution: Low-Branching Recursive Delegation

Chapter 4 proposes low-branching recursive delegation as an alternative architecture that satisfies both criteria by achieving exponential reach, propagating trust recursively over H hops. For example, if H=6 (e.g. six degrees of separation), this approach would achieve exponential reach of 506 = 15.6 billion sources.

This pattern has precedent in systems achieving billion-scale reach with distributed authority: PageRank (pages link to ~10-100 pages, authority distributes to authors), academic citations (papers cite ~10-50 sources, authority distributes to researchers), PGP web of trust (users sign ~10-50 keys, authority distributes to users), and Wikipedia (articles cite ~10-50 sources, authority distributes to editors).

This massive path redundancy eliminates bottlenecks. No single party controls access to sources, and users can route around failing or captured intermediaries through alternative verified paths. The architecture simultaneously satisfies the depth criterion by constraining each participant to approximately 50 connections (k = 50 < 150), preserving capacity for strong ties with sustained evaluation, verification of independence across manageable pairs, and social closure through network overlap.

Because verification occurs at each hop rather than concentrating at institutional nodes, the quality of trust evaluation remains high throughout the recursive chain. Each person evaluates their 50 connections through sustained relationships, and those connections evaluate their 50 through sustained relationships, creating verified paths from users to billions of ultimate sources.

Chapter 4 formalizes this architecture for ABC by integrating recursive trust propagation with intelligence budgets from Chapter 2 and privacy-preserving structured transparency from Chapter 3. The result: each person can synthesize information from billions of sources, weighted through local trust relationships, and verified at each hop, transforming network-source AI's raw listening capacity into trust-weighted "word-of-mouth at global scale." Taken together, they provide a viable path towards attribution-based control in AI systems.

Chapter 5: Conclusion—AI as a Communication Tool

Chapter 5 returns to examine how the technical developments in Chapters 2-4 address the cascading consequences of missing ABC laid out in this introduction. It demonstrates how concatenation-based networks solve the addition problem by preserving source attribution, how encrypted computation solves the copy problem by enabling sharing without loss of control, and how recursion solves the branching problem by enabling a digital word-of-mouth at scale through AI systems.

The chapter then analyzes how these capabilities fundamentally transform the nature of artificial intelligence. When AI relies on addition, copying, and branching it necessarily becomes a tool of central control, forcing us to trust whoever possesses a copy of the model. But as AI comes to preserve ABC, it enables something radically different: a communication tool that connects those who have knowledge with those who seek insights. Beyond a technical shift, ABC actively re-frames AI from a system that produces intelligence through centralization into a system that enables intelligence to flow freely through society.

The chapter concludes by arguing that democratic societies face an architectural choice that will determine the future of AI: continue building systems that mathematically require central control, or embrace AI architectures that enable broad listening. It demonstrates why broad listening uniquely addresses the individual problems of hallucination and disinformation through source verification, the institutional problems of data sharing through aligned contributor incentives, the societal problems of governance through continuous public consent, and the geopolitical challenge of competing with authoritarian AI by harnessing the collective resources of the free market. Taken together, the chapter argues that ABC isn't just technically possible, it's essential for transforming AI from a technology that advantages central control into one that advantages democratic values. The future of AI need not be a race to centralize. Through broad listening, it can become a race to connect through AI systems with attribution-based control.

References

- (2022). On the Origin of Hallucinations in Conversational Models: Is it the Datasets or the Models? Proceedings of NAACL 2022, 5271–5285.

- (2020). Deepfakes and Disinformation: Exploring the Impact of Synthetic Political Video on Deception, Uncertainty, and Trust in News. Social Media + Society, 6(1).

- (2023). ChatGPT Hallucinates when Attributing Answers. SIGIR-AP '23, 46–51.

- (2023). Learning to Fake It: Limited Responses and Fabricated References Provided by ChatGPT for Medical Questions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Digital Health, 1(3), 226–234.

- (2024). Hallucination is Inevitable: An Innate Limitation of Large Language Models. arXiv:2401.11817.

- (2024). Mechanistic Understanding and Mitigation of Language Model Non-Factual Hallucinations. Findings of EMNLP 2024, 7943–7956.

- (2020). Beyond Privacy Trade-offs with Structured Transparency. arXiv:2012.08347.

- (2023). Organizational Factors in Clinical Data Sharing for Artificial Intelligence in Health Care. JAMA Network Open, 6, e2348422.

- (2016). Federated Learning of Deep Networks using Model Averaging. arXiv:1602.05629.

- (2020). The future of digital health with federated learning. npj Digital Medicine, 3(1).

- (2024). A Survey of Machine Unlearning. arXiv:2209.02299.

- (2016). Concrete Problems in AI Safety. arXiv:1606.06565.

- (2020). Artificial intelligence, values, and alignment. Minds and Machines, 30(3), 411–437.

- (2020). Bias in data-driven artificial intelligence systems—An introductory survey. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 10(3), e1356.

- (2020). Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. arXiv:2001.08361.

- (2022). Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models. arXiv:2203.15556.

- (2019). The Bitter Lesson. Incomplete Ideas (blog).

- (2016). Deep Learning. MIT Press.

- (1993). Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16(4), 681–735.

- (1977). A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry, 35–41.

- (2024). The Ethics of Advanced AI Assistants. arXiv:2404.16244.

- (2023). The Operational Risks of AI in Large-Scale Biological Attacks: A Red-Team Approach. RAND Corporation.